The Trump administration’s hard-line immigration policies are predicated, in part, upon the notion that immigrants who are in the country illegally represent a threat to public safety.

The White House, for instance, has sent out regular email blasts to reporters with alarmist accounts of crime committed by undocumented immigrants. President Donald Trump has frequently exaggerated the threat posed by MS-13, a criminal gang originating in Los Angeles whose members tend to be from Central American countries. On Tuesday he wrote on Twitter, without evidence, that Democrats “don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country, like MS-13.”

But the social-science research on immigration and crime is clear: Undocumented immigrants are considerably less likely to commit crime than native-born citizens, with immigrants legally in the United States even less likely to do so. A number of studies published in the past several months clearly illustrate the consensus.

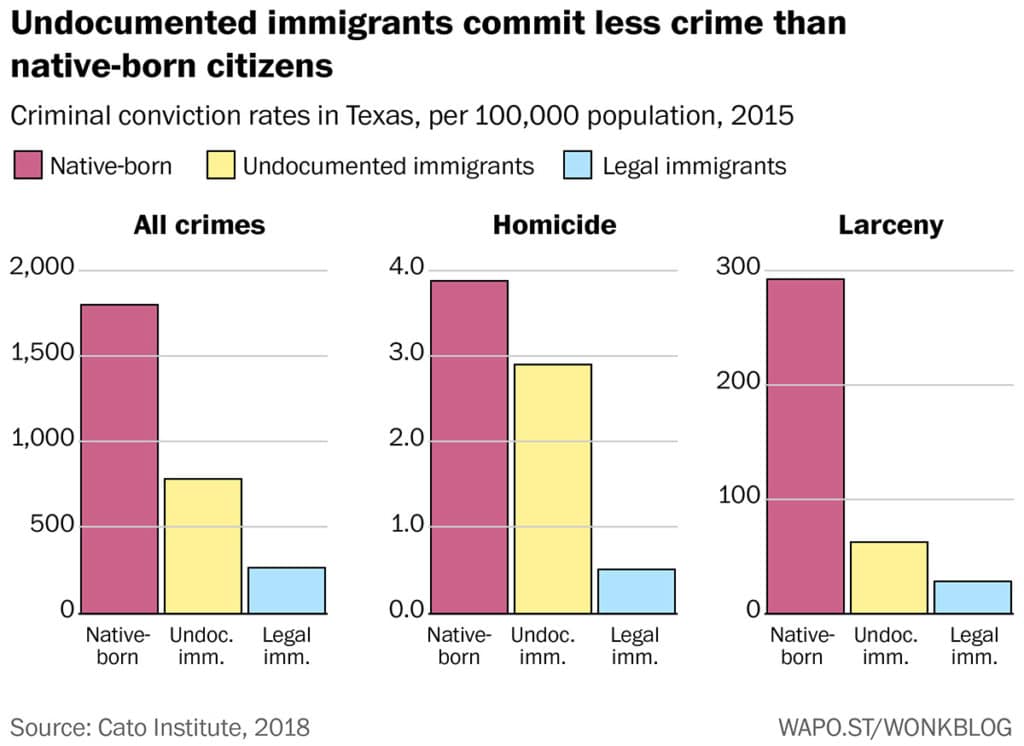

The first study, published by the libertarian Cato Institute in February, examines criminal conviction data for 2015 provided by the Texas Department of Public Safety. It found that native-born residents were much more likely to be convicted of a crime than immigrants in the country legally or illegally.

“As a percentage of their respective populations, there were 56 percent fewer criminal convictions of illegal immigrants than of native-born Americans in Texas in 2015,” author Alex Nowrasteh writes. “The criminal conviction rate for legal immigrants was about 85 percent below the native-born rate.”

The data shows similar patterns for violent crimes such as homicide and property crimes such as larceny. The study did find that immigrants in the United States illegally were more likely than native-born people to be convicted of “gambling, kidnapping, smuggling, and vagrancy.” But as those crimes represented just 0.18 percent of all convictions in Texas that year, they had little effect on overall crime rates.

Another study, published in March in the journal Criminology, looked at population-level crime rates: Do places with higher percentages of undocumented immigrants have higher rates of crime? The answer, as the accompanying chart shows, is a resounding no.

States with larger shares of undocumented immigrants tended to have lower crime rates than states with smaller shares in the years 1990 through 2014. “Increases in the undocumented immigrant population within states are associated with significant decreases in the prevalence of violence,” authors Michael T. Light and Ty Miller found.

That’s just a simple correlation, of course, and it’s well documented that many factors beyond immigration can affect the crime rate. So Light and Miller ran a number of statistical analyses to more clearly isolate the effects of illegal immigration from those other factors. Among other things, they find that the relationship between high levels of illegal immigration and low levels of crime persists even after controlling for various economic and demographic factors such as age, urbanization, labor market conditions and incarceration rates.

All told, Light and Miller sliced the data 57 ways to see whether there was anything they missed, but not one of their analyses showed any positive relationship between illegal immigration and crime. They concluded that not only does illegal immigration not increase crime, but it may actually contribute to the drop in overall crime rates observed in the United States in recent decades.

“Our study calls into question one of the primary justifications for the immigration enforcement build-up,” Light and Miller concluded. ” . . . Any set of immigration policies moving forward should be crafted with the empirical understanding that undocumented immigration does not seem to have increased violent crime.”

These two studies are far from the only ones showing that immigration, legal or otherwise, does not lead to rising crime. But the evidence they present is some of the strongest offered to date. The Trump administration, however, does not seem to be listening.

(c) 2018, The Washington Post