It is hard not to hear about the Apple Watch. News coverage of the early March launch event was widespread, with journalists live-blogging every step of the unveiling. Fans weighed in on the smartwatch through blogs, tweets and YouTube videos. And in case someone, somewhere remained unaware of the device, Apple’s latest iOS update automatically embedded the Apple Watch app on millions of iPhones. The app includes a commercial for the Watch, a 10-minute exposition by head designer Jony Ive and a link to the smartwatch’s upcoming app store. Never mind that the timepiece will not start shipping until late April.

As Apple gets ready to enter a new product category — wearables — another tech giant 10 miles north in Silicon Valley has quietly stopped production of its highest profile wearable: smart glasses. Google has put Google Glass on hiatus pending a redesign. The temporary exit comes after two years of being in the market, first sold to invited testers it called “Explorers” and later the general public, garnering mixed reviews. But Google said it is not giving up on the smart glasses just yet. “We’re continuing to build for the future, and you’ll start to see future versions of Glass when they’re ready,” the Google Glass team said in a January 15 letter posted on Google Plus. “For now, no peeking.”

In a tale of two wearables, dueling tech giants, both known for innovation and deep pockets, have taken contrasting approaches as they enter new product categories. For now, Glass has failed to thrill the public and even ran into privacy issues because of its recording capability. Indeed, Google’s strategy for rolling out its smart glasses is a cautionary tale to others seeking to enter the wearables market. And while Apple might be a marketing whiz, it is getting into smartwatches for the first time and could learn from Glass’s mistakes.

“Already, Apple’s approach is different,” says Peter Fader, a Wharton marketing professor and co-director of the Wharton Customer Analytics Initiative. “Apple is combining two different technologies that we understand: the watch and the smartphone. When they come together, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

That was not the case with Google Glass. “With Google Glass, there’s nothing understood about it. You could say it’s combining a computer or smartphone with glasses,” notes Fader, whose son owns one. “But the things that you do with Google Glass and the way you wear it and experience it is … a great departure from both glasses and the way you use a smartphone.”

Glass initially came without lenses — just the frame. At the top edge, a tiny computer screen sits on one side that can be woken up by tilting one’s head or tapping the frame. Users scroll through screens or execute actions using voice commands or by tapping and swiping a touch pad on the side of the frame. But besides being a novelty, it is not clear why users need a computer attached to the side of their face. “We never quite figured out why it exists,” Fader says. “The sad part about it is, I think it could have been a great success, but Google so totally mismanaged the creation and launch of the product, they just never gave it a chance — and it’s really tough to undo the damage.”

Since Glass was such an unfamiliar product to most consumers, it should have been released in stages, Fader points out. Google should have followed the strategy taken by cell phones when these devices first entered the market in the 1980s: sell the product first to mobile professionals such as real estate agents and doctors for their specific uses, and afterwards to the public. After marketing the product in phases, Google could continue to develop the technology and work on lowering the cost of the $1,500 device. Then, the company could allow buzz about the product to bubble up from users to specialists to well-heeled consumers before reaching the mass market to ensure better adoption, according to Fader. “Google Glass was so radically different they needed a totally different strategy.”

Fader likens Glass to the Segway, an ingenious battery-powered electric vehicle on two wheels that moves when users shift their center of gravity. Unveiled in 2001 on ABC’s Good Morning America, the Segway was marketed to the general public all at once without first convincing them of its usefulness. At an initial price of $5,000, consumers balked even though the technology was revolutionary. Fader notes that the Segway was unfamiliar and the product should have been introduced in stages while the company worked to get costs down. “It should have never gone to Good Morning America with [TV anchors] Charlie Gibson and Diane Sawyer tooling around in it,” he says.

However, there was another problem that was hard for the Segway to overcome: It made the rider look awkward, as though he or she were standing on a rolling podium. Wired magazine once called it a high-tech “scooter” that looked “ridiculous.” The Hartford Courant newspaper in Connecticut said it looked like a “rotary mower.”

