|

America is a nation of unending highways, millions of automobiles and people on the move. An intrinsic part of this ballad of the road is the ubiquitous convenience store, that small patch of light in a sea of darkness, a moment of respite for the weary traveler. That foam cup of black coffee, that donut is never more welcome or rejuvenating.

Over the years the arteries of these stores have spread from the wilderness and small towns to suburbia, to the urban jungle of big cities, to the streets and the lobbies of skyscrapers. Since they are open 24 hours 7 days a week, they are a small oasis for the road weary and also for the 8 hour shift work warriors who have simply forgotten to buy bread or need their quick fix of a lottery ticket. Increasingly, you can safely bet that the person who hands you your change or your cup of coffee is South Asian. The National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS) estimates there are over 140,655 convenience stores in the United States with annual sales of $495 billion. This half-trillion-dollar retail channel comprises of many small entrepreneurs, besides the well-known multi-state and nationwide chains, such as 7-Eleven. While there are no tabulated figures for South Asians, industry watchers estimate the number of South Asian owned stores nationwide between 50,000 to 70,000, almost a third to half of the total. Satya Shaw, president of Asian American Convenience Store Association, (AACSA) which was formed in 2005, estimates there are about 70,000 South Asian owned stores, raking in over $100 billion in revenues. According to Tariq Khan, chairman of the National Coalition of Associations of 7-Eleven Franchisees, the largest convenience store chain in the country, more than 50 percent of the chain’s franchised stores are owned by South Asians. Of the 1,200 7-Eleven stores in California alone, at least 600-700 are owned by South Asians.

“We are definitely even a larger number than the Asian American motel ownership,” says Khan about the convenience store industry. In his 25 years of traveling across the continent for 7-Eleven related business, he has met thousands of C-store owners, both in various franchises as well as independent stores. He says, “Today, if you travel across the country, you will not go 30 miles without seeing owners who look like us.” The convenience store industry continues to be dominated by small, independent operators, who typically own and operate a single store. According to NACS, nearly 60 percent of all stores in the United States are independently owned. At the other end of the scale, stores owned and operated by chains owning 500 or more stores account for some 13 percent of all convenience stores. The majority of South Asian owners seem to lease or own independent stores. Says Shaw of AACSA, “Just as initially the motel owners went for independent properties rather than franchises, 60 percent of the Indian owned stores are independent, non-franchise stores.” Why are South Asians in the C-store business in such massive numbers? “Retail is an occupation held in highest esteem in many other countries, so naturally retail is a preferred channel for many new Americans,” says Michael Davis vice president for Retailer Services, NACS. “Retail also is an occupation that can easily transfer among borders, cultures and languages. The convenience store industry also offers affordable entry points.” South Asian immigrants have long played a role from working in C-stores, to managing them, leasing them and increasingly owning them. These stores have become the building blocks of a comfortable livelihood in America, and the road to success is often paved with Slurpees. “I really think we are the backbone of the industry. With all the bankruptcies in the 90’s of convenience stores, I think Indians and Pakistanis are the reason the companies survived, because we came in and bought those stores,” says Khan, who migrated to the United States from Pakistan in the 1970s. “All those stores went belly up in the Midwest and when they were gobbled up, they were gobbled up by people like myself.”

The classic example of the business savvy and chutzpah in the C-store business is H.R. Shah, who came to the United States in the 1970s from a poor rural family in the village of Bahadarpur, where even with a college degree, he could not find a job. Life was hard, or as he colorfully puts it, “It was kabhi khushi kabhi gaam.” After arriving in the United States, he worked at a friend’s grocery store where he learnt the business. Later he became a commercial real estate broker, helping immigrant clients find retail stores. Over a decade, he learnt the ropes of the business and built up profiles of thousands of Indian buyers in the tri-state area. One day the Krauszer’s chain, one of the oldest in the country, came up for sale. Started in 1910, it had fallen on hard times and its 300 stores were facing bankruptcy. Shah, who by now knew the convenience store business well, bid on the stores and acquired them for 30 cents on the dollar. He says with satisfaction, “I was the first Indian to own a convenience store chain and I managed to save the jobs of 1,300 employees.” Since he had a ready list of Indian and Pakistani potential buyers, he sold most of the stores, keeping just a few in his company, National Food Stores. Many stores were sold to existing managers, turning them into owners while he kept the rights to the Krauszer’s name. He added additional stores in Connecticut, Maryland and Pennsylvania to expand the chain to 400 stores.

