|

You certainly can’t buy it on eBay. Nor will you find it in a GAP catalog or a Walmart store. Yes, you may pick up the outer trappings at a mall, but you still can’t purchase the actual thing. It is not bottled like Ralph Lauren’s fragrances or packaged in a neat little bag, a la McDonald’s fries. We’re talking of the American identity, that most elusive, maddeningly changeable chameleon which defies description.

Is the Indian immigrant, who left India a quarter century ago but still pores over news from back home, an American? Does he feel an American or a bit of a fraud? And is Hindi an American language? How about samosas and chicken tikka masala: are they all-American foods like burgers and fries? Can a woman of Indian origin, dressed in a sari and bangles, call this land her land? Indian immigrants arrive with so much baggage with them – and we don’t mean the overweight, overloaded suitcases, bursting of masalas and cooking utensils, family albums and wedding saris. There is also the mental baggage that obstructs the leap to that stereotypical “All-American” label. Baseball is the great unifier of America, but what do you do if your heart belongs to cricket? How do you get into American pop culture when it is Bollywood that makes you laugh and cry? How can you be as American as apple pie when you’d rather be eating bhel puri? Where do Indian immigrants fit into this Monopoly board game of the American Dream? When do they get to feel they belong? Is it when they have wads of money? Is it when they snap up hotels and properties that they pass Go? Or is it something much more ephemeral, a sense of comfort, of forming bonds and putting down roots in an alien landscape? In essence, when does an Indian become an American? Ok, half American. Through thick and thin, through the inconvenience of immigration lines and delays, he has stuck with his beloved Indian passport. As he told an interviewer, “No, no, this inconvenience is not a reason to change your nationality. This is not a passport thing. I feel Indian since the day I was born and I will die an Indian.” Will the promise of dual citizenship that the Indian Government has held out for NRIs finally get him to become American? Indeed, ask Indian immigrants about their nationality and the word Indian will definitely feature in any description of who they are, even if they have lived here 30 years, have an American passport and American born children. Then again, there are others who have celebrated when they secured that all elusive green card and thrown joyous parties when they finally got their American citizenship. Yet can citizenship papers change your thinking, your being? Can the Statue of Liberty and The Star Spangled Banner call in the same way to a child who has grown up waving the Indian flag and gotten goose bumps reciting the Indian national anthem? In those days, to leave India was to literally cut yourself off from the homeland. “When I was a 20 year old student just freshly arrived, it would take so long to get those aerogrammes! I would look forward to the blue aerogramme in my students’ mailbox from my parents, but it took so long between the questions I would ask and the responses that came back. “Now it’s all e-mail, and the sense of border-isolation is less real and less traumatic. Everyone here has lots of relatives who have immigrated to the U.S. too, so there’s sense of family around.” For Mukherjee, the journey to becoming an American was a slow process. In the beginning, she was looked upon as very exotic, being one of the few Indian females at the University of Iowa in the heart of the heartland, where there were only some 70 South Asian students, mostly male, mostly studying engineering and medicine. She says, “People would come up and feel my sari in diners outside the university town.” She was supposed to return home after completing the master of fine arts program in Iowa and get married to the Bengali bridegroom that her parents were intending to pick out, but as she recalls, “I was in the middle of three sisters so they first had to find a bridegroom for my older sister and then me. Before they had located one, I had found my own bridegroom, a fellow student, an American of Canadian parentage.”

