V.S. Naipaul, the Nobel laureate who died at 85 on Saturday, had so many gifts as a writer — suppleness, wit, an unsparing eye for detail — that he could seemingly do whatever he wanted. What he did want, it became apparent, was to rarely please anyone but himself. The world’s readers flocked to his many novels and books of reportage for “his fastidious scorn,” as the critic Clive James wrote, “not for his large heart.” In his obvious greatness, in the hard truths he dealt, Naipaul attracted and repelled.

He was a walking sack of contradictions, in some ways the archetypal writer of the shifting and migratory 20th century. His life was a series of journeys between old world and new. He was a cool and sometimes snappish mediator between continents. Indian by descent, Trinidadian by birth, Naipaul attended Oxford and lived in London, where he came to wear elegant suits and move in elite social circles. “When I talk about being an exile or a refugee I’m not just using a metaphor,” he said. “I’m speaking literally.”

His breakthrough book, after three comic works set in the Caribbean, was A House for Mr. Biswas (1961), a masterpiece composed when Naipaul was 29. It has lost none of its sweep and sly humor. It’s about a character, based on Naipaul’s father, who begins his life as a sign painter in Trinidad and Tobago and improbably rises to become a journalist. The first sign he paints reads, in words the industrious Naipaul seemed to take to heart: “IDLERS KEEP OUT BY ORDER.”

The richest and most eminently re-readable books of Naipaul’s fiction after A House for Mr. Biswas include In a Free State, an intimate suite of stories concerned with colonialism and the vagaries of power. Set in Egypt, America, Africa and England, it won the Booker Prize in 1971. Guerrillas was called “probably the best novel of 1975” by the editors of The New York Times Book Review. It is Naipaul’s most propulsive book. Set in an unnamed Caribbean country where the air is thick with postcolonial British dominion, it offers a complex portrait of the manners and motives of Third World revolutionaries. It is an uncanny meditation on displacement. You never quite know where the novel is heading. Its author would later say, “Plot is for those who already know the world; narrative is for those who want to discover it.” His last great novel, set in postcolonial Central Africa, may have been A Bend in the River (1979).

It is a mistake to compress any gifted writer, perhaps especially Naipaul, down to his politics. His gifts as an observer are simply too large. But political themes came fully into view. His instinctive defense of the locals who led restricted lives under colonialism came into crushing conflict with his bleak view of their societies. Not for him the upbeat, pastel-colored Caribbean novel of uplift. He was pessimistic about the idea of radical political change.

A touchy sense of shame cut through his fiction. “My most difficult thing to overcome was being born in Trinidad,” he said. “That crazy resort place! How on earth can you have serious writing from a crazy resort place?” He may have won the Nobel Prize in 2001 but, from the start, he was a laureate of humiliation.

He began in the 1960s to write about his travels amid the worlds of his fellow colonials. He wrote about India (An Area of Darkness, India: A Wounded Civilization); Argentina, Trinidad and Congo (The Return of Eva Perón); and Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan and Malaysia (Among the Believers). He toured America south of the Mason-Dixon Line for an eye-opening book titled A Turn in the South, in which he commented: “There is no landscape like the landscape of our childhood.”

He was envied for his successes. “Oh for a black face,” Evelyn Waugh wrote in 1963 to his friend Nancy Mitford after Naipaul had won another literary prize. Naipaul was aware of this sort of racism. He once rewrote the racist slogan “Keep Britain White” by adding a comma: “Keep Britain, White.”

