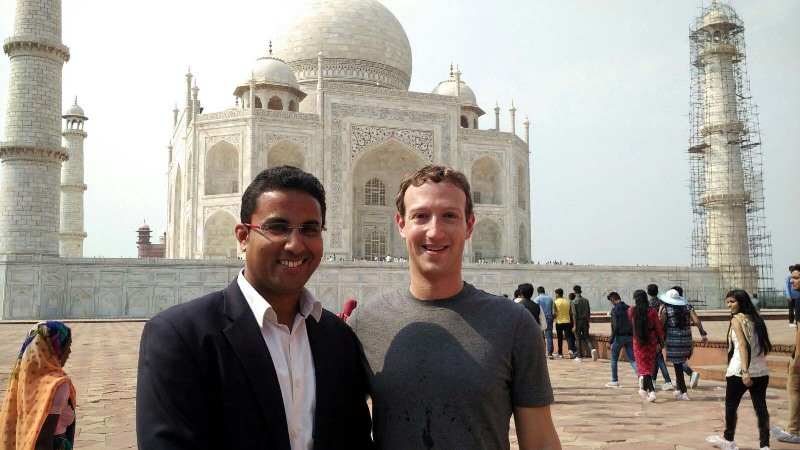

When Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg visited India late last year, he made the mandatory trip to the Taj Mahal in Agra. Almost every foreign visitor to the subcontinent does so; the late Princess Diana had posed alone before the mausoleum when the British royal couple came to India in 1992. A few months later, she and Prince Charles separated.

Zuckerberg also had himself photographed alone at the Taj. He posted the photograph on his Facebook page, accompanied by the comment: “It is even more stunning than I expected.”

Today, a few months later, Zuckerberg finds himself estranged from his Indian constituency. His Free Basics initiative has been banned by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI). Zuckerberg’s dream of being a pivotal part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Digital India program has received a severe setback. And his target of “the next one billion” Facebook users — the first one billion was reached on August 24, 2015 — may have been postponed by months, if not years. (The first one billion is the number of people who logged on to Facebook on that day. It is different from the usually quoted monthly active users, which stood at 1.59 billion on December 31, 2015.)

Considering the outpouring of support for the TRAI ruling in the Indian media and among opinion leaders, it may appear that the decision was inevitable. But it hasn’t always been so. There were some protests from technology experts when Internet.org was unveiled in 2013 as a program that would provide limited access to the Internet for free via the Facebook platform. There was more criticism when it was rebranded Free Basics in September 2015. But issues such as net neutrality were barely understood by the man on the street.

Concept of Net Neutrality

“The concept of net neutrality encapsulates the absence of any form of discrimination for net users including imposition of differential charges for accessing Internet content,” says Abhilekh Verma, partner at law firm Khaitan & Co. “While the argument favoring neutrality of the Internet is an important one, it is also important to note that, in India, Internet penetration leaves a lot to be desired.” Adds Vidya S. Nath, research director (digital media) at growth partnership company Frost & Sullivan: “TRAI’s verdict in favor of net neutrality in India is a reflection of what the majority of Indian consumers want. [But] while it sets the tone of consumer expectations in India, it also threatens to slow down the government’s vision of a Digital India.”

Sen notes that if Facebook and its content partners “fail to offer useful content to users, then such a service will either fail or be forced to become more inclusive as a platform. One way to think about Free Basics is to use the analogy of 1-800 toll-free numbers in the telephone networks that allow businesses to subsidize users’ access cost. The principle of zero rating is the same mechanism now being realized in the context of data services.”

Colossal Blunder

“I am surprised that any country would be dumb enough to homogenize the Internet with no evidence of any benefit,” says Gerald Faulhaber, Wharton professor emeritus of business economics and public policy. “I’m afraid India has made a colossal economic blunder.

“I am not now and never have been a fan of network neutrality,” Faulhaber continues. “To me and many others in Internet space, it has been a solution looking for a problem. There is no evidence that such a problem exists, but here we are regulating the Internet — just like we regulated the old monopoly telephone system — with no evidence that there is a market failure that would justify such regulation. Claims that Facebook’s Free Basics violates net neutrality may well be true, but if so that is simply evidence of how silly and anti-consumer net neutrality really is. Throughout the entire economy, all firms offer pricing and quantity discounts, special deals for long-time customers and/or not-well-off customers; it is perfectly accepted in virtually all businesses, and is part of how firms differentiate themselves from each other. It is an absolutely essential part of competition.”