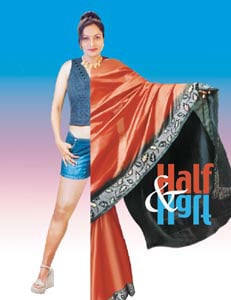

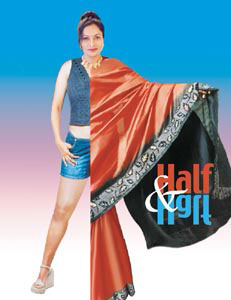

Marriage to novelist Clark Blaise accidentally hurtled her into deciding which country she would live in permanently. The couple spent the first 14 years of their marriage in Montreal where she worked as a professor at McGill University, before moving to the United States with their two sons. Mukherjee, who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley, has echoed the change in her writing too and in August, she has a new novel coming out, titled The Tree Bride. Whereas her first book, Tiger’s Daughter was about an expatriate, her latest Desirable Daughters captures the many options open to immigrants. It was during the writing of the autobiographical book Days and Nights in Calcutta that she became aware of the painful decisions that transformed her from an Indian to an American. “It took me almost 15 years to make that transition from feeling that I’m an expatriate Indian stranded in North America to realizing that I want to be here, in spite of all the problems and challenges that I have to confront.” One rarely saw Indians in that scene and for an Indian to spot another on the streets was to feel a quickening of the heartbeats. But by the 1970’s there was a whole new group of urban Indians, engineers, doctors, and computer scientists, coming in with their families as immigrants rather than foreign students. Slowly the population built up to critical mass. Mukherjee says of the Indian expansion in San Francisco and especially in Silicon Valley, “What America expects of newcomers and what newcomers from South Asia expect of America has very visibly changed. Now you have gradations of desire and expectation on the part of immigrants.” She points out that many people who are doing very well think of themselves as transnational or bi-national, with loyalties to their companies which take them to different countries. All the borders seem to have collapsed. Mukherjee returns twice a year to India to visit family and there her identity becomes so-and-so’s sister, so-and-so’s aunt. She says, “I don’t feel that I’m out of place either in India or here. I think of myself primarily as an American, and if it’s linguistic identity, then as an American of Bengali Indian origin.” Indeed, perceptions can vary from person to person and some may never feel American. The novelist Jhumpa Lahiri was asked by John Glassie of The New York Times why she still found it hard to think of herself as American in spite of having lived virtually all her life in the United States. She replied, “Mainly because my parents didn’t think of themselves as American. You inherit that idea of where you’re from. So calling yourself an American would have been a betrayal. I continue to be hesitant to call myself an American, but I also feel hesitant to call myself anything else.” Glassie’s follow up question on whether she was not comfortable calling herself an Indian either brought this response: ” No, no. My parents told me I was an Indian, but going to India as a child made it apparent that I simply did not have a claim to either country. In the eyes of Indians who never left, I’m not an Indian at all.” And indeed, this is the predicament of many second generation Indian Americans brought up here, and in many cases even their parents are not sure where they themselves fit in for their particular spot in their homeland has disappeared and they too are no longer the same people. “Naturalization and becoming a U.S. citizen is only one part of becoming American; it doesn’t define a person’s identity because people take citizenship or don’t for different, often practical, reasons,” she says. “Becoming American is a much larger, complex, multidimensional process that happens in people’s lives.” She feels a lot of emphasis is given to the behavior and outer mores of people in terms of what is Indian and what is American. Someone dressed in Western clothes would be considered Americanized and somebody in a sari, an Indian; often it’s the same person. She asks, “Does that mean that I have shifted from becoming American one moment to becoming Indian the next?’ It’s not an overnight process, but a gradual change which operates at different levels and many times it takes a whole lifetime when people, only toward the end of the process, realize that they are impacted quite a bit by American life.” For many immigrants, intent on preserving their Indian identity in America, the realization only dawns when they visit India after a long period of absence and see the stark contrast between who they were earlier and the people they have become. They realize that they are not like other Indians, that something has changed in the equation. Can one ever become just a plain American or does one always have a hyphenated identity? “Before one answers that, one has to ask what is a ‘plain’ American identity? It is a complex thing. There is no binary that this is Indian and this is American, though for convenience we may say these things,” says Khandelwal. Many negative stereotypes exist and you often hear Indian parents complain that their children are becoming “too American”. Interestingly, over the years, something called the South Asian-American identity has emerged, especially