Five people were killed by a mob in India on Sunday after rumors spread on social media that they were child traffickers, the latest in a string of lynchings tied to fake social media messages that have left officials stunned and grappling with ways to control the rising violence.

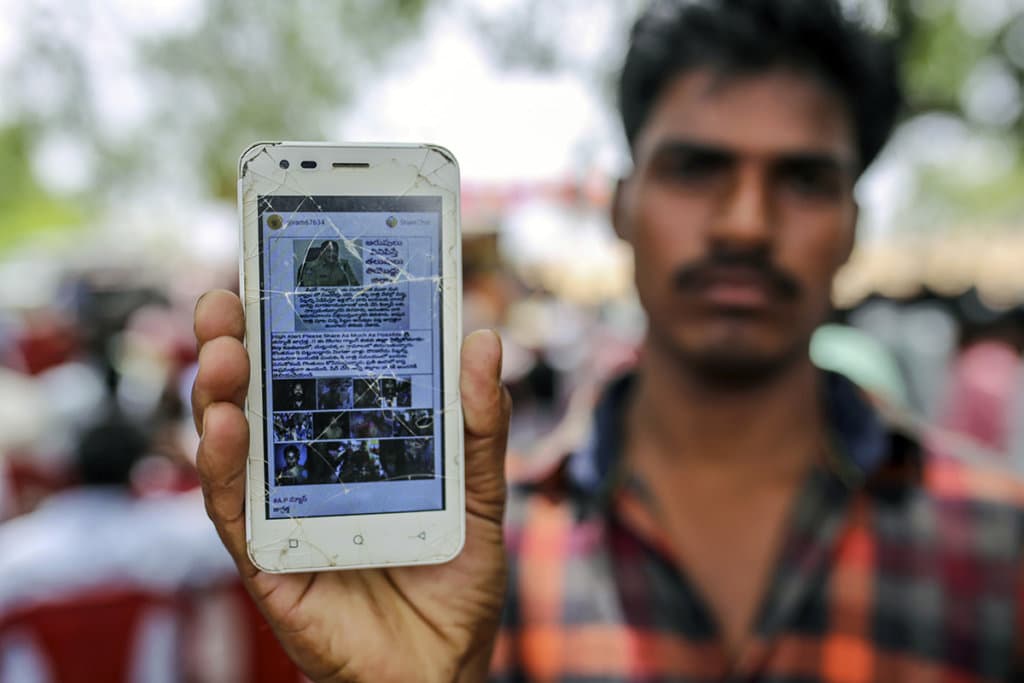

More than a dozen people have been killed across India since May in violence fueled mainly by messages on the WhatsApp service. The cases largely feature villagers, some of whom may be using smartphones for the first time. Inflamed by fake warnings of child trafficking rings or organ harvesters, they have attacked innocent bystanders and beaten them to death.

Governments around the world are considering laws and controls against fake news in the wake of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the rise of hate speech. Such reactions have raised free-speech concerns. But the spread of fake news, a global scourge, has been particularly pernicious in India, where legions of new, inexperienced smartphone users send billions of messages a day on WhatsApp, which has more than 200 million users in India, its largest market.

As India’s government weighs what to do, local authorities have been left to tackle fake news as best they can, issuing warnings and employing low-tech methods such as hiring street performers and “rumor busters” to visit villages to spread public awareness. One such “rumor buster” was killed by a mob Thursday in the eastern state of Tripura.

“We are trying to counter the misinformation by aggressive campaigning on social media, WhatsApp and local TV channels,” said M. Ramkumar, the superintendent of police in Dhule, a district in western India. It was there that five nomadic beggars were beaten to death Sunday by villagers, who thought they were child kidnappers.

“We want to convey the message that all rumors are false and they should not fall prey to them,” Ramkumar said.

In recent days, officials of WhatsApp – owned by Facebook and based in Menlo Park, California – have introduced a new function that allows administrators of groups to control which members can post messages, and the company is testing a plan to label which messages are forwards. WhatsApp is expanding outreach in India as its 2019 general election looms and political parties are signing up “WhatsApp warriors” by the thousands – who, in some cases, spread incendiary content themselves.

“WhatsApp is working to make it clear when users have received forwarded information and provide controls to group administrators to reduce the spread of unwanted messages in private chats,” said a spokesman for WhatsApp, Carl Woog. “We’ve also seen people use WhatsApp to fight misinformation, including the police in India, news organizations and fact checkers. We are working with a number of organizations to step up our education efforts so that people know how to spot fake news and hoaxes circulating online.”

Unlike Facebook – where users can be tracked and shut down for posting content that violates its standards – WhatsApp content is more difficult to monitor because messages are encrypted between users. Still, critics say, it can and should do more in a country where hundreds of thousands of people are coming online for the first time.

“The police are always going to be at a loss because the scale of WhatsApp usage is going to be difficult to contend with and they don’t have the manpower,” said Nikhil Pahwa, a technology expert. “The platform itself needs to evolve.”

Pahwa argues that WhatsApp’s forwarded messages should be tagged with the originating number, to make it easier to crack down on misuse and discourage users from creating bad content.

Meanwhile, Google announced last month that it is expanding an existing program for journalists in India to help train 8,000 reporters in seven languages to spot and expose fake news generated in the country’s “specific misinformation ecosystem,” according to Irene Jay Liu, the head of Google News Lab for the Asia-Pacific region, Google’s largest such effort.

The Indian government’s attempts to combat the problem have been fraught. In April, a circular from the Information and Broadcasting Ministry proposing stiff penalties for journalists who post fake news was pulled in less than 24 hours after widespread outcry.

In Tripura, three people were killed last week in violence fueled by the death of an 11-year-old boy on June 26. Rumors on WhatsApp that he was the victim of organ harvesters were reinforced by Ratan Lal Nath, a leader of the governing Bharatiya Janata Party, who showed up at the boy’s home to falsely allege that the child’s kidney had been cut from his body by organ traffickers, a video shows. Police later dispelled this fiction, but the damage had been done.

The state’s Information and Cultural Affairs Department hired “rumor busters” to control the subsequent violence, including Sukanta Chakraborty, 33, a tabla musician with a sonorous voice who was paid about $8 a day to travel from village to village in a van equipped with a loudspeaker, warning about the dangers of fake news. He and two others were beset by a mob wielding bricks and bamboo sticks in a crowded market Thursday.

“They killed him. He was pleading to the mob that he was only doing his duty. No one listened to him,” Tanushri Barua, Chakraborty’s wife, said in a telephone interview. “What was his fault? Now there is nothing left.”

Farheen Fatima contributed to this report.

(c) 2018, The Washington Post