For anyone who grew up in India during the second half of the 20th century, ice cream is inseparable from the name Kwality.

When the brand arrived in the country in the 1950s, it awakened a nationwide infatuation. During sweltering Indian summers, people would dash to the lit-up cases of Kwality at their local dime store for a block of nutty butterscotch ice cream, or the triple-layered ice cream bar called cassata. But its popularity waned after a corporate takeover left its taste altered.

Now, a take on the Kwality brand in the United States (also under the name Kwality) is inspiring a kind of childlike elation: lines out the door, breathless Yelp reviews and daily demands for more stores to open.

The cookbook author Raghavan Iyer recalls his first experience tasting Kwality’s vanilla ice cream as an 8-year-old in Bombay. “It was fresh, white, rich and creamy, with no icicles,” he said. “It was something totally elusive.”

The fluffy tufts of cream were silkier and more melt-resistant than kulfi, with flavors that were wide-ranging and whimsical.

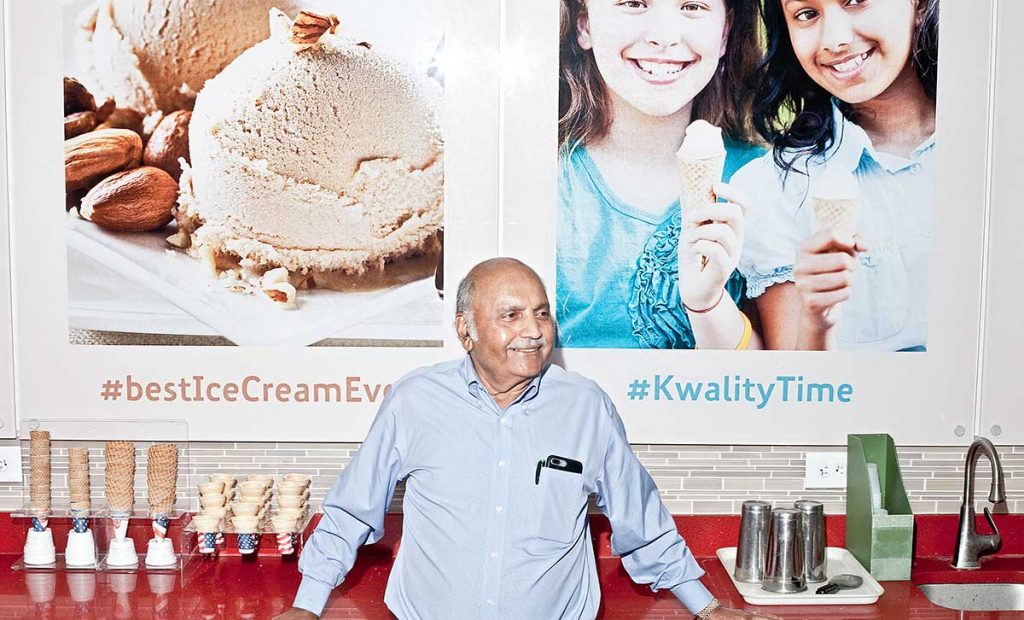

The brand became ubiquitous, and was acquired by Unilever in 1995 — leaving the company’s chief food technologist, Kanti Parekh, without a job. Parekh, a cheerful scientist with a hearty laugh and a deep love of sweets, developed some of the company’s most beloved flavors, like butterscotch and mango. But after the acquisition, Parekh said, “they started modifying certain flavors and lowering the milk content to reduce costs.”

“What ice cream I developed was totally lost,” he added.

That year, Parekh left India for New Jersey to consult on quality control and ingredient selection for packaged foods, but ice cream remained his favorite hobby. “Any town I would visit, I’d count up how many ice cream shops there were, and then taste all of them,” he said.

One day in 2001, a friend approached him about developing desserts for his Indian restaurant. Parekh happily agreed, and, using the same methods he had developed for Kwality, made a few batches of ice cream.

Soon, restaurant patrons were begging Parekh to start his own ice cream shop. Just two years later, equipped with his recipes and a name he knew would connect with his Indian customers, he opened Kwality Ice Cream in a small strip mall in the Little India section of Edison.

“We used the same name to capitalize on the good will the brand had built,” he said. “We wanted people to think of the back-home taste.” The word Kwality, he added, was not trademarked in the United States, so he felt free to use it. (Unilever, which still produces the original brand under the name Kwality Wall’s, did not respond to requests for comment.)

The design of the tucked-away shop plays off the nostalgia of American ice cream parlors — bright pops of red on the walls, posters of caramel drizzling temptingly over a sundae, a flashing neon sign — though the ice cream’s taste appeals to a nostalgia of a different sort.

That distinctive flavor profile was specifically engineered by Parekh to appeal to Indian palates, which he observed are dulled by the vast consumption of spices.

“They recognize flavors only if they are intense,” he said. “If you look at ice cream made with more sugar and less butterfat,” as with U.S. brands like Dairy Queen or Ben & Jerry’s, “you are tasting the sugar first, then you taste the water, and the cream taste is only slightly at the end.”

As a result, Parekh’s formula centers on milk with high butterfat and very little sugar. Over time, he has made a few upgrades to his original recipe, increasing the butterfat content to 14 percent (as opposed to the original Kwality’s 10.5 percent), and adding liquid flavorings he developed with a scientist at Rutgers University.

The end product is an ice cream that is luscious, like a frozen whipped mousse, and aromatic — pure, powerful and elemental in its taste, like biting into the platonic ideal of a mango, or melting a piece of toffee on your tongue. It’s a sensation that his Indian customers immediately recognize. “It is what my childhood memories are made of,” the chef and TV personality Maneet Chauhan said.

These days, Parekh’s company has 10 locations across the country, in cities with heavily concentrated Indian populations, like Fremont, California, and Irving, Texas. There’s also a factory adjacent to the flagship, where the ice cream is made fresh daily and shipped out in temperature-controlled trucks.

Parekh has slowly added new flavors like meetha paan, based on the sugary, fennel-seed-stuffed betel leaf snack, and frozen treats like ice cream falooda, a rose-flavored sundae layered with vermicelli noodles. The crowds show no signs of subsiding.

In Parekh’s eyes, there is no better business proposition than running an ice cream shop.

“Everybody likes ice cream, the sky is the limit with flavors, and it’s a smiling business — after people eat ice cream, they are always happy.”

“My life’s mantra,” he continued: “One God, one wife, one ice cream.”

© 2017 New York Times News Service