among the youth. Their parents may still group themselves in social organizations that are identified by nationality, or even sub ethnic groupings, but the new generation is embracing a wider identity. “We will be Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, and Bangladeshis as immigration continues,” says Khandelwal. “But at the same time you’ll find there are areas where these national identities are being transcended and people are coming together.” About a decade ago, the younger generation started to form progressive organizations using the word South Asian as a conscious label, an identity they chose to be known by, to convey the political message that they transcended boundaries of nation and religion. The word Desi is also one that supersedes national boundaries and has caught on with South Asians. “The second generation thinks not just of India or Pakistan, but of their American life also. So South Asian is a very useful, conscious identity that will not replace the national identity,” points out Khandelwal. “There’s a culture that is being shaped that defines who a South Asian is and within that the national identities can be subsumed. I think South Asian is the new ethnic identity that is very much an American ethnic identity that’s forging itself right now.” 9/11 was a defining moment, a nightmarish choreography in blood, smoke and destruction, when many Indian immigrants, mourning the deaths and losses, realized that they were indeed Americans, that they bled when America bled. Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrants lost so many loved ones in the World Trade Center bombings, yet had to endure hate crimes and racial attacks themselves. In this new world, anyone from South Asia was a potential terrorist, and it dawned on these immigrants that the mainstream did not regard them as true Americans. Out of these harsh new realities, the term South Asian gathered even more strength as circumstances framed these identities ever more forcefully. “I do feel I have a leg in both countries and that not just the U.S. has shaped my experience,” says Shah. ” It has definitely made it important for me to make sure that immigrants have a voice in the United States community.” She believes that there are different second-generation experiences, some like hers that are about being transnational. On the other hand, some second generation Indians feel their identity has been molded more in America. “Absolutely. I grew up in this country and various arenas of the South and went to school in the Midwest, so I feel a lot of my being was shaped by my American experiences, including experiences of racism and the understanding that being an immigrant does involve a lot of struggle.” Her experiences have made her realize that it’s important for immigrants to have a voice in America and that the country should be truly representative. At the same time, she says, you cannot erase the fact that immigrants do bring other heritages and cultures into what constitutes America. Khandelwal agrees, pointing out that being South Asian is not in contradiction to being American: “Especially with immigrant life, it’s very clear that they are not two dichotomies, exclusive categories. So there is an ethnic America that we are talking about when we say South Asian. It’s very American.” She adds, “Each group that comes into America transforms itself and establishes over a period of time an ethnic culture that then joins in with other ethnic cultures to create a multi-cultural, multi-racial, multi-ethnic America. Indian life in the U.S. is part of the American multi-ethnic society.” “Pizza may be Italian but you’ll surely find more pizza joints in New York than in any Italian city! There are dishes at the local Chinese take-out that don’t even exist in China. Fortune cookies are an American concoction. The same is beginning to happen with Indian food, as the ubiquitous samosas and curry become a part of American cuisine. Adds Khandelwal, “Food is now representing ethnic life. It’s now become packaged as representing a culture, but it’s very much an American phenomenon.” Whether you live in the suburbs or in the vital enclaves of a Little India, you are a part of America and American life. So even if you think in Hindi, like to dress in salwar kameez and feel conflicted about where you fit in the American landscape, that’s all right because you make your own definition of what it means to be American. While most Indians are comfortable with a hyphenated identity, Mukherjee feels that if we seek it out ourselves it’s fine, but the establishment shouldn’t be imposing hyphenation on us. Why is it, she asks, that when it comes to writers, only Indian American, Chinese American, Japanese Americans or Korean American are hyphenated Americans, but Caucasian writers are simply called Americans. She does feel though that kind of immediately marginalizing – the not quite an American attitude – is dissolving fast. Indeed, America itself is changing, constantly being remade, reinvented by the push of demographics. According to U.S. Census Bureau figures, the Hispanic and Asian-American populations will triple by 2050. The African-American population is set to rise to 61 million from 36 million. The Asian population will jump