Shah credits his good fortune to the day he bought the Krauszer’s chain, “That was the turning point in my career.” He recalls that many of the South Asian store owners he sold to now have five, even ten stores today. So why do desis tend to gravitate to the C-store business? “In this business you don’t need experience – the prices are on the merchandise. You don’t even have to know much English. You can get by with ‘Good morning’ and ‘Thank You’ and ‘Have a nice day,'” he says. “This business is also recession proof, because every morning people need the newspaper, bread, milk, coffee and cigarettes. If they don’t have a job, they’re likely to be still drinking coffee, perhaps having more cigarettes and certainly reading the newspaper.” He jokes that while the hours are long, C-store owners save even more by not having the time to party: “So it’s saving, saving and more saving. Seven days a week, you work 12 hours a day and with those savings you can buy another store.” Another major player is Raj Vakharia, who is partner in the 280-store Uni-Mart, a leading convenience store and gasoline station chain in Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware and Maryland. The Company also operates discount tobacco stores under the name “Choice,” and two-thirds of its locations also sell gasoline. Recently the company was in the news after several store owners sued for fraud and breach of contract, claiming they were misled about operating costs and profitability. For long, the only South Asian on TV was Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, the owner of the Quik-E-Mart in the TV show The Simpsons. He is known for having worked for 96 hours straight, taken so many bullets that bullets ricochet off the bullets already lodged in his body! He is savvy, brainy and a one-man dynamo of energy. And a Ph.D to boot. The stereotype has a sliver of truth, as hard work, family solidarity and resourcefulness are at the root of South Asian success in the C-store business. Many owners have professional degrees and include some physicians. Dinesh Gandhi, of Tampa, Fl., owns two C-stores and two hotel properties, besides six other stores where he is partner. All his stores are non-franchise with names like Kamala Food Stores, named after his mother, and A and Z Discount Beverages. All have Citco Gas stations attached to them. Like many successful entrepreneurs, his initial days were rough. Gandhi, who came as a student from Navsari in Gujarat, worked part-time in the motel industry and then in a convenience store before finally buying it. Was it difficult? “Yes and no. Rome wasn’t built in a day,” he says. “It’s always tough to start. Being a newcomer, it’s hard getting financing and also help in the store.”

So it’s something quite wonderful, considering you can start from nothing and get to where you have? “Absolutely,” says Gandhi. “That’s the beauty of this country. We worked so hard – 16 hours a day, seven days a week. Also we get help from the friends and family. The loan process in this country is not as hard as in India. Once you work hard, you can grow faster.” Gandhi, president of the Gujarati Samaj and founder member of AACSA, ruminates about the ups and downs of the C-store business. “Right now you can call it as the fun part, but it was really tough in the beginning. You came with empty hands. You had no contacts and very little money. But you triumph over the obstacles, such as collecting the money, manpower, running the store with little money – so you go day by day. It’s a big opportunity and you don’t want to lose that opportunity, but you have so little money. “My wife and my brother were helping me and we were working round the clock. Americans work 40 hours; we hardly slept 40 hours a week! There were so many different jobs to do. As one man running the store you are working as a cashier, as janitorial guy, you are also doing the ordering and the banking.

