The gifted and iconoclastic star of Ray’s classic Ghare Baire and David Lean’s unforgettable Passage to India, Victor Banerjee, once acerbically commented: “Theater is a sacred communion with the muse, while cinema is, at best, a fantastic one-night stand!”

Another veteran actor asserted: “Most Bollywood stars are reaping the fruits of good fortune — kismet, naseeb — right time, right place, right connections with an audience-base, bred and buttered on low-browed, mindless hamming that goes for great acting! No wonder, neither our stars nor cinema feature anywhere in world cinema.”

Victor Banerjee as Khwaja Saheb in Meherjaan: “Theater is a sacred communion with the muse, while cinema is, at best, a fantastic one-night stand!”

Bombastic and dismissive as these barbs may be, how come stage actors, for all their training and brilliance, never make it, either in Bollywood or Hollywood? Acknowledged greats of the British theater — Laurence Olivier, Richard Burton, Paul Scofield, Alec Guinness, Michael Redgrave, Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud—all made the trek to Tinsel Town, inviting appropriate awe. But on screen, they rarely matched the star-power or popularity of Rock Hudson, William Holden, Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Kirk Douglas or Gregory Peck, right? Similarly, for all their acting talents, the likes of Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri or Pankaj Kapoor have never really lit up the screen or connected with mass audiences on the same scale as Amitabh Bachchan, Shahrukh Khan, Salman Khan, Dharamendra, Hrithik Roshan or Akshay Kumar.

So why this inverted snobbery, superiority complex and condescension toward movie-acting?

Brilliant teacher-turned screen actor and alum of the National School of Drama Adil Hussain — Life of Pi, English Vinglish, Lootera — argues that “Bollywood is more about waiting than acting. You wait for your shot for five hours and then if you are lucky, you get maybe five minutes of acting!”

He also has coined a unique name for Bollywood acting — Fedex! — “Once Action is yelled, you need to instantly perform and move on ….”

Pankaj Kapur in Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola.

He believes that despite some brilliant screen actors — Amitabh Bachchan and Dilip Kumar — Bollywood is not conducive to good acting, and mediocrity is just fine to garner one fame and riches. “Posturing is the name of the game and mass audiences conditioned to this nautanki lap it up. Theater is more real and pure, but since our audiences have been corrupted beyond measure, theater actors find limited acceptance in this space,” he says.

Renowned Kolkata-based theater director Sohag Sen says: “I believe, involvement and internalization of your role and presentation in a focused and compelling manner is the same in both platforms. The challenge is, since they are separate platforms — one is raw and basic, the other technology-driven — to intelligently understand and adapt one’s skills to suit the respective mediums.”

Shyam Benegal: “It’s not about superior or inferior, but about who is in control. In the theater, the actor is the king, storm-center and focal point.”

Mumbai-based theater actor and director Bharat Dabolkar is partial toward theater: “You see theater is the real thing. To remain in character for two hours, with no luxury of re-takes or technological advantages and facing a live audience, day in and day out, separates the boys from the men … and the bouquets and brickbats that arrive instantly is a different feeling altogether.”

Dabolkar concedes, however, that film acting too has its challenges, where an actor can well begin with Scene 36 and a week or month later do Scene 18. It is the actor’s responsibility to stay in continuity and character. Not an easy task. However, support systems and technology are always there to help — something that is totally missing in theater.

“It’s like after all the coaching and discussions with your team experts, you go out to the middle to bat. You are all alone and it’s you against the bowler. You sink or swim,” he says.

Renowned film critic Saibal Chatterjee offers a different spin: “The reason why brilliant theater personalities like Naseer, Om, Pankaj and gang have not been able to make the cut in mainstream Bollywood is because it’s a different template. They find it very difficult to indulge in the mandatory over-the-top, jatra kind of histrionics, trained as they are to underplay and be realistic. Naseer has admitted time and again that he found it both awkward and embarrassing and just couldn’t manage to square off with that brand of performance … and didn’t really feel like conforming to win mass acceptance.

“The result is that he continues to be an icon for the evolved and discriminating. His latest film Waiting once again re-enforces his stunning gifts as an actor par excellence, but ignored by the devotees of the mega-stars.”

Chatterjee however admits that it’s silly to summarily dismiss screen actors because a Govinda or SRK bring a unbelievable believability, excitement and energy to make the craziest scenes, audience-friendly, something theater actors would find difficult.

