|

For us, immigrants, travel is our raison d’etre. It makes our existence possible. We take it for granted, gripe about its vicissitudes and admire its force to bring us together, to transform our world. Immigrants travel because we want to go home or try to grasp in our infantile charms the idea of home. Immigrants have the sickness of displacement caused by travel. Many of us never traveled anywhere until we migrated here and now we find it is part of our reason to exist. The non resident in Non Resident Indian is about not being home. So we travel to visit home, family, town and country. We also travel for leisure.

That first visit home is memorable. There is such joy to be home again. The air, the smells, the sights and the people, they all look and feel familiar. The home cooked meal hasn’t quite tasted the same in the U.S. The favorite dishes at your favorite eating joints are delightful all over again. This joy of rediscovery cannot be captured in words. A secret unfolding takes place inside you. One of the first things I did on my first visit home was to order bhajias from a local restaurant; no onion ring has ever come close. I recall a friend who longed for a real cup of tea, which he found only at an Iranian restaurant, which have all since vanished. “Double tea with less water” was his formula. The script of such travels back home is familiar to all of us. There are variations to be sure; but sooner or later, you become unsure if you are glad to return, fully anyway. A few days into my visit, I was on a long bus ride, overnight for almost 10 hours. An hour into the journey, the TV monitor on the bus began blaring the sounds of a Hindi movie. No one could conceivably sleep in the middle of that ruckus. Yet, my fellow passengers seemed oblivious, at least on the face of it, and some were even engrossed in the film, which they had likely seen several times before.

Suddenly, the jolt of discomfort hit me. How could one possibly listen to that and how could the driver be so inconsiderate at this hour. What would have been a normal experience before I left was now a discord in my life. Once the anger has subsided though, there was an appreciation for things different, an awareness of how you live in two worlds. Two worlds Yet, almost for therapeutic reasons, we return home – to find our coordinates in two places. We realize that strange and alien as some things might look there, it is still our world. NRIs frequently become impatient with service in restaurants, in hotels, with bureaucracy or even become indignant at times over a little discomfort. Everything about India becomes irritable. All the same, this venting is good, because it reminds us in our “enlightened” perspective that we are growing up as an NRI. Living in a cocoon can be stifling. Even living abroad in the United States, does not help because myopia sets in. The wisdom we immigrants develop as a result of traveling back and forth is unmatched in value. It is beyond any other gifts we have and well beyond any gifts we can give ourselves. Think of the writings of the Nobel Prize winning Non Resident Indian author V. S. Naipaul, who had very little to say about India that was praiseworthy in his Indian trilogy – An Area of Darkness, India: A Wounded Civilization and India: A Million Mutinees Now. After repeated trips, his criticisms have mellowed. He has become a lot more tolerant of a country that proved too complex for his lashing tongue. We travel for the sake of nostalgia – to live in the past that we once did. These trips are also part of our growing up. Travel gives us new eyes, as the French critic Marcel Proust once said. It is the same country, the same people and the same home. Much of it worn and changed over time, but it holds the essences of our memory. We now see things from a different perspective.

When you live in India, you take the slums of Mumbai, the stark poverty or the secret hideouts of your childhood for granted. We hardly even think about them. Separate yourselves over distance and time and your have wider, wiser eyes. Now there is a global worldview with which you see the same slums and poverty. The lyrical charms of your own hideouts are clearer, but with critical detail. We discover new things in familiar places because we travel. Wisdom is never without its bias. As immigrants, we have the power of foreign currency. We know our way around. We can afford things we never did before. Spending is a lot easier now. And yet, we want to be normal, save a little change and pretend to be someone else. It is not uncommon to hear stories of NRIs who want to pass as “natives,” conceal their money and still enjoy the privilege of being better off. We are pardesis in a desi land.

