It started cordially, with an exchange of fence-mending letters between estranged neighbors. It ended abruptly, with a special-edition postage stamp whose honoree was viewed as a hero by one side and a terrorist by the other.

The collapse of the recent, short-lived thaw between Pakistan’s new government and the country’s longtime nuclear-armed rival, India, was much more than a postal change of heart. It was rooted in decades of bad blood and bouts of armed conflict, lately exacerbated by a war of words and resurgence of violence in the Kashmir region, which is claimed by both countries. There was also the matter of the killing and reported mutilation of an Indian border guard.

The hostile, 70-year history of Indian-Pakistani relations is littered with hopeful gestures – invitations, meetings, border ceremonies and proposals for confidence-building measures – that have been doomed by mistrust, insults, violence, conspiracy theories, charges of warmongering and deliberate sabotage by hawks in both camps.

But Pakistan’s new prime minister, Imran Khan, entered office last month eager for a fresh start, immediately declaring that if India took one step forward, “Pakistan will take two.” He invited an old friend from India, retired cricket player Navjot Singh Sidhu, to his inauguration, where a news photo of the turbaned Sidhu hugging Pakistan’s uniformed army commander was an instant national sensation.

In India, Sidhu’s high-profile appearance at the event drew accusations of treason from hawkish commentators, but Khan appeared to take heart when he received a congratulatory letter from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a Hindu nationalist whose tenure has seen a rise in domestic anti-Muslim attacks and threats of military action against Pakistan.

On Sept. 14, Khan formally invited Delhi’s foreign minister to meet his Pakistani counterpart on the sidelines of the current U.N. General Assembly session in New York, calling for “constructive engagement” between the two governments. On Sept. 20, India initially accepted, with a meeting penciled for this week. But the next day, it abruptly canceled the meeting, humiliating Khan and setting off a new round of rhetorical recrimination and muscle-flexing.

India’s statement cited two causes for the cancellation. One was the recent killing and reported decapitation of an Indian guard by what it called “Pakistan-based entities” on the border between the two countries. The second was Pakistan’s issuing of 20 commemorative stamps that India charged were “glorifying a terrorist and terrorism.”

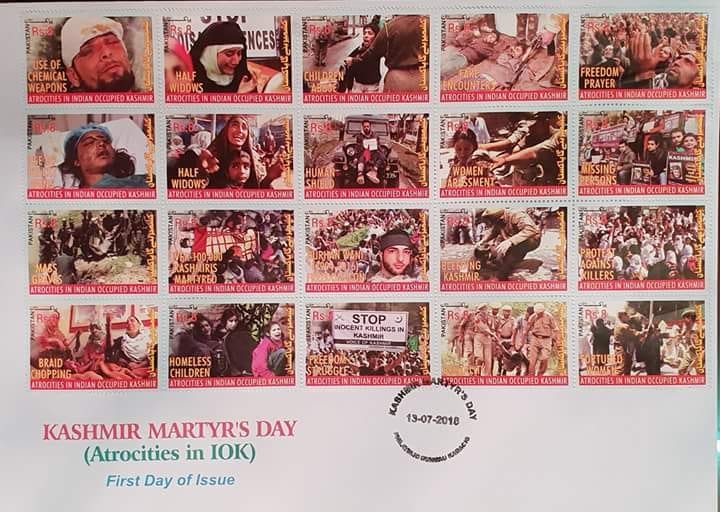

The stamps depicted Burhan Wani, a 22-year-old Kashmiri separatist rebel commander and folk hero to many young Kashmiri Muslims. He was killed in a shootout with Indian troops in July 2016, triggering months of violent public protests in the Indian-controlled portion. The stamps proclaimed Wani a “freedom fighter” and decried “atrocities” in Indian Kashmir, with blurry backdrops of violent and abusive scenes.

Although the stamps had actually been issued before Khan was elected in July and became prime minister in August, India’s statement attacked him harshly, saying that behind the proposal for talks to “make a fresh beginning, the evil agenda of Pakistan stands exposed, and the true face of the new Prime Minister of Pakistan has been revealed to the world.”

India’s army chief, Gen. Bipin Rawat, went further, telling Indian press outlets that the country needs to take “stern action to avenge the barbarism” being carried out by both Pakistani terrorists and army troops. “It’s time to give it back to them in the same coin,” Rawat said. “The other side must also feel the same pain.”

The rebuff stunned Pakistani officials, especially Khan, who tweeted Sunday that he was “disappointed at the arrogant & negative response” to his outreach for peace discussions. Military leaders also bridled; the army spokesman. Maj. Gen. Asif Ghafoor, declared that the government seeks dialogue rather than war with India, but that “Pakistan is a nuclear-armed country and is ready to respond to Indian misadventures.”

The Foreign Ministry rejected Indian allegations of any Pakistani involvement in killing and mutilating the Indian border guard, and it defended releasing the stamps honoring Wani. By “falsely raising the canard of terrorism,” the ministry said, “India can neither hide its unspeakable crimes against the Kashmiri people not can it delegitimize their indigenous struggle for their inalienable right to self-determination.”

As the tenor of bilateral diplomacy returned to belligerent finger-pointing, some Pakistani commentators leaped on Khan as a naive, overeager neophyte in dealing with a sophisticated adversary. Among the most critical was Talat Hussain, a columnist and TV news analyst, who mocked Khan for plunging hastily into a treacherous diplomatic waters, sending “sweets and flowers” to the enemy and invoking “Wilsonian idealism” in his appeal for Indian rapprochement.

“This is a shattering setback,” Hussain wrote in The News International newspaper Monday, arguing that any potential fresh start between the two governments had now been lost in a new round of recrimination. India, he wrote, has taken Khan’s “overzealous desire for a handshake as a sign of Pakistan’s weakness and has sprayed vitriol on its face.”

Other observers here took a longer view, saying that Pakistan and its new leaders need to focus on achievable goals with India and avoid raising the bilateral temperature out of pique. Some noted that Modi is facing elections next year and needs to reinforce his nationalist credentials at home, but that it remains in both countries’ interest to prevent serious conflict, especially nuclear war.

“Let India refuse to talk and let Pakistan continue to respond with talk of peace,” Imtiaz Alam, president of the South Asian Free Media Association, wrote this week. “Whatever the domestic pressures on the leaders of both countries, “the paradigm of mutually assured destruction and the mind-set of enmity will have to be shed . . . if we want to live in peace and as good neighbors.”