Perched high in the Himalayas, near India’s border with China, the tiny town of Leh sometimes seems as if it has been left behind by modern technology. Internet and cellphone service is spotty, the two roads to the outside world are snowed in every winter, and Buddhist monasteries compete with military outposts for prime mountaintop locations.

But early each morning, the convenience of the digital age arrives, by way of a plane carrying 15 to 20 bags of packages from Amazon.com. At an elevation of 11,562 feet, Leh is the highest spot in the world where the company offers speedy delivery.

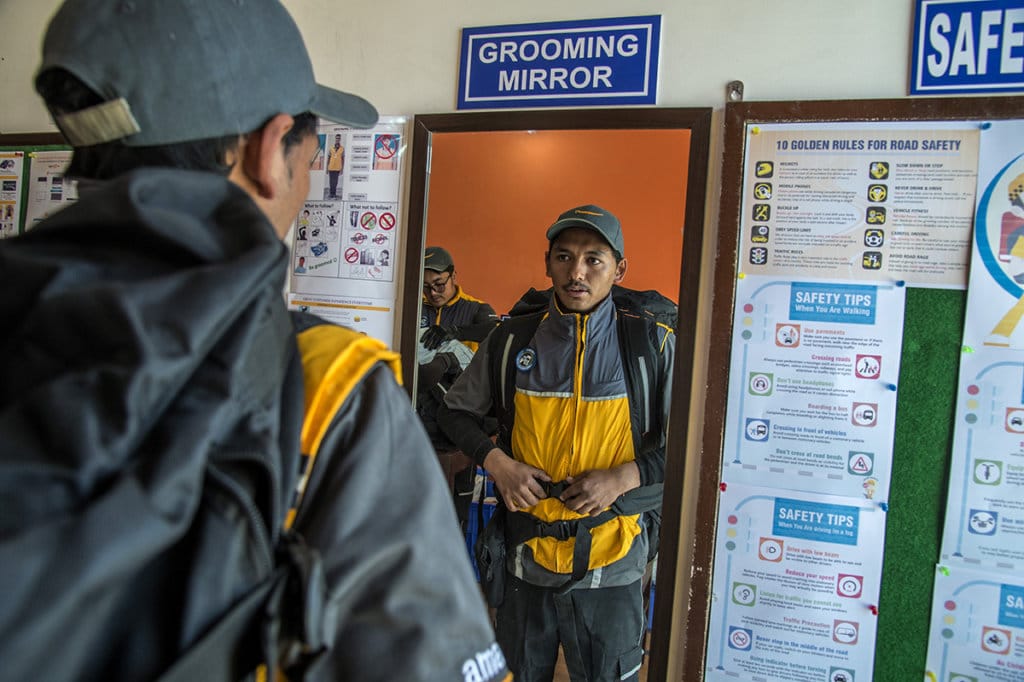

When the plane arrives from New Delhi, it is met by employees from Amazon’s local delivery partner, Incredible Himalaya, who then shuttle the packages by van to a modest warehouse nearby. Eshay Rangdol, 26, the nephew of the owner, helps oversee the sorting of the packages and delivers many of them himself.

The couriers must follow exacting standards set by Amazon, from wearing closed-toe shoes and being neatly groomed to displaying their ID cards and carrying a fully charged cellphone.

Amazon began offering doorstep delivery in this region last fall, as part of an effort to better serve the remotest corners of India. Sales volume in Leh is up twelvefold since Incredible Himalaya took over deliveries from the postal service, which was much slower and required customers to pick up packages at the post office.

Local delivery partners like Incredible Himalaya are vital to the U.S. company’s global strategy, especially as it tries to diversify beyond traditional package delivery companies like UPS or FedEx. Last week, Amazon announced a program to entice more small businesses to join the company’s delivery network in the United States.

Leh is geographically and culturally close to Tibet, a region controlled by China. Buddhist monasteries tend to the religious needs of the town’s 30,000 residents, while military units guard the still-disputed border with China.

A motorcycle makes it easier for Eshay Rangdol, a courier for Amazon, to get around, especially with all the bumps — not to mention the cows — in the roads, in the Himalayan town of Leh, India, May 22, 2018. Photo Credit: Atul Loke/The New York Times

Rangdol and the other couriers get to the shoppers via motorcycle and scooter. When the snow is heavy in the winter, they will occasionally use a car. But two wheels are generally better than four to navigate Leh’s narrow, bumpy roads and dodge the ubiquitous cows.

Skalzing Dolma, a frequent Amazon customer, was Rangdol’s first stop on a recent day, receiving a delivery of bedsheets and eye shadow.

Dolma has bought everything from clothing to kitchen appliances on Amazon and estimated that she has spent a total of 100,000 rupees, or around $1,500, on the site. With few choices in Leh stores, cosmetics and clothing are popular categories for Amazon here.

Orders typically arrive in five to seven days, slower than the two-day delivery that Amazon’s big-city customers receive but quicker than the monthlong journey they often took with the post office.

With a baby due in July, Rigzin Dolker, who used to work at call centers in Delhi, finds Amazon to be far more convenient than trekking into town. She has been buying baby clothes and makeup from the company.

Fortunately for Amazon, local soldiers and monks are big customers. Thinley Odzer, a monk at the tiny Kartse Monastery, received a backpack. In the past, he has bought mobile phone cases and parts for his motorbike.

Leh hardly seems like the kind of market that would appeal to a global e-commerce giant like Amazon. Internet service — essential to placing an order — cuts out frequently during the best of times and goes down entirely for weeks or months during winter, when the trunk line to Srinagar, the state capital, is damaged under the snow.

But Amazon takes the long view. E-commerce is spreading globally, and India is a prime battleground, where customers are just beginning to shop online and loyalties are not yet established. Walmart recently announced plans to buy a controlling interest in India’s leading e-commerce company, Flipkart, allowing it to challenge Amazon directly for the wallets of Indian consumers.

Amazon may never make money shipping products by air to customers in Leh. But the idea is that profits from dense urban areas like Mumbai and Delhi will subsidize service to more remote ones.

“We want to make delivery convenient to where our customers are,” said Tim Collins, Amazon’s vice president of global logistics. “Over time, the economics will work themselves out.”

The strategy rankles Leh merchants like Nawang Shispa, owner of Tsering Electronics, who said his sales of phones and accessories had dropped 10 percent since Amazon started quicker delivery to the community.

Still, his salesmen compensate. One of them sold a new Oppo smartphone to Jigmat Amo, 16, by slightly undercutting Amazon’s price. Amo said she was a bit leery of Amazon after buying a handbag and a pair of ballet shoes from the site that did not look like the pictures.

Liyaqat Ali, owner of the Singay General Store in the main town square, figured that there is room enough for both him and Amazon. He does a brisk business selling groceries and sundries like diapers, which people typically need right away.

“Amazon is new to Leh and the internet is not so good,” he said. “And if you order something like diapers, you have to wait a week to 10 days.”

Eshay Rangdol, a courier for Amazon, uses his motorcycle to deliver packages in the Himalayan town of Leh, India, May 22, 2018. Photo Credit: Atul Loke/The New York Times

Rangdol said that in addition to delivering packages and managing the delivery warehouse, he taught people how to order on Amazon.

“Before I joined Amazon, my friends called me Eshay,” he said. “Now they call me Amazon.”

Working with the company is certainly better than his previous job leading tourists on long treks up cold mountains — although he still has to do a bit of climbing with a heavy pack.

© 2018 New York Times News Service