Eminent Bangalore-based theater director Ranjon Ghoshal takes a more nuanced view: “It’s true about the inverted snobbery that many theater actors feel about cinema and that’s largely because they are on the side of acting defining linear truths and realism, divorced from the large doses of glamor, star-power and other distractions that kill the essence of a great performance. Bollywood screen stars, mostly, represent the sizzle not the steak!”

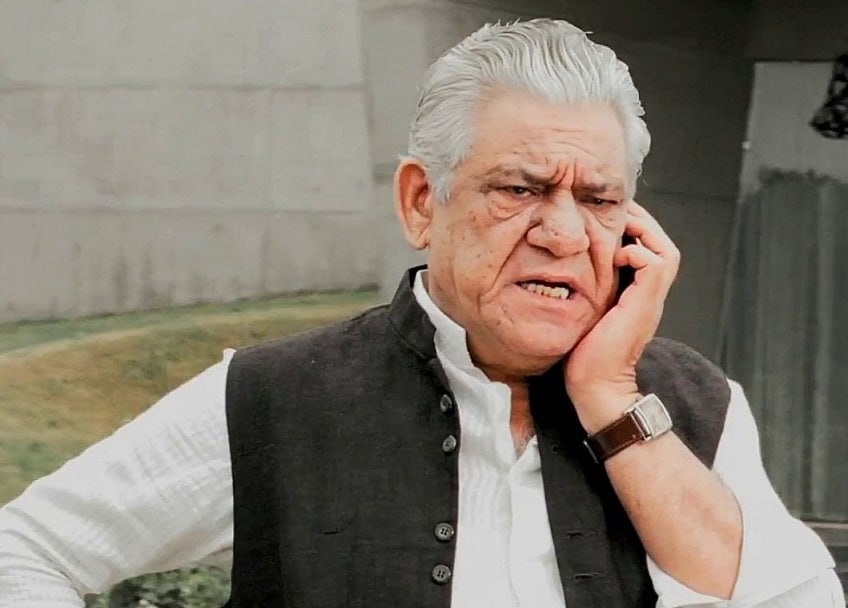

What better way to wrap up the debate than tune-in with two illustrious icons of Indian cinema, veteran film-maker Shyam Benegal and Om Puri, poster boys of parallel cinema that swept India in the 1970s.

The father of the New Cinema that charmed the audiences of the 1970s, Benegal is clarity personified: “It’s not about superior or inferior, but about who is in control. In the theater, the actor is the king, storm-center and focal point. It is he who rules and he alone who shapes and forms the performance by intelligently pitching it to a level that connects convincingly with the live audience. Sure the director and writer play a part, but ultimately it is the actor who makes it happen. The theater, hence, is totally the actor’s medium. In cinema, it is totally the director’s medium. It is his vision and every move is directed and choreographed under his supervision. Great screen actors interpret his vision, but even by mimicking the director’s direction, a fair level of competence can be achieved.”

Benegal is however quick to concede that gifted actors quickly accept and learn to adapt and realize that “the camera is their audience and the pitching style is totally different with the dynamics of screen acting offering its own unique compulsions and demands.”

An actor of great power and intensity whose performances scorched the scene every time he appeared, Om Puri says: “For me, cinema is the child of the theater. All other aspects were borrowed from the theater because that was the only reference point. With time, it developed its own road map and with technology stepping in, it really took off.”

Regarding which is superior, Puri demurs, arguing that both have their own challenges:

“In theater, it’s you and the audiences — no retakes or technology backup. In cinema, you have to evoke and build-up believable intensity amidst tons of distracting props — lights, people, wires — in a manner that is convincing. You have to concentrate and focus hard on the lines and mood of the scene, blocking off everything else, unlike theater, where there are no such distractions. Of course, you have the luxury of retakes, but that challenge remains.”

Regarding Bollywood’s corrupting influence, the star of Akrosh and East is East, believes it’s up to the makers “whether you want Bhimsen Joshi or Daler Mehendi!”

At a personal level, Puri prefers cinema, simply because “I can reach out to many more people across the globe than theater. However, theater does provide a deeper connect and that definitive moment of truth that cinema can seldom match, because people mostly associate movies with entertainment, glamor and technology.”