But “native” Indians have developed an uncanny skill in detecting and outing NRIs with pretenses. Once at a historic site that imposes different fees for foreigners and for native Indians, I tried to get away by claiming that I was indeed a resident of India. I tried my Hindi and Marathi on the man behind the ticket counter . But he didn’t want to have anything to do with it. He insisted that I cough up the special entrance fee in dollars that “foreigners” are asked to pay. What did he have to do with demanding more money; he was a government servant after all, I thought. But he unmasked me quickly and rebuked me warning that I was not the first one to run this trick by him. Seems like quite a few NRIs try to “look local.” We also travel for leisure. Have you heard of the running gag that there is always an Indian in any country and in any place you are traveling? Given our robust share of the world population and our growing purchasing power, we are now everywhere. Go to the ski slopes in Austria, an aboriginal village, Disney world, or a remote tourist site in Brazil and you will find a visiting Indian there. We are entering the class of leisure travelers. A whole industry drives this, of course, preying on our desires to be somewhere and curiosity to see the world.

Travel for leisure has a different flavor, a different slant than the travel for necessity, one that takes you home. In both cases, you travel because you can. In the former though, it is because you have to, for emotional, family or psychological reasons. But travel for leisure is made possible by surplus income. It is an expression of power and means. That form of travel, more than any other, is an intrusion. We travel to visit those who cannot travel and enjoy their environment for our pleasure. The travel industry, by definition, is exploitative of the places it promotes, without regard or respect for those who live there. Consider the jewel of India’s travel industry, one of the wonders of the world, the great Taj Mahal. For all the romance and glamour associated with this monument, traveling to the Taj and seeing it are instructive experiences. Clearly, it is the most popular tourism site in India. People go there to be in the presence of one of the greatest monuments in the world. The environment around it has lost any identity of its own. You can witness the foreign currency pouring in from all corners. The city of Agra, with it splendorous past resembles a waiting room, adjoining a great, historic place. It has been drained of its own culture and people. The entire highway leading from Delhi to

Agra, once a prized countryside, showcases how a distinctive region can lose its charms because it is leading to the Taj. Everyone is hawking something. Everyone attempts to speak languages they cannot. As you get closer to the city, the skyline is crowded by an oil refinery. Stories about how pollution is ruining the marble of the Taj are plenty in themselves. The city of Agra is enveloped with smell, thick and polluted air and you have to strain to see local people anywhere. Those who live there are clearly surviving by adjusting to the tourist economy. It does not appear that any of the money that the Taj brings (the fees for foreigners are hefty) or that the hotel industry generates goes to reducing the environmental damage. We are talking not simply of pollution, but also cultural damage. It is as if you are entering a prison and seeing only the prisoner. The surroundings have lost their historic and local cultural character. Is this how tourism promotes itself? Arrogance and indifference allow for such negligence for the distant visual pleasure that the Taj provides. If you take in all the experience, the Taj becomes only a building, a monument without life.

And this is not just the case with the Taj Mahal. The local economies of many places around the world have been displaced by the economies of travel and tourism. But don’t expect inquiring minds to probe these issues in the travel sections of Western newspapers and travel magazines. The New York Times does ask the question: Why we travel? But it proceeds to answer it purely from the perspective of travel as consumption. You are likely to get tips on how India is “made easy” or “how to survive in Delhi for 36 hours,” along with suggestions for places where you can get poolside cocktails. There are reasons (and evidence) to believe that travel actually causes more harm than good upon the places it promotes and the people it needs. Travel may help some people living around the places we visit. But it is marginal at best and it is still patronage. Consider if the money that the Taj brings or what is brought in Rajasthan goes to those who live there. Or imagine Cancun’s surroundings with all that money brought in for the people alone. Think of the economy of Goa! Would they really have all the problems of shortage in funding in public works or education if they were supported by all the money brought in from tourism? We patronize people, not help them. This is why the most popular tourist spots are surrounded by poverty and a shoddy environment if not squalor.