“In the evening you fill up the cooler, mop and clean the restroom. We would hardly sleep till midnight and we would have to get up at 5 am. So it’s not a fun job. As they say in Hindi, ‘dukh ke din nahin par bahut sankat ke din the. (They were not days of sorrow, but days of great difficulties.) Your goal is to grow fast and have your own store. You borrow the money and you want to return it fast.” His story is repeated by almost every South Asian entrepreneur on both coasts. Bipin Patel, president of Speedy Mart Development Inc., in Springfield, N.J., has a tough-time story he can relate. When he came from Nadiad, a small city in Gujarat in 1984, the future looked bleak. He had married a green card holder and for the first few years he worked in small stores. Since his wife’s family worked in manufacturing, they had no contacts in the C-store business. He recalls, “I didn’t have any godfather to guide me. I had to get used to this whole business and I didn’t have any experience. It was difficult to even run the cash register because I had no experience in a working store.” He was a fast learner, because not only did he create his own store – Speedy Mart – but turned it into a franchise. Today there are 45 Speedy Marts and he owns 25 of them. He says, “We have grown because of the employees. Most of those who worked for me for a year or two and have some money, we take them as partners when we find a new store. So we believe in teamwork very much and growing together, because without your people, you cannot grow.” Patel is president of the Asian American Retailers Association (AARA), which is planning to go national. Started last year, AARA has 500 members, who own 1,000 stores, including Krauszer’s, 7-Eleven, Quick Marts, and Pantry One.

“We are fighting for the rights of store owners, because there are so many different taxes and tough laws about selling tobacco,” says Patel. The price of cigarettes in New Jersey is much higher than neighboring states, which makes it difficult for C-store owners to profit on them. He says that the largest profit is in prepared foods, deli and sodas. While the share in lottery sales is just five percent, it is big volume and C-store owners can make almost $1,000 every week in commissions. C-stores are increasingly organizing around tobacco and oil taxes and lottery ticket sales, which are often governed by local and state laws, resulting in a proliferation of organizations. Twelve of these associations have bandied together into the National Alliance of Trade Associations (NATA). “There’s a common thread which combines all of the owners and members of these associations. The fact that all of us belong to the same community – that is the Ismaili Muslim Community,” says Ebrahim Jaffer, chairman of NATA, and president of the Atlanta Retailers Association (ARA). “We are the followers of Aga Khan. The Aga Khan Development Network is the world’s largest human development organization with approximately $300 million and over 60,000 employees across the world.” The organization includes Ismailis from India and Pakistan as well as other parts of the world. NATA represents both major players and small independent store owners. Most of the convenience stores are combined with gasoline sales, which includes brands like Shell, Chevron, Exxon, Diamond Shamrock and Valero. Jaffer, who is from Pakistan, came to the United States in 1973 and after studying in Utah, he moved to California and then to Atlanta to operate convenience stores. He owns several C-stores and gas stations in the metro Atlanta area. “The Ismaili community realized that the convenience store-gas station industry was one that we could get involved with and given our entrepreneurial background, it would be a great entry point in the economic development of the community,” he says.