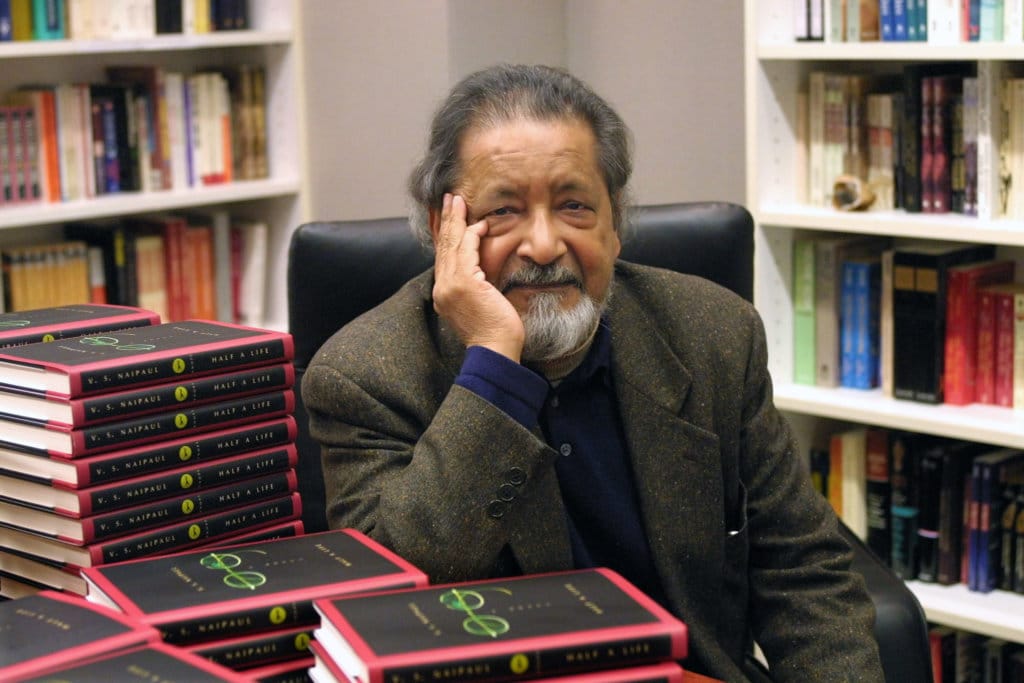

The author V. S. Naipaul at the Westbury Hotel in New York on Jan. 24, 1991. Photo: Neal Boenzi/The New York Times

Naipaul’s unsympathetic views of postcolonial life made him among the most controversial writers of his time. No white Westerner could have spoken as he did. He wrote of the “primitivism” and “barbarism” of African societies. He fixated in India on the lack of plumbing: “They defecate on the hills; they defecate on the riverbanks; they defecate on the streets.” He denigrated the country of his birth: “I was born there, yes. I thought it was a mistake.” He was a critic of Islam.

He was loathed by Third World intellectuals and called, among other things, a “restorer of the comforting myths of the white race” (Chinua Achebe), “a despicable lackey of neocolonialism” (H.B. Singh) and a “cold and sneering prophet” (Eric Roach).

He made enemies as easily as sipping tea. He said: “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me.” He physically abused Margaret Murray, his mistress of many years. He spoke openly about disliking overweight people and about visiting prostitutes. A bindi on a woman’s forehead signifies, he said, “My head is empty.”

He had as many ardent defenders. Ian Buruma, editor of The New York Review of Books, thought it was a mistake to view Naipaul as “a dark man mimicking the prejudices of the white imperialists.” He wrote: “This view is not only superficial, it is wrong. Naipaul’s rage is not the result of being unable to feel the native’s plight; on the contrary, he is angry because he feels it so keenly.”

At its best, Naipaul’s work made these questions nearly moot. He was a self-styled heir to Joseph Conrad, and a legitimate one. “This is what I would ask of the writer,” he once said. “How much of the modern world does his work contain?” Naipaul’s work contained multitudes — subtle and overlapping meanings, only rarely sledgehammer ones. He is the subject of an excellent biography, The World Is What It Is (2008), by Patrick French — a good starting point, along with A House for Mr. Biswas, for those interested in Naipaul’s work.

Naipaul was a difficult man. He cultivated an air of superciliousness. He treated interviewers the way cats treat mice, condescending to them and pouncing on their, in his view, naïve and ridiculous questions. Yet those who knew him also spoke of his personal warmth.

One example will suffice. In her new memoir, A Life of My Own, the English biographer Claire Tomalin writes about becoming ill while at lunch with Naipaul in the early 1980s. He canceled both their orders and requested a pot of tea and a jug of hot milk, which they shared before he suggested a restorative walk by the river. “I decided Vidia was not only one of the great writers of his generation,” she wrote, “he was also the kindest of men.”

Naipaul overcame a great deal, including years of neglect, before making it as a writer. He had determination and a sense of destiny. “I knew the door I wanted,” he wrote. “I knocked.”

© New York Times 2018