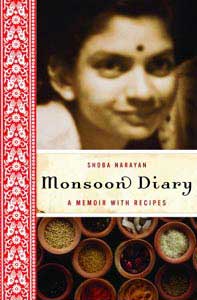

| Monsoon Diary A Memoir With Recipes by Shobha Narayan Villard Books, New York, N. Y. 2003, pp. 223. Shobha Narayan is no stranger to the readers of Little India. Her memories of a cross country road trip from New York to Los Angeles that she took with husband and her grandmother, a strict vegetarian, was published in the magazine a few years back and resonated with many readers. How many of us have not stood glumly in the midst of yet another bustling reststop food court debating between the indigestion quotient of eating (yet again) a slice of pizza or French (Oops! Should that be Freedom?) fries or going the healthy but tasteless route and buying a plastic box of soggy salad?

In her essay, Narayan humorously related her grandmother’s gradual acceptance of “outside” food and her serendipitous discovery of edible items, among them : French crueller from Dunkin Donuts as a substitute for jilebi and the chain’s coffee as a perfect step-in for filter coffee; and mixing ketchup, from Wendy’s, with hot water to make rasam that she poured over the plain white rice that Chinese restuarants throw in with a regular order. It was to become a favorite meal that sustained her all the way to California. This time around, Narayan has brought out a memoir on her personal journey, from a carefree, indulged childhood in South India, to her college days in Connecticut, leading up to her present life as a mother and wife in New York City, all laced together with mouthwatering descriptions of home-cooked Inji-curry, Rasam, Pav-bhaji, Idlis, Potato Masala, Pongal, and Upma. The rich, nutty scent of ghee ( a detailed recipe is given on page eight) mingled with creamy coconut milk and tangy tamarind seems to waft through the chapters and it is very hard not to give into the urge to drive to the nearest Udipi and order the special thali with all the works. A winner of the 2001 M.F. K. Fisher Award for Distinguishedº writing (Narayan won it for her story, “The God of Small Feasts,” which orginally appeared in Gourmet magazine), and a frequent contributor to NPR’s All Things Considered, Narayan retraces her personal history by examining the role food plays in her family’s daily rituals. Gifted with a sharp eye and a understated style of writing, Narayan brings alive the people and place that populated her life with with frank, gentle humor. One of the most delectable chapters in the book is a description of travelling on the train in India and encountering food and people from around the country. During her trips Narayan gets to taste kadi from a Marwari matron, rajma from a Punjabi family, and rosgollas and sandesh from another Bengali family – all fellow passengers sharing their home-cooked meals. As the trains wind through different states, there is not only a steady stream of vendors offering a range of snacks and coffee or tea but also the regional specialites offered by each station: different kinds of mangoes in Renigunta, oranges in Nagpur, pedas in Agra, and yogurt served in tiny terracotta pots in Delhi. Each little treat is like snatching little bits and pieces of India, brief visits to each region, before running back to one’s seat to continue the journey. Narayan’s narrative is full of hreferences to the cultural nuances of her upbringing in South India, beginning with the first food she ever ate: rice and ghee at six months old, when she was fed a mouthful of it in a formal ceremony called, choru-unnal (rice-eating), at a ceremony held at the famous Guruvayur temple in Kerala.º This is a very traditional event that celebrates the first taste of solid food by an infant and it is usually held at a well-known temple where grandparents and uncle and aunts congregate to take their turn and place bits of mushy rice into the child’s mouth, while a priest stands by reciting mantras. In a typically witty observation, Narayan muses that because most Indians do not understand Sanskrit, the meaning of the mantras are obscure. “It is presumed that they will nudge the baby into a lifetime of healthy eating. This particular presumption must be wrong, for I know of no Indian child with good eating habits.” Narayan spends the first years of her life with her pious Hindu grandparents in Coimbatore, a small town in the foothills of the Blue Mountains. Here she picks up the rhythms of a traditional Tamilian household: seeing her grandfather doing the tharpanam (ancestor worship) every new-moon day, eating pongal ( rice and split mung dal spiced with ginger, pepper and turmeric) every time the seasons changed andº hunkering down with the women of the household on bamboo mats every afternoon to watch them chew betel leaves and make raunchy jokes. Each year, before the monsoon begins, her grandmother sets out to make vatrals, (dried, dehydrated, pickled vegetables) and vadams (wafer-thin rounds of sun-dried rice flour that are deep-fried into crisp fritters) to be eaten during the winter months when fresh vegetables are scarce. The making of these treats is a family activity. On the day the vadams are to to made, the entire household, including the maid servant and four-year-old Narayan, are up on the terrace before the sun rises, swiftly spreading spoonfuls of vadam paste on cloth. Her grandmother’s “intent face and rapid, calligraphic movements as she cajoled, rolled, and shaped a simple rice-flour mixture into a delicous treat,” is something that Narayan can still conjure up each time she bites into a vadam or vatral. Narayan goes to live with her