to 33 million from nearly 11 million today. Non-Hispanic whites will be just 50.1 percent of the population 50 years hence, debunking the stereotype of Americans as white, blonde and blue eyed. The colors of America are changing. Yet the change is not happening evenly and is much more apparent and much more rapid in cities, especially in metropolitan areas and on the two coasts. Many people still live in all-white areas so the change is not visible all across America. Demographics impact politics and Indians are part of a much larger phenomenon of change that’s happening and it will be important to stand up and be counted: “I’m not saying the entire community should have one stand, but we have to decide, are we with some of the other groups, are we aware of this multicultural America that we are part of? It’s a question of taking a position on where we are in all this,” says Khandelwal. As the mighty river of immigration continues to flow, there are people with multiple identities, multiple perceptions, with gradations and nuances of what it means to be American. Newly arrived immigrants are coming into a country very different from the America of 50 years ago. Now they have to give up much less of who they are. The old patterns are changing and today you hear a cacophony of tongues, all part of multi-lingual America. People are holding on to the old and embracing the new simultaneously. Indian Americans are sending their children to classes for Bengali, Tamil and Hindi and India business big guns are establishing chairs for India studies in various universities. Even what it means to be an American or an Indian is very much in flux in this new global world. Identities can be donned as easily as a jacket or a shawl, when air travel, email and cell phones make it possible for an immigrant to take giant leaps across continents. You can chat with your grandmother in a remote village in Punjab even as you sit at a Starbucks in New York. The whispery thin blue aerogrammes have gone the way of the telegram and the telex. Now the click of a mouse connects you to your homeland instantaneously. In this new world you have to give up nothing to become something else. Just as America is becoming a monochromatic world of look-alike Walmarts, Home Depots and McDonalds, so too the entire world is getting a bit more homogenized with CNN and the Internet. In this world of outsourcing and global marketplaces, geographical borders seem to be fading. You can be Indian living in America or American living in India; and sometimes, like the chatty souls at the call centers in India, you can be both and not even stir from your chair! Living in America, surrounded by a virtual U.N. of people of every color and race, it is difficult not to be impacted. They become your friends, neighbors and sometimes, family. The world seems to be opening up and there seem to be many truths, not just one rigid path. “I see American families becoming poly-national families where everyone is going to have a mixture of different language inheritances and so on,” says Mukherjee. “It is beginning to happen in India too, where couples marrying from different regional groups, crossing linguistic barriers, is in itself as big, as bold a step as Indo Americans marrying outside the Indian community.” She adds, “In this age of globalization with young men and women coming from their hometowns to Bangalore, making money, being independent of parental censure is going to lead to a very fast development of a new society in which those old snobberies of linguistic and ethnic origin aren’t so important.” Mukherjee’s son Bart Anand, of Indian and Canadian heritage, married Kim, who is half Irish and half German American and they have just adopted a baby girl from China. Says Mukherjee, “So it’s a very poly-national American family that we represent. What I want to get across is that I hope this will be the way American society goes, that we are all going to be embracing so many different ethnic and racial groups within our families that this whole anxiety about ethnic origin – what does it mean to be a hyphenated American – I hope will disappear.” There are now so many Indian-American families with familial links to other communities, other races. While many Indian immigrants may not view this blurring of ethnic lines positively, it is a fact of life, it is happening. When Mukherjee spoke at a seminar about her family, many people came up to tell her that their families resembled hers.

This month Mukherjee and her husband are headed to Manhattan for the namkaran or the naming ceremony of the newly adopted baby girl. The German American relatives are coming from the Midwest, the Irish American relatives, the Indian relatives are coming from all over – Detroit, Philadelphia, California. “We are all gathering and the child’s name will be – get this – Quinn, which is an Irish name, Xi which is the Chinese name that was on her papers, Anand, because she brings so much joy and it’s my son’s name, Blaise.” So it’s Quinn Xi Anand Blaise. What a perfect American! Says Bharati Mukherjee: “I feel that’s the direction. My hope is that is the direction America will take in defining itself as a wonderful, empowering mixture of many ethnicities, languages and races. |

Half And Half