The hilltop forts of Rajasthan in northwest India are among the most poignant human-made environments in the world. An ambiance of strife-torn, centuries-old power and ineluctable decay commingle there with softly colored decorations, natural beauty and a sense of secluded elevation from the earthly hubbub. The effect, at least in my brief experience, is dislodging: You come away changed.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston has not succeeded in transporting one of these forts to Texas – but it has done the next best thing. Working with an international team, it has mounted a landmark exhibition of paintings, textiles, weapons, jewelry, palanquins, thrones, robes, carpets, sunshades, fly whisks, and foot scrapers – more than 300 objects in total – drawn mostly from the huge collections of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust at Jodhpur.

The show has something for everyone. It kicks off with life-size animal mannequins sumptuously adorned for a spectacular wedding procession. It concludes with a Stinson L-5 Sentinel aircraft, or “Flying Jeep,” and a 1927 Rolls-Royce Phantom, custom-built for use by the female members of the court of Maharaja Umaid Singh. The car comes replete with blue “purdah” glass (so the women would not be seen) and a search light for – what else? – tiger hunting.

But it’s not, fundamentally, that kind of show. Rather, it’s a thoughtful, stately and scholarly exhibition, filled with objects of almost unbelievable refinement, most of which have never left Jodhpur, let alone India. Among them are dozens of Mughal and Rajput paintings; a rare Mughal tent; a matchlock pistol with five barrels; a brilliant display of colorful turbans; swords and punch daggers galore; a dazzling ornament of diamonds and emeralds; and many carpets and embroidered textiles.

The objects from the Mehrangarh Fort Museum are complemented by loans from Queen Elizabeth II, the al-Sabah Collection in Kuwait and the Umaid Bhawan Palace, Jodhpur. Among those from the latter is a wooden model, coated in silver, of Mehrangarh Fort, made in 1930 to 1931. Its uniform, gleaming surface highlights the way in which the building, constructed from red sandstone mined by hand from the same site, seems to emerge as if organically from the rocky plateau.

Construction on the fort, which is really a series of interconnected palaces, began in the 15th century. In the 20th century, five years after India gained independence, it was inherited by a 4-year-old boy. Gaj Singh II, the maharaja of Marwar-Jodhpur, who was educated in England and then returned to his inherited responsibilities, eventually establishing a museum at Mehrangarh Fort. It now attracts more than a million visitors per year.

Although “Peacock in the Desert” appears to tell a story about a single ruling clan from a desert landscape in a limited region of the subcontinent, it is in no way a show about isolation. Rather, it is shot through with cosmopolitanism, revealing countless forms of hybrid beauty, blended belief and convoluted self-assertion.

Jodhpur was established as the capital of the desert kingdom of Marwar by the 15th century. Its founders, a Hindu clan known as the Rathores, had been harassed out of their homeland further north two centuries earlier. The city’s gathering wealth grew out of its position at the crossroads of trade routes.

That enviable position also made it vulnerable, however, to two expansionist empires: First the Mughal, which exerted shifting degrees of control from the mid-16th to the mid-19th centuries; and then the British, who ruled from 1858 to 1947. Both periods saw the Rathores, a proud, martial people, resist, yield, and continually jockey for power, with the foreign rulers and with other Rajput territories.

More than military victories and defeats, strategic marriages and exchanges of gifts played a key role in molding everything about the region’s culture, from religion and language to warfare, architecture and artistic pursuits. Women – despite the strictures of purdah and the establishment of separate female courts, known as “zenana”– played catalyzing roles as patrons and collectors, bringing new customs, art forms, and tastes into court life.

The objects reveal different aspects of Hindu, Muslim and Western European traditions. Influence ran both ways: The Rathores, it’s obvious, were greatly influenced by Mughal art and architecture. But the Mughals also learned from – and participated in – the Hindu culture of the Rathores.

Rathore rulers and their courts spent long periods away from Jodhpur, both at the Mughal court and on military missions. One of the highlights of the show is the Lal Dera, an elaborate, ruby-colored tent from the late 17th or early 18th century. Believed to have been captured during a surprise attack on the camp of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, it is a square pavilion with a flat roof at the center, held up by four poles, and a veranda under sloping roofs all around it.

Yes, it’s just a tent. It certainly doesn’t compare with Mehrangarh Fort. And yet . . . wow! Decorated with cream and cherry-colored stripes, with walls of silk velvet in plum and magenta and borders of sea green, all of it embroidered with floral motifs, it would have cost a fortune. So if it was indeed loot (and there is no way, as Peter Alford Andrews points out in the catalogue, the Mughals would have offered a royal tent as a gift), it was very valuable – both materially and symbolically.

