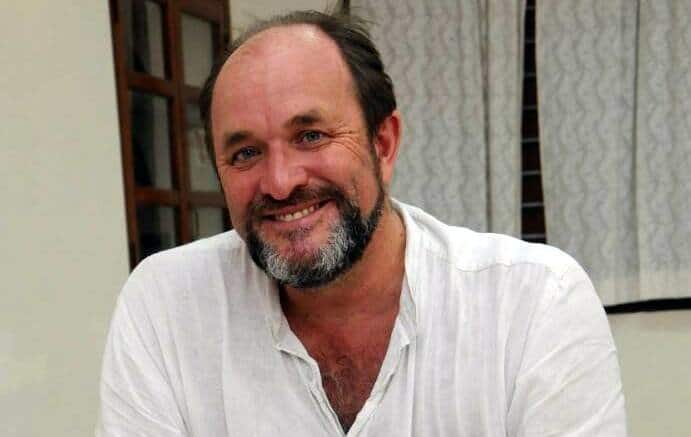

Scottish author and historian William Dalrymple is pleased when he hears that City of Djinns captured the essence of Delhi. It is something that he hears often from his readers about the book on the place he calls his home.

“I have been to Delhi on and off since I was 18, and I have never really left,” Dalrymple tells Little India. “When I moved here, Delhi was a small sarkari town full of Punjabis.”

Now, the city, a bustling metropolitan, has varied stories to tell. City of Djinns is not the only book Dalrymple has authored that takes the reader on a journey through the rugged landscapes of a territory teeming with stories untold. His bibliography lists out a myriad collection of books that balance accounts of travel as well as history with equal ease.

“Travel and history make each other richer. Travel becomes more interesting and transformative when you know the people who have walked there before you and lived their lives in these places,” says the author.

His upcoming book will also have a fair bit of history, taking readers back in time to the 18th century India. Dalrymple notes that the book, which is yet to be titled, will be one of his most ambitious works yet. “All my books so far have been micro-studies. White Mughals is actually based on just a few years in Hyderabad. The Last Mughal covers two years in Delhi,” he says, adding that his new book will talk about events spanning 60 years.

Dalrymple is dreading the initial phase of carving out details for the upcoming book since it covers a vast period of time. “The first few months of writing is always dreadful!,” he says. “It is like an unfit person signing up for a marathon. It is only by the sixth month that I am hoping it will all fall into place like an oiled machine.”

The challenge in this piece, he notes, is to make a clear and cohesive narrative, foregoing minute details such as “skirmishes, campaigns, people changing their minds” and yet writing about everything that is integral to those 60 years that he is covering. Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II is going to be a constant in the narrative. Shah Alam II’’s reign over the crumbling empire had led to the saying: Sultanat-e-Shah Alam, Az Dilli ta Palam (The kingdom of Shah Alam II is from Delhi to Palam, a suburb in the city).

“He starts out as this dashing young man when you begin the book, and by the end of it, he is a winded old man kept as pensioner by the British,” Dalrymple says. “I feel quite bad for him.”

The book, for which Dalrymple spent six years researching and which he will begin to write this April, will be very topical. The book on East India Company would explore the corporate takeover of the state.

“A multi-national corporation replaced the greatest and richest empire India had ever seen — the Mughal Empire. It is quite extraordinary,” he says, mentioning a parliamentary report on the extreme violence that East India Company sanctioned to get its profit margins up.

“Half of the book is not about the company versus India or the Mughals, it’s about the company against the British government — a struggle which goes on today in every legislature between lobbying groups that represent corporate interests. It was the corporates who brought Modi to power with their massive ad campaigns and all the sums of money that was given to the BJP for the last election. It explores the relationship between the power of the state and the power of the corporation — a story of our time,” he elaborates.

However, when it comes to India, the 52-year-old writer is an optimist. He talks about writing pieces on religion, beliefs and practices from an objective standpoint. How does he write about them in such acute detail without judgement creeping in?

“Well this is a cliche, it is about show rather than tell, present rather than judge. You need to be able to show the point of view of the participants of both sides of the conflict,” he says, talking about how in Nine Lives, one of his earlier books, you are able to sympathize and empathize with the characters, even if their beliefs may be abhorrent to you.

Dalrymple rues the poorly-written historical accounts that are taught in the most colorless fashion in India. “So often you see amazing research written in horrible language. That need not be the case.”

He cites the example of his favorite book of a historical account, The Fall of Constantinople 1453 by Steven Runciman. “He is fantastic! Such detailed accounts written in gorgeous prose.”

The Fall of Constantinople 1453 is also the model for one of his own historical works — that he has a soft spot for —The Last Mughal. The trilogy of The Last Mughal, White Mughals, and The Return of the King effectively form an ongoing narrative for his new book based on the East India Company.

Dalrymple, who is one of the curators of the Jaipur Literature Festival, is known for his humorous side, which he displays at the mention of the popular event. “Very few people refuse us. We give very good parties!,” he quips.

He also drops a tiny teaser about the guest line-up for the next year. “Neil Gaiman is coming,” he says. “Ian McKellan, Hari Kunzru, Orhan Pamuk.”

Dalrymple’s new book is likely to be out by that time too. For literature aficionados across the world, the calendar is marked.