It is a marquee name for a marquee venture.

Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase, the powerful triumvirate that earlier announced its hope to overhaul the health care of its employees and set an example for the nation, said Wednesday that it had picked one of the country’s most famous doctors to lead the new operation.

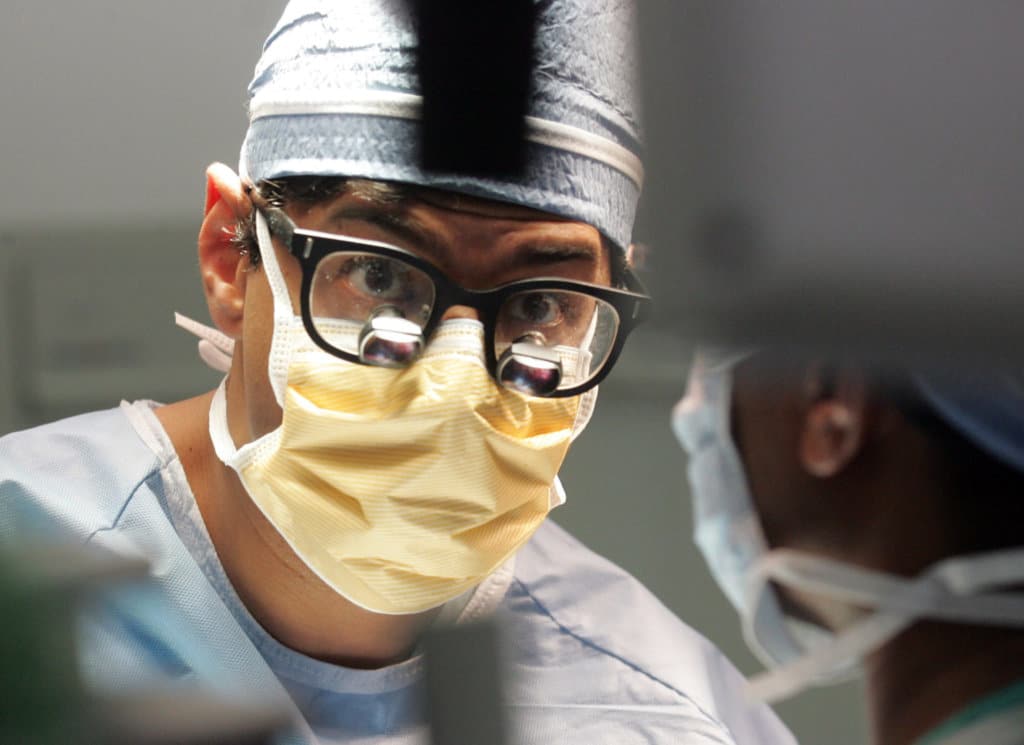

Dr. Atul Gawande, a Harvard surgeon and staff writer for The New Yorker magazine, will become chief executive of the new company, which will be based in Boston, on July 9. He said he was not stepping down from his current medical and other duties to take the job.

The choice of Gawande, a highly respected doctor and writer on health care, was met with surprise because he has little hands-on experience running a large health care organization, unlike some of the boldface names that have been floated as possible candidates.

“He’s such a well-known health care luminary and keen observer, but this is a big leap,” said Dr. Lisa Bielamowicz, a co-founder of Gist Healthcare, a consultancy in Washington. “He hasn’t led a huge team or company.”

By moving into health care, the three corporations had signaled a widespread frustration, shared by many American businesses, with the country’s convoluted, high-cost medical infrastructure. In forming the new venture, the alliance said it would “operate as an independent entity that is free from profit-making incentives and constraints.”

As desperate as employers are to see significant change, the alliance’s three chief executives — Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett, and JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon — have offered little detail as to what they want, and their efforts so far have been received with skepticism. Corporations have long tried to reduce the cost and complexity of medical care, but making changes requires taking on powerful interests like big hospitals and insurance companies that want to preserve the status quo.

The three companies represent roughly 1.2 million employees scattered across different markets, giving them little immediate leverage with health plans and hospitals.

The selection of Gawande, who has spoken out loudly and clearly against some of the issues with health care, is the first concrete step taken by the three to fulfill their promise to shake up the system, which Buffett has described as “a tapeworm of American economic competitiveness” because of spiraling costs that continue to eat up more of the country’s gross domestic product.

“We said at the outset that the degree of difficulty is high and success is going to require an expert’s knowledge, a beginner’s mind, and a long-term orientation,” Bezos said Wednesday. “Atul embodies all three, and we’re starting strong as we move forward in this challenging and worthwhile endeavor.”

There is little doubt that Gawande will be able to outline what he has said he believes are the system’s failings. “Tapping Atul Gawande to head the new venture is a very positive sign,” said Brian Marcotte, the chief executive of the National Business Group on Health, which represents large employers. “He is a thought leader, thinks outside the box, and is passionate about fixing what ails our health care system.”

Gawande is a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School and a practicing surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“This work will take time but must be done,” Gawande said in a statement. “The system is broken, and better is possible.” He declined to be interviewed.

He is also the executive director for Ariadne Labs, a joint project by Brigham and Women’s and Harvard to further the adoption of measures that aim to improve patient safety, like surgical checklists.

In a letter to friends and colleagues, Gawande said his role as chief executive “will not require me to leave Ariadne Labs, Brigham Health, or Harvard. My plan is to transition from executive director of Ariadne to chairman, while remaining a surgeon on staff at the Brigham and professor at Harvard. I will also continue to write, including for The New Yorker magazine.”

His articles, while influential, have not been immune to criticism. His 2009 New Yorker piece, “The Cost Conundrum,” which looked at unnecessary care in McAllen, Texas, by comparing spending patterns around the nation, was required reading in the Obama White House. But McAllen was a hot spot of medical fraud, and subsequent studies showed that the places identified as low-cost under Medicare could actually be high cost for those who are privately insured.

Gawande was chosen for the position after leaders at Amazon, Berkshire and JPMorgan interviewed many professionals, Buffett said. The companies seemed to struggle publicly to find an executive, with prominent leaders like David T. Feinberg, the chief executive of Geisinger Health System, the innovative group in Pennsylvania, saying they were not taking the job.

While Gawande does not have business experience, he has spent his career focusing on how to improve care for the sickest patients, said Dr. Bob Kocher, a venture capitalist who advised President Barack Obama on health care policy. He pointed to Gawande’s ability to attract other individuals to the venture.

“He understands the health care system as an insider,” Kocher said. “He has been a truth-teller.”

But Kocher said that Gawande’s public health experience in emphasizing preventive care is unlikely to yield the immediate savings companies like these three want. “He is going to have to come up with a whole new tool kit,” he said.

The challenge he and the rest of the country face is how to overcome the pricing power of big hospital groups that dominate certain markets, and drug companies, Kocher said. Employers have also been resistant to limiting the choice of hospitals and doctors for their workers.

Instead of finding someone who has experience running a health care business, “they picked a very splashy name,” said Craig Garthwaite, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

The fact that Gawande is not devoting all of his energies to the venture makes Garthwaite more skeptical. “It starts to feel fundamentally unserious if you’re not hiring a full-time CEO,” Garthwaite said.

“If you’re transforming health care, you’re reshaping the economy of Germany, effectively,” he said. “It’s not a part-time gig.”

© 2018 New York Times News Service