|

“Unfortunately… he died few minutes ago. (4:55 pm).” Just six words, but what a world of tragedy they enfold. Nabeel Siddiqui, 24, a computer science major who graduated from New Jersey Institute of Technology this summer, suffered brutal neurological injuries and trauma when three juveniles attacked him with a baseball bat on his head at Haxtun Avenue in Orange, NJ, as he got out of his car to deliver a pizza.

The three, a 16-year-old from Woodbridge and a 16-year-old and 17-year-old from Orange, have been charged with aggravated assault, robbery, carjacking, and possession of a weapon. Baseball and pizza. Such quintessentially all-American, joyful symbols. Yet why is it that a baseball bat, which one associates with sportsmanship, Little League innocence and camaraderie, turns into a killing machine when bigots see skin of a different hue? Pizza, that ubiquitous fast food, turns deadly when the deliveryman has an accent or comes from another culture. Back in July, a young Indian graduate student, Saurabh Bhalerao of University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, became a victim of a hate crime in New Bedford, viciously beaten by four men, as he delivered pizza. Another one of just too many tragedies with victimized blue-collar workers. Syed Asif Alam, a New Jersey based systems architect, is a family friend who put up Nabeel Siddiqui when he first came to the United States five years ago. He recalls: “He was a very witty guy, he always had good stories. He was a big fan of music. The last time I talked to him –a day before the attack – he was very excited because he had some job interviews lined up. He had just graduated with a computer science degree and he had a lot of questions.” After the attack, Alam kept the community apprised of Siddiqui’s situation via Internet list serves. The young man never awoke from the coma; never saw the mother who rushed from Pakistan to be by his side. Alam says, “She was totally heartbroken.” It is the fabric of nightmares, to send your only son to America to earn a degree and to have to bring him back in a body bag. “The death of this young man is very symbolic of the violence that immigrant workers face in this country,” says Bhairavi Desai, director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. She cites a survey of 581 drivers in which 24 percent experienced some kind of vandalism of their vehicle, 15 percent were physically threatened, 9 percent were physically harmed and 34 percent were verbally harassed. She adds, “These are extremely high numbers out of just 581 drivers; so imagine the number of incidents given that there are 24,000 active drivers in the industry.” Hate crimes are surely on the rise. The National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium (NAPALC), based in Washington, conducts an annual audit, a comprehensive, non-governmental compilation and analysis of hate crimes nationwide. It is currently preparing its 2002 report. The 2001 figures are telling: 507 bias-motivated hate crimes against Asian-Americans, a 23 percent increase over 2000. NAPALC reported that a large number of hate crimes in the aftermath of Sept. 11, targeted South Asian Americans, and more particularly Sikh Americans, because many wear turbans and beards, similar to the widely publicized image of Osama Bin Laden. According to the FBI, there were 36 victims of anti-Islamic bias in 2000. In 2001, the FBI figure jumped to 554 victims. According to NAPALC, the real figures could be very much higher than the FBI figures because law enforcement agencies do not classify a crime or incident as bias-motivated when there’s only an account from a victim, the perpetrator has not been caught or there are no witnesses. The report sites language barriers, fear of police, fear of retaliation and fear of the INS as other causes of under-reporting hate crimes. Despite the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990, not all hate crimes are counted and documented. In the 1980’s, it was a baseball bat that had shattered the skull of a young Indian, Navroze Mody, as he walked down a street in Jersey City. Have things got better or worse in the past 20 years? “How do you quantify human rights?” asks Desai. “The right to be safe in your society is a matter of a human right. It’s really working class South Asians who get attacked. I know there’s talk about jealousy of the Indians who are upwardly mobile, but it’s the downwardly mobile Indians who face the attacks.” She points out that taxi drivers are 60 times more likely to be killed on the job than any other worker, according to department of labor, followed by store clerks. Gas attendants, construction workers, and delivery persons – these are all professions dominated by black and brown immigrants, who often don’t have the luxury of choice, when it comes to choosing a livelihood: “They are perceived to lack political power so they are seen as more vulnerable.” Desai notes that historically the taxi occupation was far less dangerous when the industry was dominated by Whites: “Before the taxi industry became predominantly composed of immigrants of color, the taxi drivers earned better money, had health benefits and had safer conditions.” The problem of hate crimes is not limited to blue collar professions. Racists do not differentiate between rich and poor immigrants; they are driven – like raging bulls – solely by color? Deepa Iyer, a co-founder of SALT, who was earlier a civil rights attorney with the Department of Justice in Washington, says, “I think it’s a lot of anti-immigrant sentiment, where people say ‘Go back to your country, you don’t belong in our neighborhood.’ So a lot of it has to do with a perception of who’s American, who belongs in this country.” And as anyone living in America today or even flipping through an American newspaper knows, the situation has deteriorated markedly since 9/11 when the World Trade Center attacks created so many new enemies, some real, some perceived. You could be born and brought up in America, may have pledged allegiance to the flag since you were old enough to recite the words, but if you are of a certain color or if your features look remotely Middle Eastern, then all bets are off. You could be Sikh, Hindu or Muslim, but suddenly you are Osama, you are a terrorist and don’t you dare deny it. The aftermath of 9/11 saw a larger tragedy unfold, of Americans turning against Americans, simply because of their skin color or the way they looked. Amardeep Singh Bhalla, one of the founders and legal director of the Sikh Coalition, a civil rights advocacy group, says, “Earlier, the biggest issue the community faced was employment discrimination. After 9/11 that changed in a much-accelerated manner and we’ve had about 300 reports of bias against Sikhs ranging from hate crime to bias-motivated harassment on the street.” Desai too has seen the violence against taxi drivers increase dramatically after 9/11. Her organziation has received scores of incident reports where drivers’ tires were slashed, profanities were carved into their back seats, and cars even set afire. Even though hate crime laws are in the book, according to Desai, prosecutors in New York have almost never brought a case using these laws. “There are many more hate crimes, particularly against South Asians, Muslims and Arabs after 9/11,” says Partha Banerjee, community organizer of New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE): “According to governmental statistics, there was a 1,600 percent rise in hate crime incidents right after 9/11. After that, the incidents came down, but once again have gone up. Most importantly, many hate crimes are not being reported because people are so afraid.” Since 9/11, the newspapers have been replete with stories of violent crimes against people of South Asian descent. Recently a Sikh family returning home in Woodside, NY, was attacked by a group of men yelling “Bin Laden, go back to your home country!” According to Banerjee, NICE put together a strong responsive emergency meeting at which community members showed up and the incident got media attention. He says, “We were able to provide some kind of space of security for the Sikh community in Woodside. Both criminals are at large and in more than two months there has not been a single arrest, which makes the victim communities even more apprehensive about reporting hate crimes and that’s why the numbers reported or given out by the NYPD Hate Crime Task Force or the Mayor’s Office are not correct.” A survey of Muslims, Arabs and South Asians in New York recently released by the New York City Commission on Human Rights found that 69 percent of respondents reported perceived discrimination and bias-related harassment. Almost one-third of incidents involved religious and ethnic insults or physical assaults. Almost a quarter of the respondents reported employment discrimination, alleging that they had been taunted as “Bin Laden” “terroprist” or “Taliban” in the workplace. According to the report very few reported the discrimination, the majority because they felt either that nothing would be done, or because were afraid or uncomfortable reporting the incident. The report found that almost b4 in 5 respondents reported that the events of 9/11 had adversely affected their lives, noting: “A large number of individuals noted that they had altered their behavior or manner od dress so as not to attract notice. For example, they would speak only English in public, cut their hair, shave their beards, wear hats instead of the hijab, or Americanize their names. Many said they were afraid to be in public places, and some said they no longer go out as much or only go out with friends and relatives. … Many spoke of being scared, stared at, initimdated, fearful, alienated, depressed, uncomfortable, cautious, hurt, uneasy, ridiculed, shamed, misunderstood, sad, blamed, insecure, scrutinized and emotionally stress.” As these bashings occur, one realizes that there are many baseball bats – literal and symbolic. Violence pervades our lives and as Desai points out, it includes physical attacks, verbal abuse, political disenfranchisement and economic impoverishment. We are living in violent times, an age of pre-emptive strikes and a seemingly endless war against terror. She questions, “When the President of the United States can bomb a country because he perceives it to be a threat, then what moral authority does that government have to tell the bully on the street that he cannot beat on somebody because he perceives a threat? So we are living in generally very violent times and of course, all the Muslim-bashing and immigrant bashing has created an atmosphere of violence and terror.” Indeed, sometimes it is hard to separate the bias crimes of ignorant bigots and those propogated by governmental policy, such as the mass detentions, raids at work, racial profiling and deportations that have plagued the Muslim community. Says Desai, “People in authority set the standard. The myth is that wealth trickles down, but