You people have nothing to celebrate,” Jinder Mahal shouted into a microphone Tuesday night at the Dunkin’ Donuts Center. The current World Wrestling Entertainment champion was dressed in a black turban and a gray suit with his giant belt slung over his shoulder. He twisted his face into a deep, angry grimace, and continued, “But for my people, today marks Independence Day of the greatest nation on earth: the great nation of India!”

Thousands of fans leapt out of their seats, stuck their thumbs down and roared their disapproval. “SmackDown Live” —one of WWE’s weekly live-televised events had just begun, and Jinder Mahal (real name Yuvraj Singh Dhesi) was using an elaborate celebration of his culture to fire up the crowd. The wrestling ring was decorated with a lush rug; a Bhangra dance team made its way down the entrance ramp; a woman in a purple salwar kameez sang the Indian national anthem.

Audience members cheered and took photos as wrestlers made their entrances at a WWE show in Springfield, Mass. Photo: M. Scott Brauer/The New York Times

Dhesi, the first WWE champion of Indian descent, is a heel (wrestling speak for a villain), so it is his job to turn crowds into booing, angry mobs. As part of his persona, he exhorts the crowd with statements of cultural confrontation: that Americans are too clueless to realize that greatness comes from immigrants (and therefore, himself). The heated rhetoric often sounds like it would be at home on a cable news panel rather than a wrestling ring. And on Sunday, it will arrive on one of WWE’s biggest stages: SummerSlam, one of the sports-entertainment company’s core pay-per-view events, where Jinder Mahal will fight a rising star named Shinsuke Nakamura.

WWE performers have long relied on patriotism and “us vs. them” narratives. In the 1980s, a tag team featuring the Iron Sheik and Nikolai Volkoff waved the flags of Iran and the USSR; in the 1990s, Sgt. Slaughter, a onetime patriot, switched his sympathies to Iraq. Recently, Miroslav Barnyashev, a Bulgarian athlete who competes under the name Rusev, wrestled John Cena in a “flag match”; the Stars and Stripes prevailed. But Dhesi has been elevated by the company at very specific moment. One of the pillars of President Donald Trump’s campaign platform was to cut down on unauthorized immigration, and his charged language often linked immigration with crime, spurring protests all over the country. This month, Trump unveiled a proposal to cut legal immigration in half.

|

David Lopez, 32, of Springfield, Mass., holds his son David Lopez, Jr., 7, during a match.Photo: M. Scott Brauer/The New York Times Both Dhesi and WWE executives deny that his storyline was politically motivated or designed to send subtle messages, even as the company has made a large investment in becoming a global product. The WWE is looking to expand into India, a country where sports entertainment is already popular, with a potential audience of 1.3 billion people. Its programming is available now in 180 countries and in 650 million homes, according to a spokesman. It is a publicly traded company and has attracted many big name sponsors, including Snickers and Mattel. “We keep our finger on the pulse of pop culture,” said Paul Levesque, an executive vice president and a longtime performer, known as Triple H. “But we’re more worried about entertainment and pop culture than we are about politics and pop culture.” |

While the matches are merely performances according to executives and athletes alike, the WWE has become entwined with politics. Linda McMahon, a co-founder of the company, was picked by Trump to lead the Small Business Administration. Trump himself took part in WrestleMania in 2007, and in the 1980s, the Trump Plaza in Atlantic City hosted the event twice. He was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013. In July, he tweeted an edited video clip of himself at WrestleMania punching a figure whose head had been replaced with the CNN logo.

