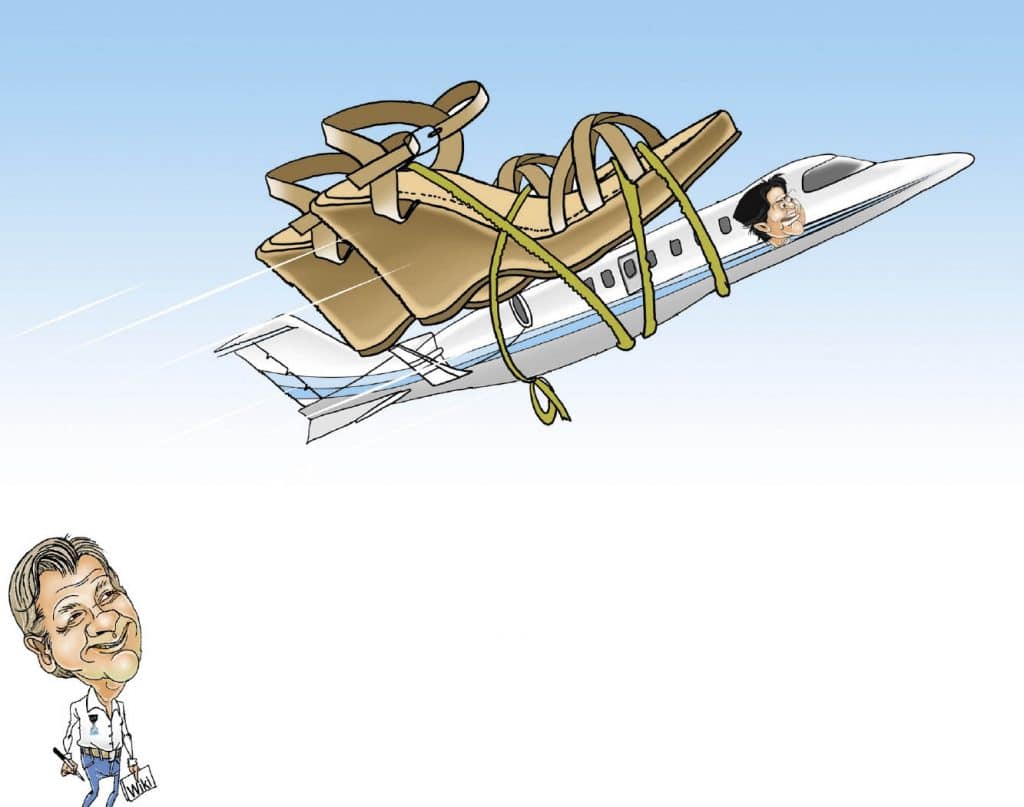

The Indian media was in a tizzy last month over reports that Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Mayawati flew her private jet “empty to Mumbai to retrieve her preferred brand” of sandals.

The sensational claim was derived from a colorful 2008 cable, titled ÒPortrait of a Lady,” sent by the political consul at the U.S. Embassy in Delhi, which ridiculed Mayawati as Òa virtual paranoid dictator replete with food tasters and a security entourage to rival a head of state.”

The cable, disclosed by Wikileaks as part of its trove of almost 250,000 secret U.S. cables worldwide, recounted another colorful rumor “in which a State Minister was forced to do sit-ups in front of her as penance for not first asking permission to call on U.P.’s governor.”

The cable’s other startling claims – that Mayawati “employs nine cooks (two to cook, the others to watch over them) and two food tasters’ and that “in addition to this outsized security apparatus, she constructed a private road from her residence to her office, which is cleaned immediately after her multiple vehicle convoy reaches its destination” – were widely reported, as were its assertions that “Mayawati is obsessed with becoming Prime Minister,” and that journalists in the state are fearful “the government has tapped their phones as well as those of civil servants.”

A livid Mayawati, in her characteristically bombastic style, escalated the controversy a notch by blasting Wikileaks’ Julian Assange, as having “gone mad” and “we can make room for him in the Agra mental asylum.” Assange returned fire, inviting Mayawati to Òsend her private jet to England to collect me, where I have been detained against my will …. I would be happy to accept asylum, political asylum, in India – a nation I love. In return, I will bring Mayawati a range of the finest British footwear.”

The India media had a field day with the tit-for-tat between Assange and Maywati, before moving on to the next entertaining drama.

Lost in the week-long hoopla in the Indian media was whether these outrageous allegations were actually true. The classified U.S. cable relied upon a single unnamed Lucknow journalist for some of the most sensational claims, which were not investigated, much less substantiated, by the embassy before being incorporated into the report. The rumors, presumably peddled to gullible U.S. embassy officials by an imaginative journalist, who could not publish them in his own publication likely because they did not meet even the minimal journalistic standards of local tabloid media, were regurgitated as gospel by India’s mainstream press once they were unloaded by Wikileaks.

Perhaps the most startling aspect of the U.S. cables disclosed by Wikileaks is the volume of unsubstantiated rumor and gossip that is peddled in these reports that inform U.S. foreign policy globally. The allegations against Mayawati may well be true and they certainly are not outside the realm of the popular narrative about her outsized ego.

She is reportedly India’s richest chief minister with personal wealth exceeding $20 million, according to her own financial statements, and has built grandiose monuments to herself all over the state. But the Wikileak cables gave license to supposedly respectable Indian media outlets to publish salacious, unverified gossip as fact, without even a cursory examination to determine their veracity. To this day, not a single Indian media organization has undertaken an independent investigation to explore not just the allegations against Mayawati, but some of the other equally dubious claims in the thousands of Wikileaks cables relating to India, many of which have received widespread exposure in the media.

