|

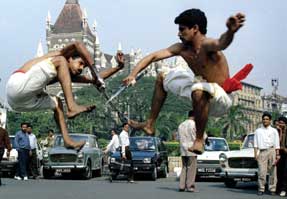

Just after dawn, Sajith Kumar S.S. joins a handful of men and boys in the heart of the bustling southern Indian city of Trivandrum to practice a rare, indigenous martial art once banned by British colonizers to the point of near extinction. After covering their lean brown bodies with oil and clad only in loincloths, the men go through a graceful sequence of warm-up exercises, then challenging postures and movements mimicking wild animal forms. It’s an inspiring demonstration of the raw power and sinuous strength of the lion, elephant, horse, cat, snake, rooster, wild boar and peacock. Kalarippayat, one of the oldest and unique forms of physical and martial training derived from the ancient Indian science of warfare and influenced by Hinduism, reached its peak between the 12th and 16th centuries in the state of Kerala.

At the time, Kerala was divided into feuding principalities and Kalarippayat was practiced in a specially designed arena known as a kalari. It became a key part of cultural education for young men who were often called upon to defend their territory. Although considered a martial art complete with a distinctive set of weaponry, “this was (also) part of the national sport at that time … a social institution, a physical culture form combining spirituality, self discipline, body training, some elements of yoga and mental training, and this was compulsory for every youth at the time,” said Sathya Narayanan director and Gurukkal of the C.V.N Kalari Sangham in Trivandrum, where the men were training. Narayanan’s grandfather, C.V. Narayanan Nair pioneered to preserve the martial art form after extensive research. The C.V.N. Kalari was established in 1956 in his memory and 30 now exist throughout Kerala, all using the same lineage style. Like Gurukkal of the kalari, Narayanan, 44, plays the traditional dual role of martial arts master and physician trained in a special system of medicine similar to the ancient Indian science of Ayurveda, which uses herbs. However, his expertise has more to do with the treatment of orthopaedic disorders such as fractures, sprains and other injuries. “Why? Because as the practitioners progressed in the study, they could specialize in weapons, and they became the source for the soldiers of the (indigenous) army at that time,” Narayanan said. The British banned Kalarippayat for about 70 years until a relaxation of laws allowed it to be practiced again on a limited scale in the early 20th century. But “They didn’t allow any warriors to be trained. That was prohibited,” said Narayanan. During the advanced stages of the art, students engage in battles using wooden and metal weapons. The kalari, built below ground level and with an earthen floor and a thatched roof, has a unique tropical architecture void of fans or air conditioners and its natural ventilation system prevents wind from entering. This helps to create a humid, cocoon-like environment that keeps practitioners warm during the cool monsoon season and cool during hot months. It measures 83 square meters and is about 6.40 meters high.

Ideally students, including girls, begin training at the age of eight. However, Narayanan said most Indian females drop out after puberty. Even Indian boys do not practice the art widely, but it does attract Western martial arts students and scholars interested in ancient cultures. “Because it is hard to practice. It is not easy to learn. The process is long, and it demands a certain amount of discipline. So it is difficult, and the youngsters nowadays also don’t have the time also for that kind of thing,” said Narayanan. The discipline is about balance and suppleness more than endurance. So certain body types lend themselves better to achieving a beautiful lithe movement. But it also requires tremendous mental focus and concentration and the student must demonstrate the potential to develop, said Kalarippayat instructor Rajasekharan Nair, who has spent 36 years training and teaching at the C.V.N. Kalari. The 50-year-old, who works as a government administrator at a science research institute, could easily be mistaken for a man in his late 30s or early 40s. With the increased popularity of yoga in the West, many foreigners have become attracted to Kalarippayat. However, yoga requires the use of the body to achieve a state of mind, mainly through activating the endocrine system, Narayanan said. Kalarippayat “is a more dynamic science that works predominantly with the spine and neurological system as you try to connect your mind to the body through the spinal column,” he added describing the process as “a good amount of psycho-physical activity.” Kumar showed an unusually high proficiency in the art and dreams of making his livelihood from it and spoke openly about how it has enabled him to control his anger. “Before I began to practice about five years ago, I was an angry person. I may still be angry, but I practice so hard, sincerely hard until the anger leaves me,” he said. Kumar was among a small group of C.V.N. Kalali practitioners who were recently invited to Shainghai, China, by renowned martial arts expert Jackie Chan to demonstrate their skills in a Chinese-English language film entitled The Myth part of which was set in India. (DPA) |

Kalarippayat Anyone?