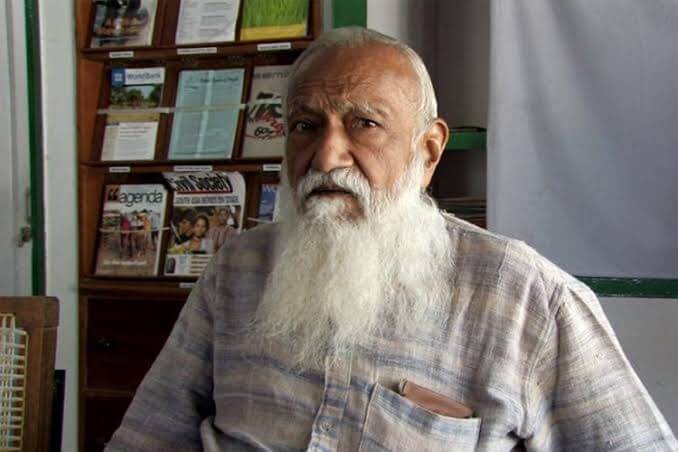

For G.D. Agrawal, the Ganges River was a unique gift that he described as India’s very soul. On Thursday, his crusade to conserve it ended in his death.

Agrawal, 86, a pioneering environmental activist, died after a nearly four-month hunger strike which he began in late June to pressure the Indian government to take a series of actions to rejuvenate the Ganges.

During Agrawal’s fast to draw attention to the plight of the river, he reportedly drank only water with honey and lemon juice.

His death is a sensitive topic for India’s government, which has pledged to clean up the Ganges, a river considered sacred in Hinduism. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s own constituency is in Varanasi, an ancient pilgrimage city which sits on the banks of the Ganges.

The river is revered by many Hindus, who believe bathing in its waters can bring healing and spiritual redemption. But the 1,500-mile long river has become a dumping ground for industrial effluents, agricultural by-products and human waste. Its waters are not only polluted but also meager compared to their prior flow, a situation Agrawal sought to reverse.

Before starting his fast, Agrawal wrote to Modi with a list of demands: pass legislation to clean and revive the river, cancel all hydroelectric projects on the upper reaches of the Ganges, ban deforestation and sand mining along the river and establish an independent body to oversee its management.

The government sent a minister to meet with Agrawal and persuade him to give up his fast, but he refused so long as his demands were not met.

“I have no qualms about giving up my life,” he wrote in a letter to Modi in August. During the Modi government’s time in office, it had taken “not even a single action” toward rescuing the river, Agrawal wrote.

On Thursday evening, Modi expressed his condolences on Twitter and saluted Agrawal’s passion for the environment.

Over the course of his life, Agrawal was an engineer, a professor at one of India’s most prestigious universities, a pollution regulator, an entrepreneur and finally a renunciate: in 2011, he joined an order of Hindu monastics in the northern state of Uttarakhand and took the name Swami Gyan Swaroop Sanand.

As a young man, he did graduate work at the University of California Berkeley. He later taught at the Indian Institute of Technology at Kanpur and served as a member of the Central Pollution Control Board of India.

Together with S.K. Gupta, his former student, Agrawal helped build Envirotech Instruments, the first firm in India to offer locally-made devices for monitoring air pollution.

Agrawal went on to mentor a host of prominent environmental lawyers and activists in India. Following a trip to the Himalayas in 2006, Gupta said, Agrawal became deeply distressed by the state of the Ganges River and decided to devote himself to rejuvenating it.

After Agrawal undertook two previous hunger strikes in 2008 and 2009, the Indian government acceded to his demand that it cancel a hydroelectric project on the Bhagirathi River, one of the sources of the Ganges. But future victories proved elusive.

Gupta, his former student and friend of 50 years, said he spoke to Agrawal on Thursday just before he died at a hospital, where he was taken when his condition deteriorated.

“He advised me to keep up the battle,” Gupta said. “He said, ‘I have lost, but maybe you can fight.'”

(c) 2018, The Washington Post