Sunayana Dumala tried once again to enter the worship room she and her husband, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, had created in their home for daily prayers. Kuchibhotla had built an intricate wooden shrine by hand two years ago, a small sacred edifice where they would kneel each morning. Months after his death, it became a place where she would honor him.

On a Wednesday night in February, a man with a semi-automatic pistol and a distorted notion of American pride turned ordinary people into shooting victims and survivors — and he turned Dumala into a widow.

Kuchibhotla, an Indian-born engineer, was confronted about his immigration status at a bar, then fatally shot. By the time police arrived, Kuchibhotla was dying, and his close friend Alok Madasani was wounded. Another patron who tried to stop the attack was also struck by gunfire.

Three months to the day after her husband’s murder, Dumala stood at the entrance of the prayer room alone, looking toward a window that framed storm clouds. She turned away.

“Everything about this room, everything about this house,” she said later, “reminds me of my Srinu,” the nickname she gave him during their courtship.

It was in the quiet of the next morning that Dumala, 32, decided that would be the day she would step inside the worship room. What had been unbearable just the previous day seemed surmountable, if only because it was the next painful step.

So she willed herself up the stairs, inching past the framed collage of wedding photos, and into the room. She cleaned each of the deity figurines with warm water. Then she prayed for peace in a whisper just above the sound of children’s play at the elementary school next door.

‘Do We Belong Here?’

In some ways, what one man shouted in anger and one woman uttered in grief capture one of America’s most troubling intersections.

“Get out of my country!” the gunman would yell, before opening fire on the two Indian men he later said he believed were from Iran.

“Do we belong here?” the widow would ask in a Facebook post six days after the shooting

The episode happened at dinnertime in a neighborhood bar, part of a spasm of hatred that seems to be uncoiling in small towns and big cities across the nation — and in rising numbers.

A month before the shooting, the Victoria Islamic Center in Texas was torched, destroying the mosque. A month after the shooting, a white supremacist traveled from Baltimore to New York City on a mission to randomly kill a black man. He did just that. The reason: a deep hatred of black men, according to the New York Police Department.

“We’ve read many times in newspapers of some kind of shooting happening,” Dumala said at a news conference in February at the headquarters of Garmin, where Kuchibhotla worked as a senior aviation systems engineer.

And we always wondered, how safe?”

Dumala had wondered how the couple fit into this new narrative, if they should move to a different country, and once even asked her husband, “Are we doing the right thing of staying in the United States of America?”

Dumala shared what is now the most dreadful chapter of her life seated at the foot of the king-size bed where they once slept. Much of their story was typical, abundant with promise: They were Indian immigrants who moved to the United States from Hyderabad for postgraduate degrees and jobs, a young couple in love, planning a family, making Kansas home.

Her night stand, closest to the window, offered unintended markers on that life: a 2007 college graduation photo of Kuchibhotla taken not long after they met, and a small box of Russell Stover assorted chocolates he gave her for Valentine’s Day, eight days before he was shot.

The realization that her husband was killed because of intolerance, because he was not born in America, is what forced her to emerge from this personal, private hell.

She thought that if people were to know the aftermath of a hate crime, the crater-sized void and endless questions left behind, if the victims were rendered as three-dimensional, maybe there would be less fear, less hate.

“My story needs to be spread,” she said plainly. “Srinu’s story needs to be known. We have to do something to reduce the hate crimes. Even if we can save one other person, I think that would give peace to Srinu and give me the satisfaction that his sacrifice did not go in vain.”

A Prescient Dread

On the morning of his death, Kuchibhotla left for work before his wife. “Bye,” he said, hurrying past her, a casual farewell that would come to haunt Dumala for its brevity and finality.

Just before 6 p.m., Dumala texted and called Kuchibhotla to plan for the evening. His cellphone was off, which was not unusual, because of his habit of watching videos, draining the battery.

She had hoped they could spend time that evening in their backyard, sipping tea and watching the sun lower into the horizon. The view, a wide-open stretch with houses dotted in the distance, was one of the charms of their deep blue two-story house in Olathe, an orderly Kansas City suburb in Johnson County, Kansas.