The much ballyhooed NRI class in India, it is said, has spawned a new economy in India, entirely meant to please us, from the shopping malls to regular hangouts. We know well that there is a new India now for us NRIs, mindful of our privileges and resources. How else do we explain the emerging shopping malls, copycat Western hangouts and places of comfort all designed to cater to this moneyed class. It is possible to go to India (or anywhere, for that matter) and live in luxury, sleep in five star hotels, smell the sterile air of air-conditioned rooms, cars and cabs, visit the places you wanted, meet the people you could and return intact from that experience. How different is it from the times of the British, who had servants waiting on them in their plush mansions, with their luxuries of cricket and hill stations and promenades in designated places. They turned their arrogance into patronizing, which is exactly what modern travel allows you to do.

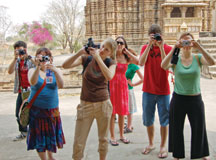

When you are a traveler, take a good look at yourself from the eyes of those who live there. It would be akin to Dutch filmmaker Bert Haanstra’s film, Zoo. In it, we see the whole experience of visiting a zoo from the point of view of the caged animals. Think of how the world appears to them. From the perspective of the locals, we are the picturesque, we are a sight to behold. We appear clownish, with our Bisleri bottles, our hot new sneakers, our hats or sun tan lotions. We have the look of being lost; everything exotic is a purchasable commodity. We could be sold anything. People who live in tourist areas, those who make a living from us, have skills far beyond what we can imagine. Our own pleasures for travel become so important. We arm ourselves with cameras and keep clicking any and every strange sight in our reach. The camera is as intrusive as a gun and given its omnipresence, even more dangerous. All you have to do is invite strangers into your home and let them take pictures of your abode and your family. Imagine this feeling upon those we visit. And yet, we take it for granted that when we travel, we ought to carry a camera. Each person and object that offers a sight out of the ordinary is worth capturing. We celebrate visiting a place by the number of pictures we take. Each image in our album is a robbery. Perhaps the locals should start taking pictures of the tourists so it puts them at unease and makes them aware of a camera’s aggression. With the right disposition, travel can be a humbling experience. You are suddenly aware of different worlds and hopefully it reduces your arrogance and the position of luxury you occupy. The great American writer Mark Twain once warned: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.” Travel can make us humble in our knowledge and about our place in the world.

And India certainly demands humility. Humility in Travel You know the tales of people who packed their bags and assumed a visit to India is a little variation from that to rural Texas or the outskirts of Cancun and gotten the shock of their lives. India can be unforgiving to the uninitiated. It is a country with extreme contrasts and nothing ordinary here works quite the same way there. Those who think the U.S. is diverse country between Los Angeles and New York, with the lovely Mississippi delta shaping the middle character, are gravely mistaken to assume this is diversity. India defines diversity. Language changes with each leg of travel and food with each passing day. Sights and sounds are distinct and there is poetry in that richness. For what we consider order, there is a deeper boredom. Surprise is held in each encounter and if you are ready to see the country, the culture and the people on their own terms, not as showcases for tourism, you will experience life that is varied and complex and forever charming. But all this requires humility, a judgment that does not use the yardsticks of one’s own confinement to read the other.

Nothing quite humbles you as much as India. To the uninitiated, it is a culture shock. Its variety is bewildering and its complexity intimidating. For those with empathy and pity, there is nothing that India offers other than a deepening of stereotypes and prejudices. When you travel to India, even as a returning Indian, there will be many things that appear “strange” or alien. The odd rituals in temples, the wayward strangers walking around without aim, the rickshaw-wallahs who haggle over little amounts of money, the slow speed of bureaucratic paper between two points, the long lines for railway and bus tickets, the slow traffic, everything requires that you come to terms with what you are seeing. A wise traveler defers judgment. He indulges in his experience and lets the world unfold before him. India offers unlimited joy and there are “strange” surprises at every corner.