the reality is that violence trickles down.” The NAPALC audit points out the harsh facts of post 9/11 America, as the Bush Administration targeted Arab and Muslim Americans in the name of homeland security. For example, it notes that the U.S. Department of Justice rounded up and imprisoned over 1,000 individuals of Arab and Muslim backgrounds without charge or allowing them access to attorneys. The Department of Justice also publicly demanded that local police help them pressure 5000 Arab and Muslim immigrants to submit to interrogations and asked universities to turn over confidential files of students with Arab names. Various advocacy and human rights groups have protested these violation of personal rights, and The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) points to the Special Registration program as the worst in a series of counter-productive and increasingly draconian policies implemented in the name of national security. The group cites official figures that over 82,000 people have been interrogated under oath, fingerprinted, and photographed under Special Registration and the government is now trying to deport 13,000 of those individuals. According to AALDEF staff attorney Sin Yen Ling, “I have personally represented scores of individuals and families who are among the thousands whose lives have been destroyed because of Special Registration. It’s been implemented as policy as of last year and there are no signs from the Bush Administration that they are going to end it.” Meanwhile, a fresh batch of individuals face the dread of Special Registration on November 6, 2003, to be photographed, fingerprinted, interrogated, detained and possibly deported. Many of them will have known no other home but America, others will be leaving behind wives, children, jobs, lives left dangling on the Pause button. Yet, isn’t it a Catch-22? Doesn’t the government have an obligation to protect its citizens against what happened on 9/11, to prevent it from ever happening again? Says Desai, “No evidence was ever found. It’s the idea of pre-emptive strikes. It sets moral and political standards that allow for a more violent society. It’s racism. Silence is complicity; when you don’t have people in authority saying this is a crisis, then it’s almost as good as condoning it.” So where do the solutions lie? Says Desai: “The solution lies among the people and it lies in the grassroots because while violence trickles down, change rises up. It’s up to the grassroots organizing to change the balance of power and create safer streets for everybody.” The good news is that scores of organizations have arisen to meet the need and victims can find support. As Iyer observes, “Unfortunate as it was, 9/11 has provided an opportunity for the South Asian community to become a little bit more vocal and visible when it comes to furthering civil rights and human right issues. I don’t think we’ve got to the point where there is a ‘South Asian-American’ consciousness in our community but I think we’re getting there slowly.” There are now many more organizations for victims to turn to from the older organizations such as AALDEF, CAAV and SMART to newer ones like NICE and SALT, organizations where their language is spoken, their point of view embraced. Victims are encouraged not to take bias lying down. Recently Hansdip S. Bindra, a Sikh, filed a landmark lawsuit against Delta Airlines for racial profiling and harassment. He was aided by SMART, founded in 1996, the oldest national Sikh American civil rights organization. While many of the advocacy groups are composed of second generation Asians or South Asians, others are collaboration between second and first generation groups. “Hate crimes are an issue which affects pretty much everybody and one is not insulated from these sorts of incidents just because of one’s economic status or where one lives,” says Iyer. “Although poorer immigrants seem to get the brunt of it, it affects people from across economic lines and class lines because all of us have come from somewhere, all South Asians will feel some identification with ‘Go back where you came from!’ So it’s an argument for people of all economic backgrounds to work together on this issue.” Iyer is currently teaching a class at Columbia University on how South Asian communities have been impacted by 9/11. She says of her students, “It’s a pretty diverse mix and there’s definitely a lot of interest and it’s to Columbia’s credit that they were open to something like that. I think it’s important to have as much discussion and debate over these issues as possible in a variety of contexts.” While many second generation South Asians may be more outspoken because of the security that comes from having American citizenship, they also do have a stronger sense of civic responsibility and civic engagement than the first generation. Says Iyer: “The students that I have are very well versed already in a lot of the issues. They want to engage in these issues and they feel like they have a stake in the country’s future and they want to be a part of that.” The second generationers certainly don’t believe in sitting on their hands: they are willing to march and rally; volunteer with activist organizations; write articles, reports and plays and make videos and films about hate crimes and discrimination. One such film was made recently by Pia Sawhney and Sanjna Singh, graduates of Bryn Mawr College. Out of Status is a short film exploring how in this new world, Muslims have fallen out of