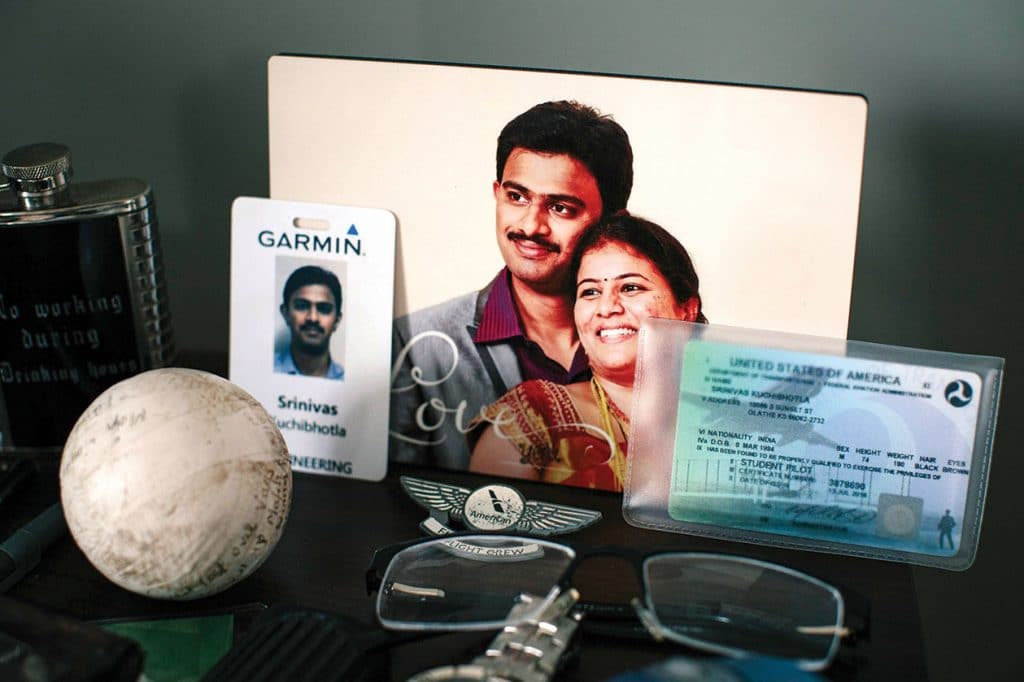

On a night stand, IDs, personal items and a photograph of the couple.

Dumala picked at her roti in between calls to their friends looking for her husband. Maybe he had gone to have drinks at Austins Bar & Grill, his favorite after-work spot, with Madasani, one of his best friends from work. But Madasani’s phone was off, too.

She began to scroll through Facebook. A news story popped into her feed: three people shot at Austins.

“I was getting scared, some kind of feeling was going through me. I was all alone,” she said, pausing to catch her breath, her face dampened by tears. “This is not my usual Srinu, I am saying to myself. He would have reached out to me somehow to let me know he is safe.”

Dumala’s instincts were right. The best friends, more like brothers, were at Austins. Typically the two went with another close friend from the office, Manju Nag, but he had been out of town on business. That night, it was just Kuchibhotla and Madasani at their regular table on the patio, the one closest to the door, discussing Bollywood movies and drinking a pair of Miller Lites.

The assailant approached the friends. Witnesses recall him wearing a white T-shirt with military-style pins, his head wrapped in a white scarf. He was intent on finding out one thing: Did the men at the table belong in the country?

Adam W. Purinton, a white Navy veteran, turned to the two brown-complexioned men, both living in the United States for years, and demanded to know their immigration status.

“Out of the blue comes this weird-looking gentleman, I say weird-looking because he had anger on his face,” said Madasani, 32, an aviation systems engineer at Garmin. “I did not hear what he was saying instantly, but I saw the look on Srinivas’ face change drastically. I looked at Adam and he walked towards me, he came to me and said, ‘Are you here legally?’”

Peppered with more questions and ethnic slurs, Madasani did not respond. Instead, he went inside to get the manager. Ian Grillot, 24, and another patron asked Purinton to leave and escorted him from the patio. As Madasani returned to the patio area, he said he heard more of the rant. “Oh, here comes the Arab,” Purinton said.

But he didn’t go far, pacing outside in the parking lot. Madasani said he and Kuchibhotla had decided to leave, but were stopped as other patrons apologized and assured them they were welcome. One guy paid their tab; the bar manager gave them another round of beer and fried pickles, a favorite of Kuchibhotla. “Everybody kept coming up to us saying this is not what we represent, you guys belong here,” he said.

Not long after, according to the authorities, Purinton returned to the bar with a handgun. He stood in the patio door, pointed his gun toward the two men, and fired.

Proposing to Him, Online

They had met online in 2006 after a mutual friend gave her a list of names of Indian students attending the University of Texas at El Paso. She was considering a master’s program there and wanted to get a feel for what to expect as an immigrant student. She sent a note to the first name on the list: Kuchibhotla.

They were both from Hyderabad, the riverside capital of Telangana state in southern India. He grew up the middle of three sons and loved cricket as a boy, playing on the rooftop of his family home. His father was a quality assurance officer for a pharmaceutical company and his mother was a teacher.