parents when she is five,º in a suburb of Madras, and becomes increasingly aware of belonging to the TamBram (short for Tamilian Brahmin) community. Narayan glancingly notes that while the word caste is shunned in India and America, it continues to play “an important part of the way Indians define themselves.” An important defination of being TamBram, for Narayan, is of course, food, specifically, soft idlis and fragrant, filtered coffee. In the Catholic school she goes to in Madras, (Narayan gives us her hilarious version of the Lord’s prayer as she understood it in second grade: “Ah father, Charty Nevin, ah low be thy knee. Thy kin dumb come thy will bidden north cities in heaven…” ), lunch hour is the most anticipated time of the day. Narayan gets to sample the contents of her friends lunch boxes, especially Amina’s, a Muslim girl whose mother makes the most fragrant chicken birayani. Narayan is forbidden to eat meat, so she just picks out the delicious, spice-drenched morsels of rice. She also loves her Syrian Christian friend, Annie’s spicy potato, onion, peas and coconut milk stew, and her Telegu-speaking friend Sheela’s red chilli-spiked mango pickle. Food, Narayan, unwittingly reveals, can be the perfect bridge between religous and linguistic differences For Madras aficianados, Narayan’s descriptions of places and landmarks will revive fond memories. She talks lovingly of breakfast at Woodlands, the cultural talent at the Mardi Gras held every year by the Indian Institute of Technology, the college cafeteria at the Women’s Christian College or WCC, as the locals call it, and shopping with her mother for vegetables in Pondy Bazaar, spices and appalams (fried lentil wafers) at Ambika Appalam Depot, or for lingerie at Naidu Hall, famous for “airy nightgowns made from the softest cotton.” Her mother also offers Narayan insights into the intricacies of South Indian cooking: “Cumin and cardamon are arousing, so eat them only after you get married. Fenugreek tea makes your hair lustrous and increases breast milk, so drink copious amounts when you have babies. Coriander seeds balance and cool fiery summer vegetables. Mustard and sesame seeds heat the body during winter. Asafetida suppresses, cinnamon nourishes, and lentils build muscles.” In spite of her reluctance to stay in the kitchen while her mother lectures her on the niceties of food combinations, Narayan clearly picks up a few skills. When she wants to go to college in America, her uncle throws her a challenge: cook a vegetarian meal for the family. If everyone relishes it, she gets to go. Narayan stuffs and fries okra, slow-cooks tender spinach into a velvety curry, stirs up some tangy rasam and serves it all up with fluffy, separate grains of basmati rice. She wins that challenge hands down. At age 20, she enters Mount Holyoke, Connecticut as a Foreign Fellow, and begins her American journey. She stands in front of the breakfast choices in the cafeteria unable to decide between varieties of breads, pastries, cereals, fruits and milks, feeling the impatience of the others in the line behind her. But soon, her job at the cafeteria opens her palate to the delights of pastas, pizzas, enchiladas, falafel, potato pierogis, and vegetable fried rice. Still, when she needs comfort food, its a tub of yogurt and plain cooked rice that comes to the rescue. She sits cross-legged on her dorm bed, eating balls of the bland, familar food because, “I needed Indian food to ground me.” Later, after her master’s degree is revoked by Memphis State University because the school’s adminstrators don’t approve of the changes that Narayan makes to her thesis, she returns to Madras seeking the solace and support of her family. And she agrees to their suggestion that she have an arranged marriage. Narayan writes of this whole experience with marvellous restraint, conveying the pain of the Memphis experience and the doubts she has about arranged marriages and the ordeal of being inspected with the potential of being rejected. Her parents invite Ram and his parents to a tiffin where they serve the traditional tiffin meal for a boy-meets-girl occasion: sojji (warm, semolina and milk pudding) and bajji (vegetable fritters). Sojji-bajji is such a staple of these prospective meetings that Narayan states the words have come to mean that one is thinking of getting married, as in: “Now that you’re thirty, you’ll probably be eating a lot of sojji-bajji.” Narayan and Ram hit it off and make a match of it after all and the wedding tiffin included carrot halva, saffron-sprinkled sojji, and almond payasam, complemented byº savory vadas with spicy coconut chutney and onion sambar, fluffy idlis, and dollops of upma, all served on shiny banana leaves. As a student in Boston, Narayan once decided to make an ambitious dinner: a dish from every continent, except for Antartica, because she could not find a vegetarian dish from that region.º But the dinner spiced with Japanese, Italian, Ethiopian, and South American ingredients was a disaster. Guests were either allergic to something in the food or each other. In desperation, Narayan found some cream of wheat in the cupboard and rustled up an upma studded with onions, peas, ginger, and green chillies. Everyone polished off their servings, and Narayan was finally granted her wish to make a dish “that would surprise and delight my guests into prayerful silence.” In this well-written, lively, evocative memoir, she has produced a work that is as piquantly entertaining as her rasam recipe. |

Hot Stuff