|

You have seen him obliterate corrupt cops and politicians single-handedly, silence the unruly with that powerful baritone and create havoc with those magnificent eyes. He is the sullen anti-hero in ‘Zanjeer’, the idealistic, world-weary police officer in ‘Dev’ and the eccentric alcoholic teacher in ‘Black.’ You have laughed over the incorrigible Anthony Gonsalves of ‘Amar, Akbar, Anthony’ and sighed over the achingly romantic poet hero of ‘Kabhi Kabhi’.

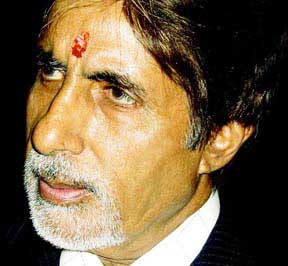

Like swirling stallions on a carnival carousel, these many images of him flit through one’s mind as one goes to meet Amitabh Bachchan in the flesh. In real life, movie stars often seem diminished, smaller, poorer versions of their giant screen personas. Not so Amitabh Bachchan. The towering height that earned him the name of ‘Lambuji’ is there, the deep, brooding eyes and yes, the inimitable voice which can chill and thrill viewers. But how easy is it to reach the real man – does he exist at all, or at least does he reveal himself in interviews? Well, reporters got to see both the man and the myth almost wall to wall with his 12 film retrospective at the Lincoln Center, a press conference, one on one interviews and a 2 hour Q and A. with Richard Pena at Alice Tully Hall. Impeccably dressed, with his hair tinged auburn and his trademark white goatee, he answered the questions succinctly, knowledgably. Asked why Hindi films hadn’t made more of an impact on the west, he responded that the gap was in the marketing: “The west and particularly Hollywood have been masters in how to market their product and that is why they are so good and so efficient and so visible. You must understand that the Hindi film industry doesn’t work entirely in a corporate fashion, unlike Hollywood. “We are still a very individualistic industry and individuals operate and have their own culture, and their own ideas on how they should make films and manage them. Obviously this leads to a lot of experimentation and perhaps that is why collectively as a big force we are unable to market ourselves.” He also felt it would be useful to collaborate with Hollywood, which has a system and pattern that should be emulated. ” We know they have their own distribution and individual theater network. Our request would be to give us permission, give us space so that films from our part of the world can also find exhibition in their theater chains. I’m sure that somewhere down the line something positive will work out.” Would he ever return to politics, he said emphatically, “No – I don’t know politics. I’m not qualified and that’s why I’m out of it.” He said he had entered politics on an emotional note, because of his connections with the Nehru family. “Politics is really a game that I don’t know. I was very out of place and rather than impose my inadequacies on the electorate I thought I’d pull out and just do what I was hopefully good at doing.” Bachchan, who was recently appointed UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, has worked in ad campaigns to create awareness of polio immunizations in India, which helped raise the numbers of mothers taking their children to the polio camps by 100,000. He is also an eloquent spokesperson for the eye bank. “It’s important for people to know that even after they die there is a certain part of their body that can be used for somebody else – Jaya and I felt very strongly about that – and have voluntarily donated our eyes after death.” He also showed flashes of humor; asked about what caused his transition from angry young man to happy old man, he said in that rich voice, ” It was age. when you grow old you can’t play the angry young man anymore, so you play the angry old man, and there are very limited roles an angry old man can do. So you just take what you can get. So you end up playing a patriarch, a retired general, an aging doctor, an alcoholic teacher, who knows.” And at times you even caught glimpses of the real man, his concern for the welfare of people whom he does not know: if a journalist’s tape recorder kept on the podium ran out of tape, he’d call out, “Somebody’s tape just went off!” In one-on-one interviews, while he comes across as a thorough gentleman, he is also withdrawn, aloof, choosing not to reveal himself. The one interview where he’s bared all is in “To Be or Not to Be,” the biographical tome which his wife Jaya published for him for his 60th birthday, a far- reaching interview with the journalist Khalid Mohamed, in which one gets to know that this aloofness is a pattern. Says Mohamed, who has interviewed him many times, “Yet his body posture, surprisingly laid back in a swivel chair, has not altered. In most interviews, like most loners, he discloses as much as he wants to …yet he scatters tantalizing truths between the quotes-unquotes.” Bachchan himself admitted to Mohamed: “When you become a public figure, there’s a natural curbing of your emotions and your behavior. You tend to compartmentalize yourself. You internalize everything you see and observe. You convert it into your craft. “Perhaps that’s why an actor longs to be alone after he’s finished a day’s work at the studio. He wants to stop observing. Stop ticking around the clock. Perhaps that’s why I’m not so keen to keep kicking up my legs, I’d rather be with myself than entertain 20 people who expect me to behave the way I do on screen.” And so it was with this reporter; Bachchan is polite but distant. Anthony Gonsalves, jumping out of a giant egg in tuxedo and top hat, he’s not! He’s not a barrel of laughs, but sitting back with hooded eyes, so that you have to bend forward and try to engage him. The answers are short, often dead-ends. All this recognition for him and for Hindi films, why did he think it was happening now at this time and place? Did he think there might come a time when the film industry would be entirely global with stars from here and there acting in the same movie? “It’s quite possible, yes. There is a possibility of joint productions, sharing of artists, ideas, technologies.” ” From a very early age in school you get involved in school plays and that persisted when I went to college and university. After that when I was working as an executive in Calcutta I came across an advertisement for young men to pursue a career in films. Just for a laugh I entered and was rejected in the preliminaries. I ended up in Bombay. I’m not a trained actor, I was never trained. Once I left my job I had the desire to make it in films.” Was there any really challenging role that he’d like to do, something he could sink his teeth into? “I hope there is something. I don’t know what it is.” The country had come to a literal standstill when he was injured. Was there a time he had felt connected with some of the fans? “Every day, almost. Every day you get moved by some little gesture of people who’ve loved and admired your work. Obviously there was the time when I was sick, the amount of prayers and good wishes that came up from the people, people undergoing personal penance for my sake.” For an actor to succeed or for a movie to click rests on the fans. He’s on that huge, huge screen and there are millions watching. Did he feel any connection between himself and them? What’s a typical day for him like in Bombay? His answer was short, almost minimalist. “Get up in the morning, go to work, come back, go to sleep.” So it’s just like anybody else’s life? “Yes, it is. Others go to the office, I go to the studios. I work out in the gymnasium” People imagine there must be a lot of glamour in his life. “Well, come and visit us on the sets and you’ll find out.” Does it take a lot of hard work? “Of course it does. We all know what the whole process of filmmaking is all about. It takes a lot of hard work. It takes many agencies, many departments and the talents of numerous people goes into creating a moment of joy and entertainment. So yes, it’s a lot of hard work.” What gives him the greatest joy in his life – adulation probably isn’t it. “Being with the family, being with the grandchildren.” So it’s something so universal, in the end it boils down to that? Is there a big distance between being an actor and an ordinary man? “It’s a job. You finish a job, you leave your job in the studios and you come home, just like an ordinary person.” It was then that we seemed to connect, as he made eye contact and we were just two regular people sitting across from each other. Asked about his charity work, he shrugged, “Everyone does charity, whatever is good for mankind.” And how would he like to be remembered? His answer was simple, direct and seemed to give a glimpse of what he really was all about. He said quietly: “As a good human being.” |

Man And Myth