| This is my prayer to thee, my lord —

Strike, strike at the root penury in my heart. Give me the strength to lightly bear my joys and sorrows. Give me the strength to make my love fruitful in service. Give me the strength never to disown the poor or bend on my knees before insolent might. Give me the strength to raise my mind high above daily trifles. And give me the strength to surrender my strength to thy will with love. — Rabindranath Tagore

To an uninitiated reader, the above prayer could easily be attributed to a Christian mystic, such as Ignatius of Loyola or Francis of Assisi or Teresa of Avila. Instead, the prayer came from the heart of a Hindu, India’s great poet-mystic Rabindranath Tagore. That this prayer feels familiar and is appealing to Christians should not be surprising, because Tagore valued highly the teachings of Jesus. In one letter he wrote: “Do you know I have often felt that if we were not Hindus … I should like my people to be Christians?” Rabindranath Tagore is a man described variously as novelist, educator, poet, dramatist, artist, mystic, essayist, and Nobel Prize winner. He was born on May 7, 1861, in Calcutta to a family of considerable wealth. For generations, his ancestors had invested in coal mines and sugar plantations in Eastern India. The Tagores were a progressive family and on their estate often hosted social and cultural activities. As a child he was highly resistant to formal education, later saying: “When I was very young I gave up learning and ran away from my lessons. That saved me, and I owe all that I possess today to that courageous step. I fled classes which instructed, but which did not inspire me, and I gained a sensitivity toward life and nature.” His father provided his son with tutors who gave him a strong foundation in Bengali, Sanskrit and English as well as music and literature. However, being an educational vagabond, he never received a graduation diploma from any scholastic institution. His mother died when he was 13 and Tagore rarely saw his father. Parenting was done largely by servants and extended family members. At the time, upper class Indian families provided their children with an English education, so Tagore was sent (1878-1880) off to England where he enrolled at University College, London, studying law. Again, Tagore was resistant to formal education and did not

complete a degree. At the age of 22 he married Bhabatarini Devi (1883) by whom he had five children. Upon marriage, Tagore reluctantly accepted his father’s offer to manage a family business at Shilaidah in East Bengal. Though he disdained this task, it proved to be formative as he witnessed and became intrigued with the pastoral life of workers on and around the family estate. He observed carefully people working rice fields and others fishing with nets. Tagore enjoyed visiting village school children. This became a prolific period of writing, during which he produced several works, including Chitra: A Play in One Act (1896), The Ideal One (poetry, 1890) and The Golden Boat (poetry, 1894). Little by little, Tagore was establishing himself as a widely read and highly regarded writer in India. In 1902, tragedy struck Tagore with the death of his beloved wife followed by his youngest son. Not surprisingly, death and loss became dominant themes in his writing. During this time, Tagore also founded a school on part of the family estate — Visva-Bharati University. Modeled after Indian ashrams, Tagore’s educational vision emphasized learning in natural (outdoor) settings, avoiding learning by rote and memorization. His school was an open air university. Today it is one of India’s most well-respected institutions of higher learning. Among its notable graduates was Indira Gandhi who would go on to become Prime Minister of India and Nobel laureate Amartya Sen. In 1910, Tagore wrote Gitanjali: Song Offerings. It is a collection of Tagore’s devotional poems expressing spiritual adoration for God and contemplation of God’s many blessings. For Westerners, they resembled the Psalms of the Old Testament. The themes resonate with

people of all faiths because of their spiritual sincerity and beauty. Like the writers of the Psalms, Tagore is able to put his spiritual experiences into words, which are not only attractive and compelling, but with which they can deeply identify. One example is from The Little Flute: Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure. This frail vessel thou emptiest again and again, and fillest it ever with fresh life. This little flute of a reed thou hast carried over hills and dales, and hast breathed through it melodies eternally new. At the immortal touch of thy hands my little heart loses its limits in joy and gives birth to utterance ineffable. Thy infinite gifts come to me only on these very small hands of mine. Ages pass, and still thou pourest, and still there is room to fill. During a dark night of his own soul, Tagore penned these stanzas in Gitanjali: Art Thou abroad on this stormy night on thy journey of love, my friend? The sky groans like one in despair. I have no sleep tonight. Ever and again I open my door and look out on the darkness, my friend. I can see nothing before me. I wonder where lies they path! By what dim shore of the ink-black river, by what far edge of the frowning forest, through what mazy depth of gloom art thou threading thy course to come to me, my friend?