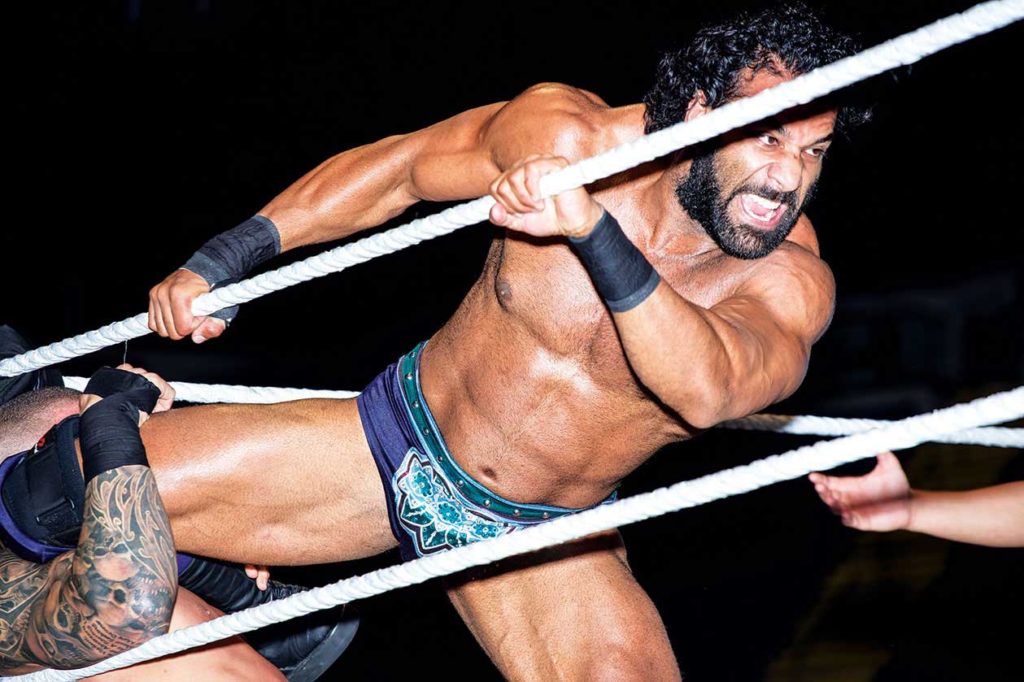

Mr. Mahal and his championship belt. Photo: M. Scott Brauer/The New York Times

The night before “SmackDown Live,” Dhesi was out of character and standing backstage at the MassMutual Center in Springfield, Massachusetts. Shirtless and wearing purple and black spandex tights with a lotus flower on them (a sacred symbol in India), he was using an elastic band to “pump up” — solo exercises to make his many protruding muscles look more muscular. While he was relaxed, friendly and exceedingly polite, he was also intently focused.

“Early on, I would actually tell Vince McMahon, ‘Hey, I’m going to have the keys to the kingdom,’” Dhesi said hours earlier at the Tower Square Hotel, referring to the chairman of the WWE.“‘One day, this place is going to be mine.’”

The journey started in Calgary, Alberta. Dhesi’s parents immigrated to the United States from Punjab, a northern state of India, then settled in Canada. Dhesi, now 31, wasn’t the first in his family to take up wrestling. His uncle, Gama Singh, performed in the 1980s in Calgary’s Stampede Wrestling. Dhesi grew up idolizing the characters of Terry Bollea (Hulk Hogan) and Dwayne Johnson (The Rock). After attending the University of Calgary to study business, he started training, with his parents’ blessing.

Dhesi arrived at the WWE in 2011 and spent three years as mostly enhancement talent or more impolitely: a professional loser. In wrestling parlance, he was a jobber: a performer who exists almost entirely to make other performers look better.

Jinder Mahal, the World Wrestling Entertainment champion, holds his Championship belt as he enters the ring at a WWE Live SummerSlam Heatwave show at the MassMutual Center in Springfield, Mass. Photo: M. Scott Brauer/The New York Times

“I just had lost focus,” Dhesi said. “I had kind of become complacent, which is the kiss of death in the WWE.”

He was released in 2014, and started dabbling in real estate. He considered buying a Subway franchise, but decided to rededicate himself to wrestling.

“There’s people that were entering the WWE from football or other sports that are my age so I realized that if I regained my focus, regained my drive, there’s no reason I can’t come back to the WWE,” Dhesi said.

The first step was getting into shape. He stopped drinking alcohol, which he blamed for limiting his drive, eliminated junk food, and embraced an extreme training regimen. In summer 2016, he got an unexpected call from the WWE. Would he like to come back?

When he returned, Jinder Mahal was still a jobber — losing often — but in April, his story saw a creative shift: He became a winner. At the time, Dhesi’s gimmick was about practicing peace. But McMahon made a change: He wanted Jinder Mahal to talk about his immigrant roots and an America in decline. Dhesi, who first visited India when he was 10, was uncomfortable at first but dutifully carried out his boss’s wishes. At the Wells Fargo Arena in Des Moines he addressed then-champion Randy Orton.