The U.S. cables are a frontal window to the ineptness and dysfunction of the U.S. foreign policy apparatus. If clueless diplomats can peddle unsubstantiated rumor and gossip drawn from a journalist’s bluster over coffee, is it any wonder that the U.S. government was led astray in its assessment of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, resulting in a colossal $800 billion mistake in the form of the cost of the war in Iraq.

Bombing Bollywood

In this make-believe world of U.S. diplomacy, it is scarcely surprising that its diplomats would let their imagination run riot. Pressed to throw up recommendations for help in Afghanistan’s reconstruction, U.S. embassy officials in India lifted a discredited page out of the Cold War and World War II, when the U.S. government marshaled Hollywood studios for the wars, with a proposal to channel Bollywood’s appeal in Afghanistan for its propaganda efforts in the country. A March 2007 cable from the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, noting that “Bollywood movies are wildly popular in Afghanistan,” proposed that Òwilling Indian celebrities could be asked to travel to Afghanistan to help bring attention to social issues there.”

The cable outlined several “specific, concrete ideas for opportunities for India to use soft power in helping Afghanistan’s reconstruction, with the broader objective of seeking ways for the U.S. to synergize its efforts with Afghanistan’s ‘natural ally.'”

It is unclear whether the U.S. ever acted on the proposal, deterred perhaps in part because, as the cable outlines, “Security continues to be an issue of public concern in sending Indians to work in Afghanistan.”

As the Economic Times wrote in a mocking editorial, “Winning Ways: Bollywood in the Afghan Wars’: “With Bollywood’s reigning deity Shah Rukh Khan actually tracing his ancestry back to the same stark land (Afghanistan), it is entirely logical that the Americans would have wanted to rope in the big guns of the Bollywood brigade to capture key theatres in Afghanistan… A few star-studded, bump-and-grind Bollywood extravaganzas could well have been far more effective in luring out those lurking in the deepest recesses of the Tora Bora mountains than drone attacks.”

Empty Suits

The cables are often contradictory, even on issues of profound import for U.S. policy. For instance, US envoy David Mulford dismissed Congress General Secretary Rahul Gandhi as an “empty suit” in 2007, less than two years before the embassy was raving about his mastery as a politician and potential prime minister.

In a cable dated Oct 23, 2007, Mulford wrote: “Little is known about Rahul Gandhi’s personal political beliefs, if any. He is reticent in public, has shunned the spotlight, and has yet to make any significant intervention in Parliament. His singular foray to center stage during the UP elections was unremarkableÉ. He is widely viewed as an empty suit and will have to prove wrong those who dismiss him as a lightweight.”

Just 20 months later, on May 27, 2009, however, the US Embassy was singing an entirely different tune, praising Gandhi as a “practiced politician” who was Òcomfortable with the nuts and bolts of party organization and vote counting” and a Òcredible candidate for prime minister.”

Indeed, Peter Burleigh, the U.S. charges d’affaires, wrote: ÒHe was precise and articulate and demonstrated a mastery that belied the image some have of Gandhi as a dilettante.” He might have ascribed the mistaken image to the U.S. ambassador as well, who, after all, had expressed precisely that view. That may well have been imprudent for a charges d’affaires, but then the embassy cables are notable for their undiplomatic, occasionally even tactless, journalistic-style narrative, replete with titillating headlines and subheads, such as the ones on Rahul Gandhi: “The Son Also Rises,” “Here Comes the Son,” “Rites of Passage,” “Grooming the Heir,” “Changing of the Guard,” “Youth Quake,” “Young Man in a Hurry,” etc.

Duplicity

Perhaps the most revealing and underreported aspects of the disclosure of the embassy cables are the politicians, policy makers and businessmen who shared their duplicitous, occasionally even illegal, conduct with U.S. officials – assuming that the cables represent them accurately.

Considering that journalists have been known to fabricate stories and sources in their highly publicized reports, it is not outside the realm that some of the representations in the classified cables are faked, which is cause for even greater alarm for U.S. foreign policy.

But if the cables are accurate, the duplicitous and cynical conduct of Indian politicians and government officials they capture is breathtaking. For instance, according to a Dec. 17, 2009, cable, the Indian government was merely posturing, but not really keen on the extradition of David Headley, the main accused in the Mumbai blast, from Chicago.

U.S. ambassador Timothy J Roemer said in the cable that National Security Advisor MK Narayanan had told him that it was “difficult not to be seen making the effort,” but that the government was not really keen on Headley’s extradition “at this time.”

According to another cable five days ahead of a crucial vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha over the Indo U.S. nuclear deal, Congress leader Satish Sharma’s aide Nachiketa Kapur showed a U.S. embassy employee two chests containing cash, reportedly part of Rs 50 to 60 crore fund the Congress had assembled to bribe parliamentarians to support the nuclear deal. Kapur, according to the cables, told the embassy official that four MPs belonging to Ajit Singh’s Rashtriya Lok Dal had been paid Rs 10 crore each to support the government.

The Manmohan Singh government won the vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha with 275 MPs voting in favor of the UPA and 256 against it, perhaps in part by subverting democracy by bribing MPs, with the full knowledge and at least grudging approval of the U.S. government.

A review of atleast the Indian cables in the Wikileaks trove of leaked diplomatic cables makes it clear that embarassment, more than national security, may be what the U.S. government is so desparate to conceal.