One notable exception to the strategy of gradual release was the iPhone, Fader notes. Apple launched the product all at once to the public even though it was a radical departure from the way most mobile phones worked at the time. But consumers bought it after seeing how the iPhone could replace their MP3 music players, video players and cameras and still manage to make phone calls, browse the Internet and send text messages. In addition, its mobile apps expanded the smartphone’s functions, making it a pedometer, flashlight, compass and camcorder, among other tools.

Fader adds that Apple’s marketing brilliance as well as the “halo and built-in trust factor” around the company drove iPhone sales. It also helps that Apple has a cult following. “Apple is the only company in the world that when they announce something, people will line up around the block” to be among the first buyers, he notes. “If [Apple] tells me this is good, I’m going to take a chance.”

‘Just Too Clunky’

Apple smartly positioned Apple Watch not only as a high-tech timepiece, but also as a fashion accessory, according to Wharton management professor David Hsu. That is important for wearables because, unlike smartphones that are tucked into pants’ pockets or bags, wearables are worn as part of the user’s ensemble. Google banked on the Glass’s revolutionary technology to drive interest, without taking into account that most people will not wear something that will make them look silly. Last year, Google tried to rectify Glass’s image by reaching a deal with luxury eyewear maker Luxottica to put it on Ray-Bans and Oakleys. Even so, Luxottica founder Leonardo Del Vecchio told The Financial Times last fall that it would “embarrass me going around with that on my face.”

An early adopter of technology, Hsu says he tried on Glass but did not like it. “It’s just too clunky. There’s this social element that just really wasn’t acceptable. You can flick through pictures or screens by essentially putting your finger up to the glass and flicking it from the outside. It just looks ridiculous.” Google Glass has been the object of social satire as well, even earning a sketch on Saturday Night Live that made fun of the concept of wearing a computer on one’s head.