The Ismailis, who are known to be astute traders, started buying stores, improving them and cutting expenses and increasing sales. Jaffer credits the economic environment of America for this success as it encourages small business ownership, but he also emphasizes the South Asian work ethic: “The fact that you can get in, you can learn the business, you can become the manager, you can lease a store and then go on to own the property and then go on to multiple locations – that is possible because it requires business acumen and hard work and dedication. Given the nature of our historical entrepreneurial background, this was a natural progression and the opportunity was there.” The C-store owners are increasingly developing clout: ARA has established a credit union in Atlanta and the Greater Austin Merchants Association has set up a warehouse in Austin, Texas. NATA is also courted by the big brands: officials held a meeting with Indra Nooyi, CEO of PepsiCo in Houston, while in Atlanta they were invited to the Coca-Cola Company’s headquarters where the NATA flag was flown. Recalls Jaffar Peermohammad, president of GAMA, “My heart was pounding with honor and pride to see the NATA flag being hoisted along with United States, Georgia and Coca-Cola company’s flags.” Ismail Ali is another Ismaili from Hyderabad, India, who owns 10 Shell, Texaco and Citco stores in Austin, Texas, and is vice president of GAMA. He says the strength of the industry is in its ability to withstand economic downturns. He recalls, “When my son graduated from the University of Texas in 2000 the computer industry was booming. The first job was very good, but then in 2003 he was laid off. So he joined me in the business. The convenience store business is recession proof, because everyone needs bread and beer and lottery tickets. I always felt safe in the convenience store industry.” For all the success stories, the convenience stores are also a place of nightmares, of armed robberies and shootings, where sometimes you pay with your life. Just last month 55-year-old Rahul Patel of P.K. Food Store in Tampa, Fl., was fatally shot in his store. He leaves behind a wife and children. Besides armed robberies, there is also vandalism, shoplifting and incidents of people driving off without paying for gas. All the owners said they instruct their workers not to play hero and confront robbers. The trade organizations have been active in conducting seminars with experts and police departments to instruct workers on dealing with safety and security issues, and how to keep the stores well-lit and clutter free, so the interiors are visible from the street.

Often workers have to be taught about the communication gap with the outside world, as became apparent in the recent Operation Meth Merchant, in which several South Asian convenience store owners in Georgia were rounded up for allegedly supplying methamphetamine precursor chemicals to buyers. Human rights groups have charged that racism was behind the targeting of these stores, since 23 of the 24 stores targeted in the undercover operation were Indian-owned. Satya Shaw of AACSA says at the recent convention seminars were conducted to educate owners on avoiding such problems in the future. The other problem for convenience store owners is the labor crunch. As Bipin Patel says: “This being an 18 hour a day cash business, it’s important to have good workers. If a couple of workers don’t turn up then it’s very difficult. That’s why we have stopped buying businesses. The employee crunch is big time, because everyone wants to work for bigger companies where they will get medical benefits. Small businesses just can’t give those benefits.” Nevertheless, many South Asians thrive in the business. Florida is the scene for flourishing South Asian convenience stores with many Circle K, 7-Elevens and independent stores. According to Dinesh Gandhi, after Walmart entered the Florida market aggressively, several convenience store chains were driven out of business and were picked up by Indians, who converted them into independent stores. Michael Shah of Southeast Petro Distributors and All American Oil owns 100 convenience stores cum gas stations in Florida and is also a gas broker. Gasoline is important as it draws people to the convenience store where they end up buying many more products. Shah is an architect who left Gujarat in the 1970s to work in South Africa. He practiced architecture for many years in Connecticut until the family decided to move south to warmer climates and hit upon the gas and convenience store business. Shah has helped many newcomers acquire stores and gas stations. When his son Summit graduated from college he joined his father in the business, and his daughter, who graduated from Georgia Tech, has just started her own gas station-convenience store in Atlanta. Shah says he is planning to get into Atlanta on a big scale. Done right, there is good money in the business, and Shah knows of people who earn $200,000 selling gas and candy in Cocoa Beach in Broward County. They share a community with physicians and professionals and bandied together to buy 36 acres of land to build a Hindu temple and community center. Recalls Shah, “In one meeting with 40 people, which included three doctors and about 35 C-store owners, we raised $5 million in two hours.” Any regrets about leaving architecture? “Not at all, not at all,” says Shah. “Truly speaking, there’s a lot of pride in what I do. I love what I do – and that’s the important thing. When you love what you do and when you do what you love, success is going to be there. That’s the key and that’s what I try and explain when people call me from Detroit or Texas, wanting to start a convenience store-gas business. I tell them come and see it and try it for 3 to 4 weeks before you get into it. It’s very important that you must like it otherwise don’t get into it.”

|

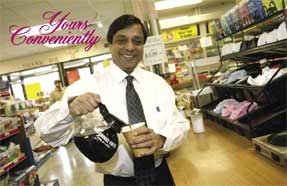

Yours Conveniently