|

For most Americans, experimentation with Eastern spirituality or culture starts and ends with “Chai tea latte” or Henna tattoos. But for some it involves far deeper immersion, occasionally even more serious than most Indian Americans would care to acknowledge.

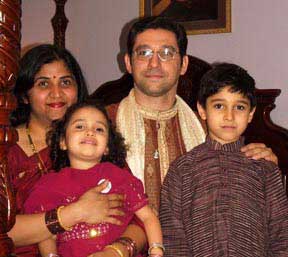

Brian Greenwald says the turning point in his life came when he stopped looking for the answers in drugs and alcohol and to find them instead in simple, dharmic (righteous) behavior and meditation. Brian Greenwald, 36, of Lansdale, Penn., is an active member of Sahaja Yoga, a meditation group founded by Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi Shrivastav in 1970. A self-confessed spiritual seeker, you may find Greenwald on any given evening relaxing in his home in suburban Philadelphia in a kurta pajama, listening to Hindustani ragas and playing with his two children Ganesh, 8, and Sangeeta, 3. Greenwald, who has been married to Puneiite Gouri Shete for the past 12 years, is a technocrat by profession and swears by how Sahaja Yoga uplifted him from the murky world of drugs and alcohol and turned him into a sober, serene and secure individual. This computer systems graphics designer says he was seeking spirituality in relationships, money and literature so intensely that he couldn’t articulate it any other way except by singing about it in his band, “The Skinks,” in the bars of Philadelphia in the early 1990s. Then he happened to go to a Sahaja Yoga meeting and actually felt the experience of meditation. He said in that moment all his thoughts melted away, he felt very light, in control of himself and this feeling of pure joy stayed with him all day long. Within days, Greenwald was hooked to this yoga, where all he had to do was sit calmly and meditate on his kundalini energy, residing at the base of the spine. A few weeks later, a friend took him to a rock concert where they consumed LSD. As soon as the drug hit him, he started hallucinating. Out of curiosity, he tried to meditate on his Kundalini energy and immediately the hallucinations vanished. He felt in control and sober even though LSD typically takes anywhere from 8 to 10 hours to wear off. After many years of partying, summers spent in the French Riviera, winters skiing in the Austrian Alps, countless galas and high profile friends later, Gregoire de Kalbermatten, a career United Nations diplomat, says he was tired and began searching for a “high” deeper than the best alcohol, or the fastest car.

Greenwald says that was the turning point in his life: to stop looking for the answers in drugs and alcohol and to find them instead in simple, dharmic (righteous) behavior and meditation. He is planning to send his children to a Sahaja school in Dharamsala, in Himachal Pradesh, India, as “you can’t get the Indian grounding in spirituality anywhere else in the world.” This is quite a turn around from the 1970s and the 1980s, when affluent Indians were known to bring their full term pregnant wives to Europe or America, so they could give birth there in hopes of gaining citizenship and western schooling for their children. Gregoire de Kalbermatten, a career United Nations diplomat for the past 20 years, currently on assignment in Germany, also sent his two children Macchendranath and Niranjana for their entire education to the Sahaja school in Dharamsala, India. Niranjana is graduating with an average of 5.5 on a 6 point scale from the Institute of Advanced International Studies, Geneva, the alma mater of UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Kalbermatten was born in royalty, to a Swiss baron’s family in 1949 in Lausanne. He lived the high life, managing his family’s various businesses and globe trotting, looking for the next great high. After many years of partying, summers spent in the French Riviera, winters skiing in the Austrian Alps, countless galas and high profile friends later, he says he was tired and began searching for a “high” deeper than the best alcohol, or the fastest car. He was a sick, tired, cynical man in his twenties when he went to meet Shri Mataji in London, who, he says, took him under her wing, cured him of his various maladies and helped heal him emotionally and physically using his Kundalini energy. Now, 30 years later, Kalbermatten is a father figure in Sahaja Yoga, down to earth, exuding gravitas, quite in contrast to the helpless hippie he was in the 70s. A recent painful divorce forced 41-year-old Kimberley Coulombe, of Mill Creek, Wash., to take an honest look at her lifestyle. Raised a Southern Baptist in Nashville, Tenn., she says the Hindu philosophy of Karma, forgiveness and sincere surrender to the divine liberated her from the rage she felt against her husband for walking out on her and their two kids two years ago. Robert Rose was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s admonition to admonition to “Be the change that you want to see in this world.” In one night, Coulombe went from an active, secure woman, to a single mom trying to raise her two children Christopher, 17, and Nathan 13. She says she turned to self destructive behavior patterns and was diagnosed with kidney disease. During this darkest hour of her life, she decided to explore the “Atma-Paramatma” equation in Buddhism. She says she realized she was only the spirit and not this mind or the body, which helped her on her road to recovery. She stopped her panicked search for a romantic anchor in her life and now has bemused empathy for friends obsessing over their life partners. Christopher has been so impressed by his mother’s transformation that he is contemplating studying Eastern meditation in India. Seattle-based Sher Mard Hakeemi, originally Paul Turncott, 42, gravitated to Eastern spirituality through poetry. He has been a follower of the Chishti order from India for the past three years. Hazrat Inayat Khan brought this tradition to the west in the early 1900s. Hakeemi, a maintenance man working the graveyard shift, was so influenced by Rumi’s lyrical sonnets that even his prose reads like poetry. He was a Pentecostal preacher in the early 1980s and dabbled in Wicca, a form of neopaganism. But now, he says, he has found his calling in Sufism. He says growing up in Syracuse, NY, he also was trying to find the meaning of life in relationships and literature, but didn’t really arrive at a satisfactory answer. Since coming to Sufism, he says, he has learned to see how his ego and superego governed his life. Currently Hakeemi is trying to reverse that, while weaving Sufism with anthropology at Edmonds Community College. Mahatma Gandhi was the inspiration for Robert Rose, the 47-year-old owner of Brant Photographers in Bellevue, Wash., who is involved with charitable work for disabled children in Nepal and India for the last 9 years. Rose, along with the Rotary Club, has adopted a project in Kathmandu, Nepal, to build houses, schools, and provide computer access, clothing and bedding to the disabled. He says he was 16 years old when he first went to Kolkata as an exchange student. He stayed there for eight months with an Indian family, which now lives in Seattle and who he describes as his “Indian mom and dad.” He was introduced to Gandhian literature and says he was blown away by Gandhi’s lifestory. Now Rose says he is inspired by Gandhi’s admonition to “Be the change that you want to see in this world.”

For most Americans, experimentation with Eastern spirituality or culture starts and ends with “Chai tea latte” or Henna tattoos. But for some it involves far deeper immersion, occasionally even more serious than most Indian Americans would care to acknowledge. |

Searching East