Clad in a light blue checkered shirt and denim pants, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, one of India’s most decorated and celebrated musicians, is perched on a bench under a tree outside a coffee shop at Stanford University, indistinguishable from scores of graduate students and faculty milling about on this crisp Spring morning. He is at the university teaching a course at the Braun Music Center and his presence, as he speaks to Little India, reflects what the Dalai Lama once said, his performances do, “When Amjad Ali Khan performs, he carries with him a deep human spirit, a warm feeling and a sense of caring.”

Anna Schultz, an ethnomusicologist and assistant professor at Stanford, raves: “The experience of having Ustadji teach at Stanford was amazing. Today was the last class, and none of the students seemed to want to leave the classroom when the time was up. They became very attached to Ustadji over the course of the quarter, and even those with no prior experience in Indian music have become addicted listeners to Indian classical music.”

Schultz invited Khan to teach at Stanford. She says: “I can tell that the students appreciated the special attention that Ustadji gave to each and every one of them, and they blossomed under his patient guidance. During the class recital in June, they exuded happiness and confidence as they sang the difficult compositions that he taught them.”

Suddhasheel Sen, a student, concurs: “Ustadji has taught me how to think about music, I have realized for the first time in life how the taal (pre-set rhythm beats) meets the sum (first main beat of the composition). It liberates my brain, there is no theory needed. I have experienced sound, realized rhythm; it has been precious!”

What has been your experience teaching at Stanford University?

In one word: wonderful! This is the first time that I have actually stayed in the Bay Area. I have performed in San Francisco several times, but never really enjoyed or experienced the multicultural diversity of the San Francisco Bay Area.

How do you teach Indian classical music to a westerner?

Let me tell you through examples and experiences I have had teaching here. I have had a wonderful teaching experience at Stanford. From the first class onwards, it has been undoubtedly great. I have opera singers, violinists, flautists, singers, and guitarists in my class.

This is absolutely okay, because I am here to teach music, which, I believe, has no boundaries. I teach them note clusters and tell them to just feel the music and perform. My goal is to have them experience a different world of music through what I teach. Notes are the same in Indian and western music — Sa re ga ma pa dha ni is Do re mi fa so la ti. Why do you think music unites everyone? It is because music transcends the two most dividing aspects — religion and language.

I teach these students compositions that have no words, called taranas. I tell them to follow the rhythm and sound. I tell them to forget about the theory and just follow me. I want to teach my students here how to feel music and with that they will also start understanding the basics as well as the intricacies.

Do you see any difference in audiences’ worldwide, for instance when you compare audiences in India versus those in European and North American cities?

My experience with U.S. audiences has been very memorable. People are just much more involved and truly appreciate an artist. Many years back, on the occasion of India completing 50 years of independence, I had performed at Carnegie Hall. Stalwarts like sitar maestro Ravi Shankar were in the audience. As soon as I entered the stage, I received a standing ovation. I hadn’t even started performing.

This izzat (respect) that western audiences show is so humbling that I find myself giving my best. In 1984, I performed in Boston at the Michael Dukakis Hall and the after the concert they declared April 20 as Amjad Ali Khan day.

In India too, at some places audiences are very appreciative, but overall I feel like we need to have Indian audiences learn artist appreciation from western audiences.

I’ve heard several of your live concerts and recordings. One thing that is common in all of those is your ability to captivate listeners in the first few minutes. What is this intangible “something” that very few musicians possess?

Thank you for your kind words. It is the dua (blessings) of my elders and guru. I think what you feel is the utmost sadhana (meditation) that I do through my music. For me music is everything. I breathe it; I think about it, I am because I have my music and family. When I play a certain raga, I try to present the complete picture through it. Like a painter, I try to draw strokes as well as mix various textures, moods, and colors. I also like to present traditional compositions in their entirety. These days I see several musicians playing only a line of a particular composition and not even completing it. This, in my view, is not right. The ancient compositions that we have in Indian classical music are priceless. In those few notes the whole deep soul of a raga is captured and it is our duty to present them and have the world hear what rich music we have.

You said you are because of your music and your family. Can you elucidate?

I exist only because of and for these two. I am married to the most wonderful woman, my wife Subhalakshmi, for the last 37 years. We have two sons, Amaan and Ayaan, and with God’s grace they both play beautiful music. Infact, my elder son Amaan is here with me at Stanford and also performed a Jugalbandi with me last week.

