Entertainment

Racing Series Helps Show the Way to a Battery-Powered Future

A Formula E race in Zurich, June 10, 2018.

Photo Credit: Elisabeth Real/The New York Times

Back in the early days of the automobile, racetracks were proving grounds for newfangled inventions like shock absorbers, disc brakes and seat belts.

Something similar is happening at the dawn of what may be the age of battery-powered transportation. It was on vivid display in Zurich last month, as the silence of a warm summer Sunday was broken by a high-pitched sound reminiscent of the rebel fighters attacking the Death Star.

The whine came from battery-powered race cars running laps on a course laid out on the streets of Zurich — the first urban circuit race in Switzerland in more than half a century. On June 10, the normally staid Swiss banking city hosted the Formula E series, which will culminate in New York City on July 14 and 15.

Formula E, the electrified cousin of Formula One, is first and foremost about marketing, a 140-mile-an-hour riposte to those who think battery-powered cars are part of a conspiracy by tree-huggers to take the fun out of driving.

But the racing series, which has attracted support from major automakers like Renault, Volkswagen’s Audi division, Mahindra of India and Citroën, is also the place to test out new ways of addressing the unique challenges of battery-powered transportation: range, charging technology and management of the performance-sapping heat that bedevils electric cars.

A pit crew member for Renault’s team during preparations for a Formula E race in Zurich, June 10, 2018. Photo Credit: Elisabeth Real/The New York Times

Formula One, for all its immense popularity, no longer produces many innovations that are useful in mass-market vehicles, said Sébastien Buemi, a driver for the Formula E team sponsored by Renault.

“The good thing with Formula E is that you can develop many things that you will be able to transfer to road cars,” said Buemi, who has also driven in Formula One.

For example, he said, the powertrain in the Renault Zoe, a compact vehicle with a maximum range of about 150 miles per charge, is based on a Formula E design. “A Formula One engine is impossible to put in a road car,” he said.

During a pre-race stroll though the pit area in Zurich, it was obvious that managing the heat generated by high-voltage electric car batteries is arguably a more vexing problem than range or charging time.

ABB, the electrical equipment company based in Zurich that is Formula E’s lead sponsor, has demonstrated technology that needs just 8 minutes to zap enough power into a battery for about 120 miles of driving. But a recharging station with six of these high-voltage chargers would put enough strain on the electricity grid to cause a blackout and melt ordinary power cables, said Ulrich Spiesshofer, ABB’s chief executive.

ABB, which is supplying recharging equipment for Formula E and has ambitions to be the global leader in charging stations for electric cars, sees the series partly as a way to generate public support for infrastructure investments.

“When you have a race car that accelerates and brakes all the time in a very extreme way, in humid conditions, in cold conditions, in wet conditions, in dry conditions, it’s a great opportunity” to test new technology, Spiesshofer said.

The heat was a particular problem here, where the race-day weather was sunny and hot enough to attract crowds of bathers to the shores of Lake Zurich, a stone’s throw from the course.

The problem, it must be said, is not quite solved in a way that would make sense for everyday driving. Shortly before the race began in the late afternoon, pit crews shoveled nuggets of dry ice directly into the air intakes of the race cars to keep batteries cool. Some teams employed a decidedly low-tech cooling method: shielding their battery and motor compartments with ordinary umbrellas.

Formula E teams and their auto industry sponsors can gain a competitive advantage if they can work out a better solution than rivals to such problems. And those advantages could translate from the track to the sales floor.

BMW, which will compete as a manufacturer next season, assigned the same engineering team that works on the company’s i Series battery-powered vehicles to design technology for Formula E.

“The experience they have will have an influence on what they do next in production,” said Jens Marquardt, BMW’s director of motor sport.

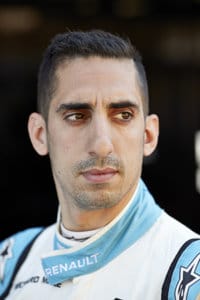

Sebastien Buemi, a driver for Renault’s Formula E team, at a race in Zurich, June 10, 2018. Photo Credit: Elisabeth Real/The New York Times

The BMW team developed a motor for next season that is half the weight and a third the size of previous generations, while delivering twice the performance, Marquardt said.

The motor would be too expensive for mass-market cars, he said, but some of the know-how that went into it — which Marquardt declined to describe, for competitive reasons — is transferable, he said.

“What is happening in Formula E is exactly like the early days of motor sport,” he said.

One area where teams compete intensely is in systems that recapture energy from braking and feed it back to the battery. All the Formula E teams use the same battery and deploy two cars during the race, switching to the second when the first runs low on juice.

The car switch boldly underscores the biggest complaints about electric vehicles: limited range and slow charging. But the technology is improving quickly. Next season, the Formula E cars will get new, more efficient batteries that will last the entirety of the roughly 60-mile races, which take about an hour to complete.

Still, making the most of the finite store of electrons will remain crucial to Formula E tactics. The more cleverly that teams can contrive combinations of software and mechanics to recover energy when the cars slow for curves, the more power they can unleash on straightaways.

“The race is all about energy saving,” Paul Fickers, engineering director for the team sponsored by NIO, a Chinese electric car startup, said on the sideline of the pit area. “You learn a lot about magnetic fields.”

The driver who best mastered the Zurich course was Lucas di Grassi of the Audi Sport ABT Schaeffler team. But the New York City event, a doubleheader that will determine the season championship, will be a contest between Sam Bird of DS Virgin Racing, who was second in Zurich, and Jean-Éric Vergne of the Chinese Techeetah team, the driver with the most points this season. Bird is the only driver with a chance of picking up enough points on the Brooklyn track to surpass Vergne.

The Zurich event was the first legal car race on Swiss streets since 1954. Switzerland banned urban racing after a horrific accident in 1955 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans race in France. A Mercedes-Benz ricocheted off the track and into a spectator area, killing more than 80 people, the worst disaster in racing history.

But Formula E’s green credentials helped persuade Swiss officials to lift the racing ban. Though Formula E cars aren’t exactly quiet, they produce much less noise than the gasoline-powered Formula One cars, and the electric cars are emissions free — although some Zurich residents pointed out that the vehicles involved in building the race venue generated plenty of noise and pollution.

As European cities increasingly restrict traffic in an attempt to cut alarming levels of air pollution, Formula E demonstrates what may be the auto industry’s best hope for remaining welcome in urban areas.

“A lot of cities told us there is no way we would do a race with internal combustion cars,” said Benoit Dupont, head of sporting for Formula E. “What we can do,” he said, “we can do because we are electric.”

© 2018 New York Times News Service