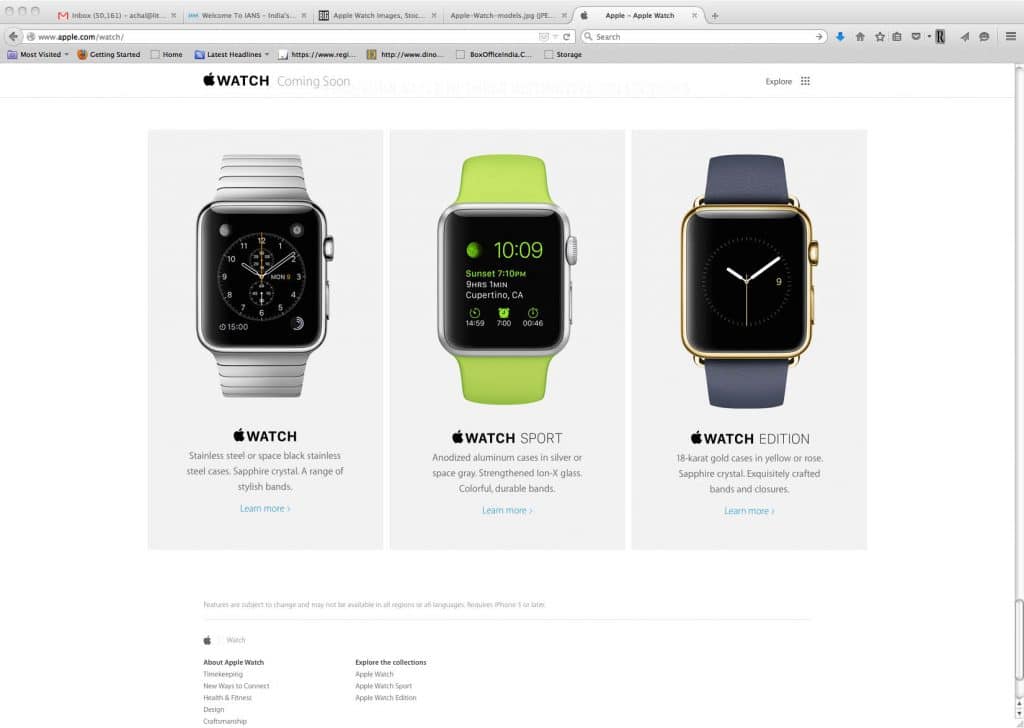

In contrast, Apple designed Watch to look as similar to a traditional timepiece as possible, down to the round crown on the side. The crown is “comforting,” Hsu says. “A lot of times when companies introduce something new, they want to include a familiar component.” Indeed, Apple CEO Tim Cook took time to push the smartwatch’s design, as well as the technology behind it, at the device’s launch event. Priced from $349 to $17,000, Apple Watch comes with a choice of colorful rubber, leather or steel bands, some wrapping magnetically around the wrist. It even comes in 18 karat gold. People can switch watch faces as often as they want, just like they swap out smartphone wallpapers, with a choice of many designs including Mickey Mouse, space scenes and a classic watch.

That is not to say that every wearable must be fashionable. Hsu remembers a time when many people hooked Bluetooth headsets to their ears to receive and make phone calls without having to whip out their mobile phones. “People were just walking around seemingly talking to themselves,” he notes. The headset looked awkward, but it was useful and people got used to seeing it in public. However, “Glass is never overcoming that,” Hsu adds. “It just did not enter the mainstream, and it wasn’t even clear it was intended to do so.”

According to Hsu, Apple’s positioning of Apple Watch as a fashion accessory has a second benefit: It gives consumers another reason to buy it. If Apple Watch was marketed mainly for its technical merits, then people might question why they would need another digital device that performs many functions already accomplished by their smartphones. But a fashion statement is something else. “Maybe as you’re getting dressed, you won’t feel complete without your accessory,” he says. “There’s more of a fashion perspective and customization, which is really quite a break from their computing products.”

Time for Competition

Competitors have certainly paid attention to Apple Watch’s fashionable side. Days after Apple Watch’s unveiling, luxury Swiss watchmaker Tag Heuer announced that it was developing a smartwatch in partnership with Intel and Google’s Android Wear, a version of the Android operating system designed for wearables. David Singleton, director of engineering for Android Wear, said the partnership will create “a better, beautiful, smarter watch.” It is notable that Google’s former subsidiary, Motorola Mobility, developed a smartwatch called Moto 360 that a tech reviewer once likened to a “hockey puck” on a wrist.

Google has been getting wiser about design. In January, it put the Glass division under the management of former Apple executive Tony Fadell, who joined the company after Google bought smart gadget maker Nest, according to news reports. Before he founded Nest, Fadell led the Apple team that created the first 18 versions of the iPod and the first three generations of the iPhone. Fadell will have his hands full reinventing Glass.

Another problem with Glass was that its models did not materially improve after each version, Hsu points out. For example, between versions 1 and 2, the most notable changes were a doubling of the memory to 2 GB RAM and the addition of prescription frames. In contrast, “the classic Apple move is that with each version, they hold the price steady but offer a lot more functionality or technical specifications on the hardware,” Hsu notes. He expects Apple Watch to follow the same strategy, which has worked well for the iPhone. “I don’t see why that also wouldn’t hold true in this category, as well as the yearly commitment to try to upgrade the device.”

Google Glass also launched without offering an array of apps that would have convinced people to buy it for its many uses, especially since it was expensive. “They never really got all the apps going,” Fader notes. In addition, many websites were not compatible with the Glass screen and did not work properly. “Certain things weren’t well configured for it, and certain things don’t work on it.… They just never built it out,” Fader says. “Functionality was very limited because they rushed it to market quickly.” At the recent SXSW festival in Austin, Texas, Google X chief Astro Teller, under whom Google Glass was created, admitted that the company made a mistake by releasing it before it was a finished product, according to a story in Vanity Fair. As a result, users were disappointed.

