From an unopened tin of Indian tea that was packed for an Antarctic expedition in 1901, to a transit survey instrument used in the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, or the world’s oldest Sanskrit manuscript that is more than one thousand years old, a significant part of India is boxed and preserved in British libraries and museums. And this is the Indian heritage that Cambridge University’s ‘India Unboxed series’ presents.

“Cambridge has eight museums with objects of utmost importance and India Unboxed was an opportunity for us to showcase these objects to the world,” Malvika Anderson, the cultural programmer for the University of Cambridge Museums, told Little India. “Not everybody can come to our museums and have a look at these significant objects, but films are a great way to take these things to the world,” she adds about the project, which is a part of the UK-India Year of Culture 2017.

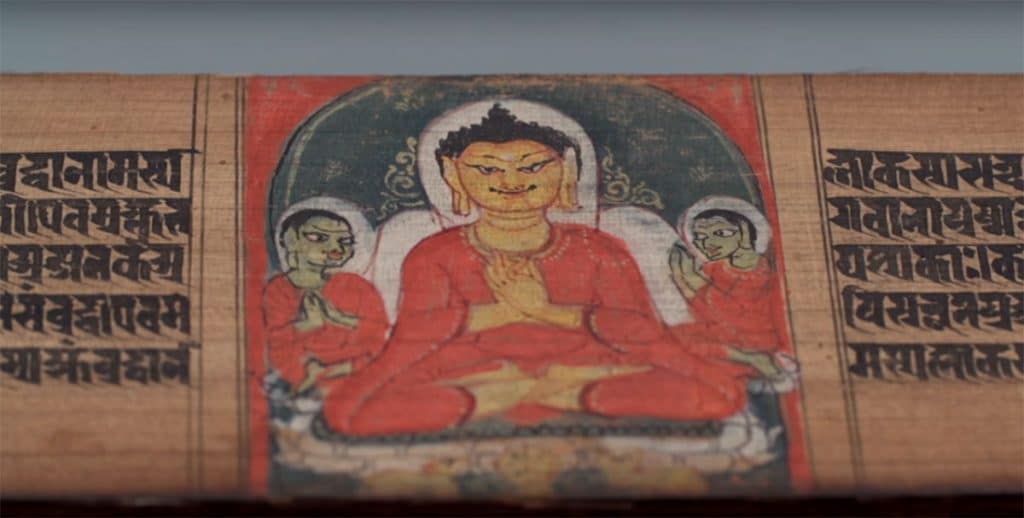

Founded in 1209, the Cambridge University has a large number of India-related objects. One of the films in the series shows the world’s oldest illustrated Sanskrit manuscript, which has an equally famous literary title — Ashtasahasrika prajnaparamita or The Perfection of Wisdom in 8000 Lines. The manuscript ‘signifies the formal introduction to Buddhist thought’.

“To this day, 1,000 years on, the palm leaf manuscripts are still helping to further research on the intellectual traditions, religious cults, literature and political ideas of South Asia,” says Craig Jamieson, the keeper of Sanskrit manuscripts at Cambridge University Library.

India Unboxed has a series of films and exhibitions on offer. The idea of the year-long project was conceived in December last year, after which several teams at the university got involved to discuss various aspects. The most crucial was to select the 10 best items that could tell the story of India to the world.

“The brief was very simple. We wanted to highlight objects that have an interesting story to tell about India. Items that have not been showcased widely or are usually difficult to access. For example, the manuscript showcased in the first film is very old, delicate and rare and it is not easy to exhibit these items regularly.”

The films not just explain what these items are but also how they landed at Cambridge University.

For example, it talks about a meteorite that landed in Dharamsala in the mid-nineteenth century and is currently preserved at Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences.

“British scientists were keen to study the meteorite and when they were planning for it to be brought to UK, everybody thought it would be really hot and arrangements were made to cope with that. However, it was found to be extremely cold. So there is a fascinating story of how it was brought to UK, that you will get to know through the film.”

Among Anderson’s personal favorite is how the story of Greek hero Herakles (or Hercules, to the Romans) connects to India through a three-metre tall sculpture of him, which is one of the oldest plaster casts in the collection of the Museum. The cast has a string of pearls around its neck and “unlocks a world of imagined – and actual – connections between the ancient Mediterranean and South Asia”, according to Dr Hannah Price from the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge.

India Unboxed has further opened the discussion about renowned British museums being prosperous at the cost of wealth from its colonies, and the social, political, and moral implications of such exhibitions.

“We need to be open about these conversations,” says Anderson, adding that we should talk about the legacies and should be open to critique them. “It’s our history. World over museums are now adding on to the political discussions. There is a whole drive of decolonizing museums.”

So if you want to know more about a Naga head-hunter’s trophy or see some very early video footage of India from the archives of the Centre of South Asian Studies, the India Unboxed series is not to be missed.