“He was the tallest of all of us brothers and cousins,” said Sai Kota, a cousin who grew up with Kuchibhotla and now lives in Edison, New Jersey. “We used to volunteer him to get the ball when it would go onto another rooftop. He could jump to the other rooftop. He was a brother and mentor to me.”

Dumala was immediately drawn to Kuchibhotla’s sharp focus, sense of humor and patience — she still likes to tell the story of the many weekends he took her to empty parking lots to teach her to drive. He liked the sound of her voice, melodic and sweet, and her caring nature — almost every day, she checked to make sure he had eaten breakfast.

Their casual phone conversations blossomed into the beginnings of a six-year courtship. After three months, Dumala proposed to him one night. No matter that she had never seen him in person.

They finally met months later at a temple when he went home to Hyderabad. “I did not know that he was going to be 6’2”, with me being 5 feet,” she said, chuckling.

She ended up attending St. Cloud State University in Minnesota, where she studied engineering management and graduated in 2010. After Kuchibhotla’s graduation in 2007, he accepted a job at Rockwell Collins, an avionics and information technology company in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where he worked as a systems engineer in the flight control department.

He loved everything about aviation, particularly the very idea that something so heavy could fly.

At Rockwell, he met Madasani, who would become one of his best friends and a roommate. Madasani moved to Kansas in 2014, joining his friend Kuchibhotla at Garmin.

Kuchibhotla persuaded his parents and his wife’s to bless their marriage, built upon love, rather than arranged. The couple married in 2012, in a ceremony in Hyderabad attended by more than 1,000 people.

In 2014, they moved to the Kansas City area, mostly to find opportunities for Dumala. She had stayed home much of their time in Iowa, unable to work with an H-4, for spouses of specialty workers who hold H-1B visas.

They found a home in Olathe, population 135,000, a city 20 minutes outside Kansas City and one of the fastest-growing in the nation.

Kuchibhotla continued his work as an engineer at Garmin. He helped companies that build airplanes and helicopters integrate Garmin technology and software into their aircraft. He was so well regarded that his boss routinely asked if the human resources division could “find more Srinivases.”

“This is not hyperbolic when I tell you he was almost the perfect employee,” said Dave Wysong, his supervisor. “He was a great engineer. Technically, very, very good. He was quiet and very, very friendly.”

Dumala started work as a database developer at a pharmaceutical marketing agency in May 2016. The couple became part of a circle of Indian friends who spent most every weekend together at dinner parties. The men played on a cricket team, where Kuchibhotla was the bowler, the pitcher’s position. Two years ago, they moved into a subdivision near Garmin. And last year, they began planning a family.

The End of the Day

It was 7:15 p.m. The work day had ended, and most people were home, headed there or winding down.

On this particular Wednesday, the winter sun had already set, but it was unseasonably warm, in the high 70s. It was just after halftime of the University of Kansas basketball game against Texas Christian University. Kansas was up a point and a win meant the team would clinch the Big 12 conference title for the 13th year in a row, which also meant Austins was packed with Jayhawks fans besides its usual cast of regulars, among them Kuchibhotla, Madasani and Grillot.

Dumala was at her Olathe home, 3 miles away, eating dinner and scrolling through Facebook.

Kuchibhotla and Madasani were back at their table talking. The crowd on the patio had thinned out during the halftime break, but the televisions were still blaring.

Suddenly, the sound of gunfire. “Pop, pause, then pop, pop, pop,” said Tim Hibbard, the owner of a software company who was sitting at the bar sipping a Blue Moon beer. “It wasn’t like the movies where the gunfire is large and demanding of attention. The sound was subdued, almost underwhelming. Low fidelity is how I would describe it.”

Kuchibhotla was hit first. Madasani, who had been sitting on the other side of the table, hit the ground, forced by a bullet, instinct or both. He crawled on his belly toward the opposite door. He thought the bullets were close by because the floor shook with each gunshot. “All I was thinking about at the time was about my baby, all I was thinking of was my wife’s belly,” said Madasani, whose wife was pregnant with their first child, a boy due in July. “In flashes, I was thinking, ‘I have to live.’”

Once outside, he realized he was shot in the left leg. “I saw Srinivas on the floor, not moving. I kept on yelling to everyone, ‘Leave me, go and attend to him.’”

Grillot, the bar patron who had intervened earlier, chased Purinton into the parking lot. Purinton turned and shot him in the chest and hand.

As people scattered, Vincent Baird, who was headed to the gas station across the street, ran toward the chaos to help. With four years of experience as an Army medic, he went straight to Kuchibhotla, whose breathing was shallow and labored.

Once on his knees, Baird could see a gunshot wound in his chest. With the help of two others, Baird said, he cut a 4-inch square from an unused garbage bag and taped it over the wound. He then checked for other wounds and, seeing none, he turned him on his side.