In contrast, Apple took its time creating its watch and did not mind being late to the market. But when the smartwatch launched, it arrived with many apps familiar to users and synced with their iPhones. Not only could it answer calls, show messages and notifications, track physical activity as well as tell time, the Watch could also open hotel rooms, check travelers in at the airport, prompt one to exercise, act as a remote control, and even send scribbled drawings to other users. “The ecosystem is pretty much in place,” Fader notes.

Of course, Watch has its own limitations. One of the biggest drawbacks is its battery life. The watch’s many functions drain the charge after 18 hours and so users must be dedicated enough to charge it daily, Hsu says. That compares to about once every five days for his Pebble smartwatch, based on his usage.

Another disadvantage is the cost. While Apple Watch comes in a range of prices, even at the low end at $349 it is generally more expensive than many rival models. Some Jawbone smartwatch models can cost under $100, while Moto 360 starts at $250. The Sony SmartWatch 3, the Asus Zen Watch and Samsung Gear Live hover around $200. However, Apple Watch does come with many more functions than its competitors.

Hsu notes that he hoped Apple Watch would offer more health features. The Pebble’s activity tracker motivates him to change his behavior — if it shows him as too sedentary, he becomes more active. He was looking for Apple Watch to offer more sophisticated functions so he can track his health even more closely. While he still plans on buying Apple Watch, “I was among the ones disappointed there weren’t more health applications being rolled out at launch,” he says.

The Killer App?

As attractive as Apple Watch may be, it still faces the challenge of getting people to adopt it, a dilemma faced by many wearables. At present, only 1% to 2% of U.S. adults have wearables compared to 65% who have smartphones, says Mitesh Patel, a Wharton professor of health care management and a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

According to Patel, health care could be the application that would lead to greater adoption. “Everybody cares about their health, and if these devices have some role to play in that, then that can help spur their adoption,” he says. “However, there are a significant number of challenges, including affordability, accessing these devices and then remembering to wear them all the time. And there are still a lot of questions to be answered in terms of their impact. But I do think there’s significant potential, and health care is an opportunity that these wearables may be able to take advantage of.”

However, there is another challenge. More than half of the people with wearables eventually stop using them within six months, Patel adds. “Potentially, if it’s a watch that does more than sit on your wrist, people will wear it, but we will have to see.” For long-term adoption, wearables worn for health reasons have to successfully cause people to change their behavior. “I think wearable devices have demonstrated their role in fitness and wellness,” he notes. “The question is, does it actually improve people’s health over the long term? We don’t know, but at least there is some role for monitoring people’s health, and I think that’s the strength of wearable devices.”

A major opportunity for wearables is their role in helping people manage chronic illnesses, according to Jeff Voigt, principal at Medical Device Consultants of Ridgewood, New Jersey who recently moderated a health wearables panel on Wharton Business Radio on Sirius XM. For example, wearables can monitor a diabetes patient daily and send the data to the doctor for analysis. “That’s where I think the big play is,” he says. However, wearables have to be easy to use and protect patient privacy, which Voigt believes eventually will be worked out.

For now, Wall Street is bullish on Apple Watch. Market estimates for 2015 shipments of the smartwatch range from 10 million to 40 million, according to a March 10 story in The Wall Street Journal. That would easily eclipse the 720,000 smartwatches running Android Wear that were shipped globally last year, out of a total of 4.6 million smart bands, according to analysis firm Canalys. Apple could blow open the market. The firm said Apple Watch is expected to “dramatically grow the market for smart bands and wearables overall.”

Fader believes it will be hard for Apple Watch to fail. “It can’t be a disaster,” he says. “Its success might be modest, but nobody is going to look at the Apple Watch and ask, ‘What were they thinking?’ Whereas with Google Glass, nobody can say, ‘Boy, that was a good idea.’