Talking about my closeness to my family, let me tell you an incident that happened in 1984. I was on a concert tour in the U.S. and in Los Angeles, Michael Jackson heard me play. He really liked my music and sent me an invitation to visit him at his home. I had been away from my family for almost two months and was missing them immensely. I couldn’t bring myself to go to that party and sent him a message to kindly excuse me as I really needed to be with my family.

Do you believe in words like fusion and conventional music?

I think conventional is an unhealthy word. I like the word tradition better. When you say tradition it allows for innovation and improvisation. As far as fusion goes, I feel that it is a wonderful thing to collaborate with other forms of music to present a unified picture. As I always say, music shouldn’t have any boundaries. When you abandon all boundaries and perform with your soul, it is going to reach every person.

Infact, I have experimented with modifications to my instrument throughout my career. I played with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and worked as a visiting professor at the University of New Mexico. In 2011, I performed on Carrie Newcomer’s album Everything is Everywhere with my sons.

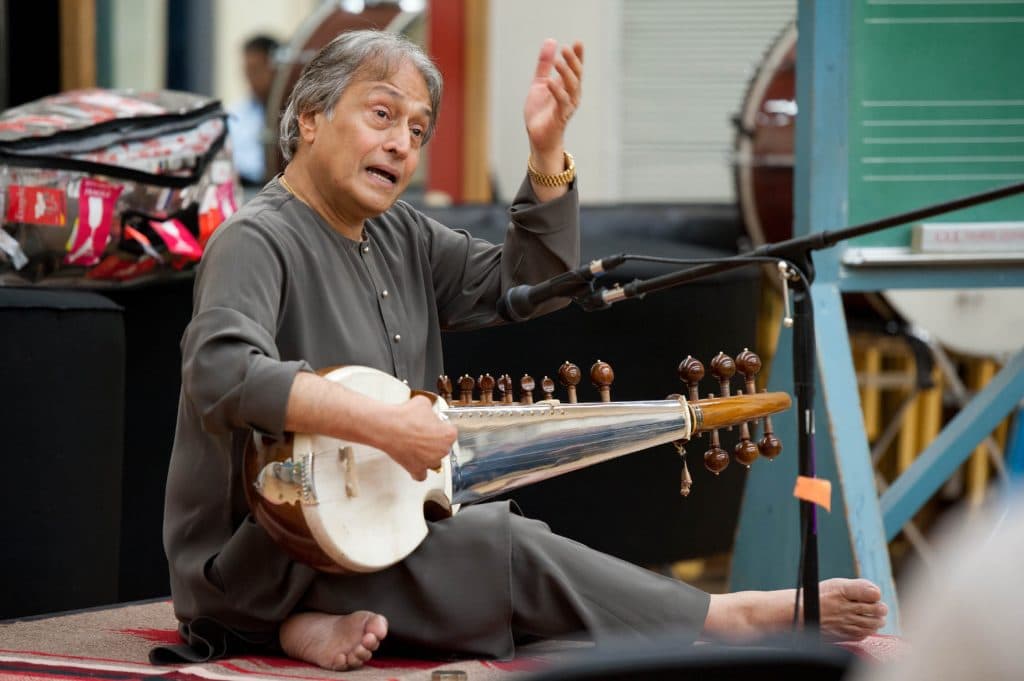

Very recently my concerto for sarod and orchestra, Samaagam, the result of an extraordinary collaboration with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, is the latest embodiment of how I have given a new form to the purity and discipline of the Indian classical music tradition. Samaagam was released worldwide in April 2011.

You have achieved so much in your life, what is next for the Ustad?

Continue my sadhana (meditation) of music and share as much as possible with those who want to learn. This is all I want to do for the rest of my life.

Khan’s wife, Subhalakshmi, appears with a steaming cup of chai and a bottle of juice. Smiling and handing me the juice she says, “Now drink this as for the last one hour I know you have been busy talking.” Khan gazes at her admiringly.

As I prepare to leave, Khan graciously stands up and offers to walk me to the car and invites me to his home in New Delhi as well as his ancestral home, which has been converted into an instrument museum.

As his students gather around him asking questions and humming the compositions he has taught them over the past eight weeks, you can see his eyes twinkling with joy and satisfaction. It is clear that the single most important force driving this incredible musician is the power of sharing his vast knowledge with those so eager to seek it from him.