Faulhaber maintains that in the cases mentioned, customers can choose to get the Free Basics service or the full service, so customers have more choices. “In real life, only governments offer one-size-fits-all services: take it or leave it,” he says. “To force the Internet into this straightjacket is a disaster, to my mind, especially for poor people who otherwise would not have bought Internet services at all. How anyone can think that forcing less choice on customers, and disadvantaging the poor, is a good idea is beyond me.”

According to Faulhaber, “It is claimed that such deals will discriminate against new entrants; this claim is made without any empirical proof whatsoever. It is quite unlikely to be true. New content entrants must usually differentiate themselves from incumbents to be successful, and doing a deal with ISPs (Internet Service Providers) to help differentiate is a great opportunity. Cutting this off, and forcing new entrants to offer the same plain-vanilla service as everyone else, is a recipe for service stagnation and innovation suppression. [However], this may work politically in India, which has a long history of central government control of the economy.”

Digital Apartheid?

Faulhaber’s views are widely shared by the Western media in sharp contrast to the opinion in India. “TRAI lets down millions by saying no to Free Basics,” notes The Huffington Post. “Digital apartheid,” counters the Indian media. “Internet.org was their earlier attempt at doing this,” writes venture capitalist Mahesh Murthy in a Linkedin post. “We’d pointed out even the name was a lie, as it was neither the Internet that was offered, nor was it done on a non-profit basis that dot orgs typically use. So they’ve changed the name to Free Basics and have come back to try shove it down our throats again. Same poison, new bottle but with a big ad campaign….”

It’s the ad campaign estimated to have cost around Rs. 300 crore ($44 million) that seems to have turned opinion against Facebook and Free Basics. “Support a connected India,” said the two-page newspaper ads. Business daily The Economic Times quoted Futurebrands India CEO Santosh Desai: “It was a naked show of muscle power. It’s fair to say it was a mishandled campaign for a company that’s trying to launch a new initiative.” There were numerous complaints filed with the Advertising Standards Council of India.

Simultaneously, in ham-handed PR efforts, the social media giant asked its user base in India — 125 million at last count — to email the TRAI that they supported Free Basics and “digital equality” for India. In a consultancy paper, TRAI had sought the views of the public on net neutrality. As the responses rolled in, all on the same template, TRAI was not amused. In a letter to Ankhi Das, director (public policy), Facebook India, the regulator wrote: The Facebook exercise “has the flavor of reducing a meaningful consultative exercise designed to produce informed and transparent decisions into a crudely majoritarian and orchestrated opinion poll.”

Muscle power… crudely majoritarian… same poison and, to top it all, antagonizing the regulator — the folks at Menlo Park appeared to make every mistake in the book. Zuckerberg had met Modi twice to sell the idea of Facebook partnering the country in the latter’s vision of a Digital India; he may have taken his eye off the ball. And, after all, Free Basics had captured most of the underdeveloped world: its reach extends to 38 countries, the lion’s share in Africa.

“The Indian population is deeply skeptical of hidden fees and other malpractices of their own cellular network companies with whom Facebook would have partnered,” says Sen. “Free Basics was viewed as a nefarious collaboration between a large social network, network providers and the regulators, designed to reduce competition and create ‘walled gardens’ in the Internet. Even if such a perception was misguided, it is ultimately Facebook’s failure to manage its public relations.”

“The issue is not black or white,” says Kartik Hosanagar, Wharton professor of operations, information and decisions. “There is no denying its potential to bring in masses online. At the same time, it is clearly anti-competitive. So the issue is nuanced. Weighing the pros and cons, I am supportive. Some connectivity is better than no connectivity. That said, I don’t think the long-term solution is to have a walled garden. So, while I am personally supportive of Free Basics, I understand TRAI’s decision. Facebook should have adopted the Android approach of providing an open mobile OS to manufacturers but pushing Google products through partnerships with carriers and some original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). In a similar way, Facebook could have provided a truly open service but pushed Facebook products through partnerships. That would neither violate net neutrality nor be criticized as a walled garden. But it would have been strategic for Facebook.”