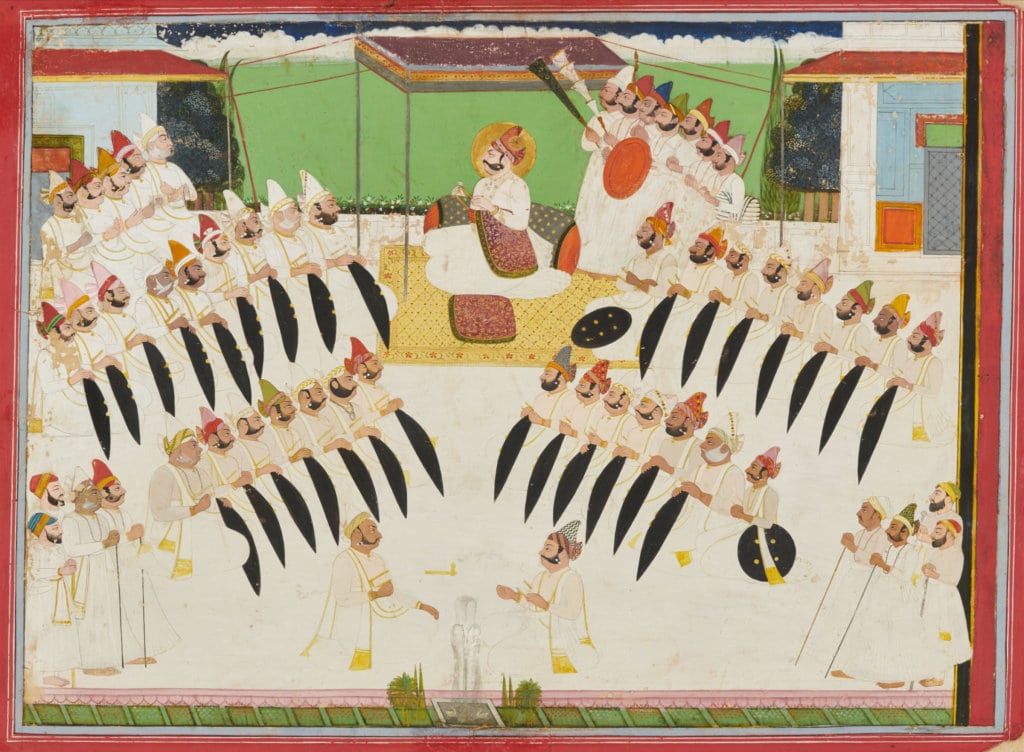

The paintings include a number of Mughal miniatures from the collection of Queen Elizabeth II. The word “miniature” is misleading: We are talking about some of the greatest, most ambitious paintings in world art. They show scenes from the Mughal court with members of the Rathore clan always visible and close – but subservient – to the emperor.

The Rajput paintings, mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries, lack the advanced finesse of the 17th-century Mughal style (which derived from Persia). But they are precious and lovely in their own way and steeped in local atmosphere. They tend to employ larger areas of vivid color: Midnight blue, a dusky purple, a spreading green warmed by tinges of yellow.

Great Rajput painters such as Dalchand, working in the first quarter of the 18th century, portrayed Rathore rulers in their courtly settings, exuding characteristic Rathore virtues: not just martial vigor but also generosity, chivalry, a sincere yet still nonchalant interest in music and leisure, an aura of discerning connoisseurship.

One notable painting is an 18th-century double portrait of Maharaja Ajit Singh and his son Bakhat Singh. Both men are set against a ground of drenching turquoise. Bakhat Singh, shown receiving a garland from his father, looks innocuous enough. But the story behind the image suggests otherwise, recalling a plot line out of Shakespeare or “Game of Thrones.”

When Maharaja Jaswant Singh died in 1678, his two potential heirs were already in the grave. The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb filled the resulting power vacuum and occupied Jodhpur for almost 30 years. Jaswant Singh, however, had left behind two pregnant wives. The wives were secreted away by Marwar nobles. Only one of the babies, Ajit Singh, survived. The nobles waited until Aurangzeb died in 1707, then installed Singh on the throne.

Singh restored the damage done to Mehrangarh Fort and Jodhpur’s Hindu temples by Aurangzeb, an austere Muslim, and he groomed his two sons to take on royal responsibilities. However, one of them was impatient. On the night of June 23, 1724, when he was just 18, Bakhat Singh murdered his father as he slept in his royal chamber in Mehrangarh Fort.

The painting of Ajit Singh presenting his treacherous son with the garland was made more than two decades after this patricide. Catherine Glynn, in her catalogue essay on Jodhpur painting, writes that it was probably commissioned by Bakhat Singh in an effort to establish his dubious legitimacy.

“Peacock in the Desert” is not huge. It’s easy to navigate. But it is dense with delights and revelations.

It might also present a model for future efforts by Western museums to engage with Indian culture – and indeed the cultures of other countries. The exhibition was seen to fruition by Mahrukh Tarapor, senior adviser for international initiatives at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Karni Jasol, director of the Mehrangarh Fort Museum. Most of the objects and much of the scholarship have come from India.

The show is dedicated to the memory of Martand Singh (1947-2017), known affectionately as “Mapu” – a former chairman of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, director of the Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad and chief consultant for this exhibition until his death.

After “Peacock in the Desert” ends in Houston, it travels to Seattle and then Toronto. See it, if you can.

“Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur” Through Aug. 19 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Oct. 18-Jan. 21 at the Seattle Art Museum; March 9-Sept. 2, 2019, at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

(c) 2018, The Washington Post