“Randy, you’re just like all of these people!” Dhesi said, shooting his opponent a piercing glare. “You disrespect me because I look different! You disrespect me because of your arrogance and your lack of tolerance!”

He was wearing a turban. And then he spoke Punjabi. The crowd expressed its disapproval.

“The reaction was great; I heard the crowd that day,” Dhesi said. “I was elevated to star status just within that one promo.” With more eyes on his giant, rippled physique came speculation that he is using steroids (Dhesi has passed all of his drug tests mandated by the WWE).

Dhesi won the championship at a pay-per-view in May called “Backlash” just weeks later. While it was hard not to notice that his character was leaning into heated immigration rhetoric, “We really are no different than a great book, a great play, a great movie, an opera and even more applicably, a ballet,” said Stephanie McMahon, chief brand officer of the WWE, as well as an occasional performer. “We tell stories of protagonists versus antagonists with conflict resolution. The only difference is that our conflicts are resolved inside a 20-by-20-foot ring.”

However, the WWE has historically struggled with its depictions of minorities, where villains like the Jinder Mahal character have existed for decades.

In one of the most extreme examples from 2005, a character named Muhammad Hassan — played by an Italian-American named Marc Copani — prayed on the entrance ramp as masked men beat on one of the most popular WWE wrestlers of all time, the Undertaker.

The show aired the same day as a suicide bombing in London. It caused immediate outrage, and the Muhammad Hassan character vanished.

Since then, the WWE has shifted toward a more family-friendly approach and is making an effort to include more South Asian performers.

It recently signed its first female wrestler from India, Kavita Dalal. Jinder Mahal has two henchmen of Indian descent, the Singh Brothers (real names Gurvinder and Harvinder Sihra), who are real life brothers and once made up a tag team known as the Bollywood Boyz.

Dhesi said he is willing to push back on writers if he deems something racially insensitive, although he added that hasn’t happened yet.

In Providence, Mohan Srinivasan, who immigrated to the United States from India in 1987, came to “SmackDown” with his 20-year-old son, Siddarth Mohan, a senior at the University of Connecticut. As lifelong wrestling fans, both have watched Dhesi’s rise with pride.

“India is getting exposure in this company that it never got before,”Mohan said.

| In the backdrop of Jinder Mahal’s rise is the WWE’s push into India, where Dhesi’s star is quickly rising. According to Michelle Wilson, the company’s chief revenue and marketing officer, the WWE hopes to return to the country for at least one event this year. She also said about 60 million viewers from India watch WWE programming every week. The company launched a new weekly television show, “WWE Sunday Dhamaal,” that rounds up the best action in Hindi. In April, the company held an audition in Dubai, where more than a quarter of those trying out were from India.

But skeptics note that the company has a long way to go. Mr. Mahal enters the arena with his allies, the tag-team duo known as “It’s one of those things that sound good to stockholders,” said David Bixenspan, a wrestling writer for Deadspin, referring to expansion into countries with large populations. “They haven’t really been able to make a dent yet.” And Dhesi isn’t the WWE’s first high-profile Indian performer. A few years ago, Dalip Singh Rana, an Indian-born wrestler known as the Great Khali, briefly held the World Heavyweight Championship. But Dhesi’s character is different. The Great Khali never spoke about being an immigrant. In fact, he rarely spoke at all. Jinder Mahal calls himself “the modern-day Maharaja,” and yes, you can buy T-shirts that say that. When Dhesi took part in segments that involved Bhangra dancing, for example, he insisted on their being genuine to the culture. “I knew that this was an opportunity to get major media attention in India but only if it is done correctly and done authentically,” Dhesi said. And whether he means to or not, Dhesi’s character is evoking a fraught immigration dynamic in the United States. “I’m actually really glad they put the title on him,” said Robert Everson, 27, after the Springfield event. He said he had been attending wrestling events since he was 5. “Jinder Mahal really is a wake-up call. Not only to the fans but to America as well, because when he speaks about how Americans are reacting to the world, it’s truth.” |

© 2017 New York Times News Service