Kuchibhotla stopped breathing at a couple of points, Baird said. Each time, he performed chest compressions until Kuchibhotla started breathing again and an ambulance arrived. He was pronounced dead at the University of Kansas Hospital.

Purinton had fled amid the chaos. He ended up 80 miles away at a bar in Clinton, Missouri, where he told a bartender that he had shot “two Iranians.”

The Officers at the Door

Hours after the shooting, Dumala was an emotional wreck. Finally, she found the courage to search for more details on the shooting at Austins. The reports had not identified the victims, but included the name of the hospital in downtown Kansas City where they had been taken. What she didn’t know was that her husband of four years was already dead.

A car pulled into the driveway. It was one of their friends, Shashi Bolaram.

Dumala opened the door. Voice quivering, she asked him, “He was there, wasn’t he?”

Bolaram nodded.

Before Dumala could fully process what that might mean, there was a second knock at the door. She sat on the second stair as two Olathe police officers confirmed Kuchibhotla’s death.

On the half-hour ride to the hospital, Dumala sat in the back seat of a friend’s car, her mind cluttered and spinning. It came to rest on this incomprehensible notion of sudden loss: Her beloved Srinu was dead. She remembers hearing her own hollowed voice pose an endless loop of questions to herself, each more desperate than the last: “What should I do? What is this life? Is it true that I cannot see Srinu? Is it true that I can’t hear his voice? Is it true I lost the person who loves me the most?”

The next day, Dumala learned the horrific details of her husband’s murder. An Olathe police officer and an FBI agent told her who had killed him and why.

The police officer — who was stopped by Dumala from uttering Purinton’s name — also said that it appeared the shooting was premeditated.

“Hold on,” she said, stunned. “What do you mean?”

“Something planned,” he said.

“When? At that moment? In that night?” she pressed, the questions crashing into one another.

The reality of what had happened to her husband began to wash over her.

“At least until then, I was of the opinion that this was some random guy who came in and just shot three people, and my husband was unfortunate to be there,” she said. “That was a lot harder for me to hear.”

Purinton, 52, was formally charged with premeditated first-degree murder and two counts of premeditated attempted murder. Last month, he was also indicted on federal hate-crime charges.

The term “hate crime” was being used over and over by police, journalists and politicians to describe the death of her husband. All of a sudden, Kuchibhotla was a hate crime statistic, an example to bolster anti-hate legislation and now linked, fairly or not, to President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. Days after Kuchibhotla’s death, the president issued a statement condemning the shooting.

Dumala was aghast, baffled by the man who took her husband from her. “That guy, I think he was hurt, I don’t know what hurt him,” she said. “What is he doing by taking away this life? Did he serve his purpose? Did he lessen his anger? Even I have anger now, but that does not give me the right to go and take away his life.”

The funeral home made arrangements for Kuchibhotla to spend a final night in his Olathe home — a first for the company. His body was transported to the house in a discreet white van.

“We did everything to accommodate their requests. We also wanted to be culturally sensitive and show the family that our community was behind them,” said Christopher Holland, the funeral director. “We wanted them to heal from this tragedy.”

Kuchibhotla was in repose on a cot in an empty dining room that he had painted an elegant burgundy where family and friends paid their final respects. He remained with Dumala and her family until early that Saturday, when he was returned to the funeral home to be prepared for the trip to his homeland.

On a Tuesday afternoon in Hyderabad, the body of Srinivas Kuchibhotla was placed on a pyre of logs. His funeral was held nine days before what would have been his 33rd birthday.

Return to an Empty Home

Dumala returned to Kansas with her parents in April, staying with a friend until she could summon the strength to return to her home without Srinu. She spent her first few weeks back in Kansas trying to figure out the next chapter, difficult to define because her visa status is now in limbo. She is also looking for the best way to help reduce hate crimes.

Before her husband’s death, Dumala shopped at KC India Mart in Overland Park, where she could find foods imported from home. Over the years, she and her husband had become friendly with the owners, and when Kuchibhotla died, the store’s employees brought meals every day to friends and family gathered at the house.

One May evening, Dumala and her parents went to the grocery store to pick up ingredients for a traditional chickpea dish. Dumala pushed an empty cart down the first aisle toward the produce, unprepared for what would happen next. She stopped, almost involuntarily, in front of a crate of miniature eggplants. The sigh was audible, the sadness palpable.

“This was his favorite food,” she said out loud. “It didn’t matter how you cooked them, he loved any recipe made with eggplant.”

Dumala lingered, lost in the memory of the simple act of baking her late husband’s favorite dish.

John Eligon contributed reporting.

© 2017 New York Times News Service