Quickly, Gitanjali became available in other translations and became widely read by Europeans resulting in Swedish Academy awarding Tagore the 1913 Nobel Prize For Literature. Two years later he was knighted by King George V, but renounced it in 1919 as a protest against the Massacre of Amritsar, in which British troops killed nearly 400 Indian demonstrators, according to the British government’s own admission. The power of Gitanjali came from Tagore’s personal experience of God. Edward J. Thompson, PhD, a biographer of Tagore, wrote: “What matters in (Tagore) is … his personal experience of God. Of the depth and sincerity of this no one who has read Gitanjali can doubt. God is strangely close to his thought. He is often more theistic than any Western theist….. God becomes more personalized for him, the Indian, in the most intimate, individual fashion, than He does for the ordinary Christian…. I can only assume that he found it so in personal experience, that neither flesh nor blood revealed to to him but our Father in Heaven.” At the beginning of the 20th century, Indians began resisting British rule. Tagore joined the National movement. However, when members began to engage in violence, Tagore withdrew his membership. For the remainder of his life he would denounce aggressive nationalism and patriotism. In fact, he viewed nationalism as another form of idolatry, writing: “Even though from childhood I had been taught that idolatry of the nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching, and it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against the education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity.”

Despite misgivings about nationalistic pride, Tagore had a profound appreciation of India’s great spiritual and intellectual legacy, saying: “I love India, not because I cultivate the idolatry of geography, not because I have had the chance to be born in her soil, but because she has saved through tumultuous ages the living words that have issued from the illuminated consciousness of her great sons.” Tagore also supported Gandhi’s freedom struggle. In fact, it was Tagore who gave Gandhi the title “Mahatma,” meaning “great soul.” In a speech honoring Gandhi, Tagore said: “So disintegrated and demoralized were our people that many wondered if India could ever rise again by the genius of her own people, until there came on the scene a truly great soul, a great leader of men, in line with the tradition of the greatest sages of old, whom we are today assembled to honor — Mahatma Gandhi. Today no one need despair of the future of the country, for the unconquerable spirit that creates has already been released.” Tagore was especially drawn to Gandhi’s emphasis on ahimsa or non-violence: “Our reverence goes out to the Mahatma whose striving has ever been for truth; who, to the great good fortune of our country at this time of its entry into the new age, has never, for the sake of immediate results, advised of condoned any departure from the standard of universal morality. He has shown the way how, without wholesale massacre, freedom may be won.” Though Tagore kept a distance from Indian nationalists, he did put his literary talents on the side of those seeking independence. He wrote a number of patriotic poems, which were turned into songs, helping mobilize an entire generation of Indians. Tagore became widely recognized as India’s national poet and authored its national anthem “Jana Gana Mana.” Consistently, his poetry conveys a deep-seated spiritual awareness and mysticism. This is evident in his book Fireflies, published in 1928: I touch God in my song as the hill touches the far-away sea with its waterfall…. Love remains a secret even when spoken, for only a lover truly knows that he is loved…. In love I pay my endless debt to thee for what thou art. Tagore drew spiritual inspiration by spending time in nature, observing it carefully, a ritual rooted since his childhood. “We had a small garden beside our house; it was a fairyland to me, where miracles of beauty were of everyday occurrence,” he recalled. “Every morning at an early hour I would run out from my bed to greet the first pink flush of dawn through the trembling leaves of the coconut trees which stood in a line along the garden boundary. The dewdrops glistened as the grass caught the first tremor of the morning breeze. The sky seemed to bring a personal companionship, and my whole body drank in the light and peace of those silent hours. I was anxious never to miss a single morning, because each one was more precious to me than gold to the miser. I had been blessed with that sense of wonder.”

With his emerging fame as a writer, Tagore travelled widely, visiting more than 30 countries on five continents. The travels brought Tagore into contact and conversations with many notable contemporaries including, Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, HG Wells, Ezra Pound and the Irish Poet William Butler Yeats, who would later write the preface to an English version of Gitanjali. By the end of the 1930s Tagore had become world renowned. In1940, the University of Oxford conferred upon him an honorary doctorate citing his innovation in education at Visva-Bharati University as well as his writing. While clearly living a spiritual life, Tagore was critical about aspects of his own Hindu heritage, saying: “Our country is the land of rites and ceremonials, so that we have more faith in worshiping the feet of the priest than the Divinity whom he serves.” On another occasion he observed: “From the solemn gloom of the temple children run out to sit in the dust. God watches them play and forgets the priest.” Healthy most of his life, Tagore became ill in January 1941. During his illness he reflected on the gift of life and pondered whether he had used his talents as effectively as possible: “How little I know of this mighty world! Myriad deeds of men, cities, countries….have remained beyond my awareness. Great is life in this wide Earth and small the corner where my life dwells.” Tagore died on August 7, 1941 at the age of 80. As word of his death spread, many around the world paused, reflected and were comforted by his own words: Death is not extinguishing the light; it is only putting out the lamp because the dawn has come.

|

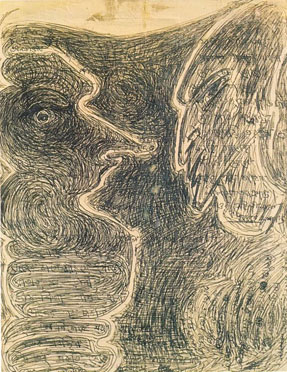

Rabindranath Tagore Mystic Poet