status in America, with selective enforcement of existing immigration laws and tough new measures to keep tabs on this community. While making the documentary about detentions, the filmmakers visited several organizations that were working closely with South Asian communities. “We found that not only were South Asians who were victim to new hard line government policies afraid to speak to us on camera,” observes Sawhney, “but the South Asian activists working to counsel them and provide them with legal help and guidance were afraid to speak to us on camera as well! It was telling how the desire to make voices heard was constrained by the fear about how speaking out might jeopardize their own credibility, or perhaps even their own immigration status in the long run.” Yet, slowly, the fear is being overcome as organizations reach out to the victims. NICE, for example, had a very successful town hall meeting in Jackson Heights, NY, and for the first time immigrants came out and spoke about their problems. “People are slowly coming out but it will take a lot more time to provide more confidence to them so that they can come out in larger numbers,” says Banerjee. ” We are very concerned about governmental access and accountability and we try to hold our government officials accountable for the actions that have direct impact on the immigrant community.” One organization that handles cases of bias is The Sikh Coalition. Says Bhalla, “Actually in terms of statistics from January 2001 to Sept 11, 2003 we had a 93 percent increase in the number of complaints we received about discrimination and we believe the reason for that is the ongoing tensions in the Middle East and people assuming that Sikhs are from the Middle East.” He has also noted that about half the cases this year occurred during active hostilities or combat operations in the Persian Gulf. Recently the Sikh Coalition received a call from Harjit Singh Sandu, a cab driver in Seattle who was stopped at a corner when people started yelling, ‘Osama go back to your country!’ and ‘We don’t want you here!’ He tried explaining he was a Sikh, but when he attempted to leave they followed him and started kicking and denting his cab. “Our concern was that the police officers had not noted any of the epithets in the police report,” says Bhalla, “So we wrote to the Bias Crime Co-coordinator of the police department, asking it to be investigated as a bias crime, and the criminals be charged with a bias crime. Asked if he’s hopeful about the future, Bhalla says, “My bottom line belief and the experience I’ve had since 9/11 is that this is a country that’s pretty good with dealing with discrimination issues. I think government agencies are responsive, it’s just incumbent upon the South Asian communities to collectively present our concerns to police, to government and policy makers. We’ve been pretty happy with the bias crime prosecutions that have occurred here. Generally, I think there’s reason to be optimistic as long as on our part we are organizing and presenting our concerns.” The anti-violence mantra has to be organizing, organizing and then some more organizing. As Bhairavi Desai says, “So many drivers said that after the strike was the best interactions they had with the passengers; for the first time the public saw that this was an organized workforce that can fight, that can defend itself. I think it automatically led to greater respect.” But, like a multi-headed hydra, hate crimes have many faces and the newest wrinkle is violence against South Asians by other people of color, often in the schoolyard where young Bangladeshis have been attacked by groups of Latinos or other minorities. It makes one wonder whether one has to start sensitivity training in the crib. Tamina Davar, a young activist, has seen the change in the past decade. “I’m sure that if you ask most South Asians activists, they will agree with me that 10, or even 6 years ago, the rising tide of Asian-American and within that, South-Asian American hate crime was so upsetting and stressful, in part because the media generally hrefused to cover it as important; law enforcement and the judicial system hrefused to believe it often, and because besides AALDEF and CAAAV, no one else was dealing with it.” Now with many more organizations and the added weapons of email, cell-phones and the Internet, things are better and as Davar says, “Especially since 9/11, the media does understand the concept; and there are so many infrastructures and groups that deal with the issues. So now, whenever I hear of a hate crime, whether in Arizona or here, I know and am comfortable that some really wonderful, strong organizations and infrastructures are dealing with it.” “There’s more awareness,” concedes Bhairavi Desai, ” I do think all this organizing, and the civil rights movement of the 60’s and just the different movements down the decades have had an impact. And that’s why fighting the current war is so important because their actions of the past few years are an attempt to take back everything that people have fought for over the past 40 years.” SMART (Sikh Mediawatch and Resource Task Force) The Sikh Coalition New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE) South Asian American Leaders of Tomorrow South Asian Network (SAN) Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities (Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence) DRUM (Desis Rising Up & Moving) |

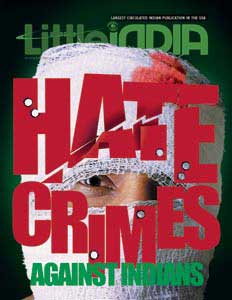

Hate Crimes Against Indians