Breaking Barriers

“While we’re disappointed with today’s decision, I want to personally communicate that we are committed to keep working to break down barriers to connectivity in India and around the world,” said Zuckerberg in a Facebook post. “Internet.org has many initiatives, and we will keep working until everyone has access to the Internet…. Connecting India is an important goal we won’t give up on, because more than a billion people in India don’t have access to the Internet. We know that connecting them can help lift people out of poverty, create millions of jobs and spread education opportunities. We care about these people, and that’s why we’re so committed to connecting them.”

End of story, one would have thought. But another chapter was to follow more contentious than the first. After the TRAI ruling, Facebook director and Silicon Valley venture capitalist Marc Andreessen tweeted: “Anti-colonialism has been economically catastrophic for the Indian people for decades. Why stop now?”

Colonialism is still a sensitive issue for most Indians. In the 1700s, the country’s GDP was 24.4% of world GDP. After more than two centuries of legalized pillage (under British rule), it had shrunk to 4.2% at the time of Independence in 1947. Tweeted Murthy: “Now @facebook board director @pmarca [Andreessen] suggests being colonized was good for India and we should’ve let Fb [Facebook] do so.” Andreessen subsequently deleted the tweet and withdrew from the debate: “For the record, I am opposed to colonialism in any country.” Zuckerberg disowned Andreessen. “I want to respond to Marc Andreessen’s comments about India yesterday. I found the comments deeply upsetting, and they do not represent the way Facebook or I think at all.”

Social Media Explodes

Several Indians found the comments deeply upsetting, too, and social media was filled with criticism. This was also because after a lot of mind-numbing techspeak on net neutrality, colonialism was something everybody could understand. The TRAI became a hero and the ruling was interpreted as standing up to the neo-colonizers.

“Andreessen’s tweet was in poor taste and demonstrates a lack of knowledge regarding the matter,” says Sen. “Anti-colonial feeling was not the reason for the public’s opposition to Free Basics in India; the real reason was simply that a large portion of the Indian population did not buy Facebook’s pitch that Free Basics was an altruistic venture.”

Sen doesn’t see the TRAI as the hero keeping out the MNC barbarians at the gate. “TRAI’s actions during this net neutrality debate deserve much criticism,” he says.

“Its request for comments from the public goes to shows how apathetic the Indian government is towards the masses who were supposed to be the real beneficiaries of the Free Basics initiative. The online petitioners to TRAI clearly don’t represent the market segment that Free Basics was designed for.”

“Zuckerberg and the leadership at Facebook must recognize the need to convince people in India and elsewhere that their Internet.org initiatives are more than thinly veiled efforts to expand the global market share of an American company,” says Kevin Werbach, Wharton professor of legal studies and business ethics. “Andreessen’s unfortunate tweet shows one of the problems with what can be called the Silicon Valley worldview. Technology startups and their advocates in the U.S. view themselves as innovating outside the bounds of geography, but the rest of the world often sees them as advancing American ideals and promoting American hegemony. It’s difficult for the Silicon Valley community to appreciate this, because they so often position themselves in opposition to governments in the U.S., as in the debates over surveillance and regulation of new services like Uber. There is a controversy about zero rating in the U.S., but it doesn’t involve the concerns about digital colonialism that were prominent in India.”

It won’t be hyperbole, however, to say that Facebook has had a torrid time in India. On Monday came the TRAI ruling. On Tuesday, Andreessen made his infamous tweet about the virtues of colonialism. On Wednesday, an “ill-informed” Andreessen and a “deeply-upset” Zuckerberg made several attempts to douse the fires.

Recently, the company announced that it was officially withdrawing Free Basics from India. On Friday, Kirthiga Reddy, Facebook India managing director and public face, said she was stepping down; the company’s first employee in India was planning to take her last bow. (For the record, Facebook said she was going to relocate to the company’s Menlo Park headquarters over the next six to 12 months and that she had had nothing to do with Free Basics.)

In India, Facebook has clearly lost face in more ways than one.