A recent trip provided a strong lesson in humility to me. I missed a flight in India and had to make my way quickly to Khajuraho to meet up with others in my group. I caught a plane to Gwalior and then drove in the night for almost seven hours. It became one of the most memorable journeys, full of lessons and moments of reflection. First, it would not have been possible without the benefit of my foreign currency to rent a car and drive that quickly so late in the night. The driver was, as always, a man of the world, familiar with all the tricks and tales about people who travel to India. He crisscrosses the North each week, taking travelers from one place to another. Wise and cautious, suspicious of strangers, but fully willing to open his heart to them, he engaged me in conversation throughout the trip. As is commonplace in India, he needed tea (with extra adrak, or ginger) every two hours and enjoyed stopping, just because he felt like it. There was a longer break for almost 40 minutes for tarka dal and rice at a roadside dhaba. Clearly he

was tired as he had been on the road for over 14 hours already, but determined to make the most of his new customer-acquaintance-listener. He warned me a few times to watch for bhoot (ghosts) on the road as he saw a few himself. It was an intense journey. I got into the car as an NRI, mindful that it was an odd hour, and the journey was long. It was also a road little traveled at that hour. With each passing minute, it became clear that the reasons for travel are really about humility and trust of strangers, not about leisure and not about money or souvenirs. After some four hours on the road, he spotted on the side of the road a small hut that seemed like a home. It did not appear to be a dhaba. But he must have known the residents and told me later that the person there stays awake most of the night to offer tea to his driver friends. A younger son, about 9-10 years old, would run to the trucks

or cars with tea and a pot of water. The driver declared it was time for his tea, but I declined any more caffeine at that hour. He took the car aside, reclined his seat and went to sleep. His snooze lasted for 20 minutes, while the car sat in a remote farm. When he woke up, he turned on his lights and right on cue the little kid came by with tea and water. All of us chatted a while about ordinary things. Among the many stories I heard while driving, some of which may have been embellished, were about travelers to India. The driver believed that all travelers who come to India are running from something. It could be something personal or just some artificial idea that India offers solace to lost souls. It was not the first time I heard that belief. What the driver meant was that travelers wear too many masks. They pretend to be what they are not. Some of them pretend they are not NRIs, while some others do. Some pretend to know a lot while few do. Some want to be at home there,

but few try. He was particularly skeptical of those who think they know a lot about India from the Internet, especially those who make online reservations in the belief they are getting the best deals. Some come laden with prejudices and return with deepened impressions. Very few, he said, come to India to be Indians. Just as I was trying to figure out what he was saying, we rolled in front of the touristy hotel in Khajuraho where I was staying. The contrast between the two worlds grew starker than ever. I was entering a world with fewer surprises, with people just like me staying there. The pretenses there were glamorous and comforting. I asked him if he wanted to stay, get some rest and then drive back. He declined with a simple answer: he would sleep better in his car.

The experience told me what travel is about and what it isn’t. How hard it is to travel! I am not talking simply about the difficulties at the airports, delays and lost luggage. But it is hard to defer judgment, to diminish your arrogance and even more difficult to be humble. The people we met in the dark of the night had more to offer in our experiences than the tourists in hotels. The next day, I was at the Khajuraho temples, another great monument on the list of many travel destinations in India. The temples were gorgeous and profound. Their surroundings were dry, but the

grass in the compounds was green. The area had not seen rain in months, but each segment of the lawn in the tourist areas was generously watered. It was easy to identify the NRIs and foreigners from the locals. The moments for the former were filled completely with the selfish consumption of pleasures. This is not about coming home enlightened, I thought. It is not about traveling because I can. It is not about patronizing them with your gestures or foreign currency. Travel is not meant to cleanse you and give you a break from your crises. It is certainly not about seeing the world for the extra thrills you can afford. It is about seeing the world from other perspectives. It is about how ridiculous you look as a traveler to your own land. It is about them worrying about their next day while you wonder about yours. It is about this upside down world that makes them wonder why you come searching for a place they cannot leave.

|

Why We Travel To India