Magazine

Voice of the Voiceless

Edward Said taught us to speak truth to power.

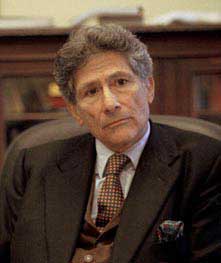

| Edward Said died in late September. A distinguished professor at Columbia University, an extraordinarily formidable theorist, philosopher and teacher, an exemplarily articulate participant in our public life, one of the strongest voices in support of Palestinians in this country, a consistent and thoughtful critic of the Israel, an inspiring human being and a powerful spokesman for humanism, he passed away after a long, heroic and a debilitating struggle with a form of leukemia.

Edward Said was born in Jerusalem, Palestine, brought up in Egypt as his family left the troubled land, and educated for most of his life in the United States, where he worked and taught.

Death comes eventually to all of us. At this writing several other deaths have featured prominently in the media. We have seen and heard glowing tributes to Robert Palmer and George Plimpton. May we bless their souls, but it seems there is greater celebration for those who sing the tune of power and make little difference in the alleviation of human suffering. It is surprising the praise we heap on dead people, especially on slow news days. On the other hand, there is little by way of remembrance of Edward Said in the corporate media. As we watch the media spectacles of selective blessings, we need to take a moment to remember Professor Said. To him we owe a deep sense of gratitude. For all of us, who live outside of the “homeland” of our birth and history, search for our souls in the land, which deprives us of the same, and search for our spine to take a stand against power and for justice, the name and life of Edward Said should be remembered withreflection. His was a truly cosmopolitan and worldly soul, which has contributed immensely to our own identity and integrity. Edward Said has been extremely influential to Indian students, professors and academic world in general. He deeply appreciated the political edge of the Subaltern studies movement in India, where our historians focused on that part of history which was submerged by the oppressive presence of dominant powers. He was a brilliant thinker of exile. He transformed his own sense of physical exile, a separation from his land of birth and a perpetual sense of unhappiness in the land of his residence into an eloquent perspective of exile as a political, psychological position. He cherished the proposition that one can never be content to be “home,” as it brings a lack of perspective, a loss of anchor for one’s conviction and a death of one’s soul. Many Indians have been deeply influenced by his writings, and some of them have written for this magazine. Most importantly, it is what he did as a fighter for the cause of justice that remains a living inspiration for all of us. Edward Said fought for the cause of Palestinians. Although he was a world-class intellectual, he wrote in the popular press, he carried his debates to newspapers, magazines and the media. Unlike other academics, who are often one-note whiners, his work was astoundingly inspiring. He brought his theoretical and philosophical understanding to real life issues of oppression and injustice. He was one of the strongest critics of the policies of the United States and Israel. He believed that Palestinians and Israelis must live together in a binational single state. Although he changed from being a strong supporter of an independent and separate Palestine, his basic convictions never changed. His voice was fearless and often derided or denounced in the academic world. Professors and intellectuals in this country admired his theoretical writings, but detested (sometimes with an impassioned hatred) his involvement in the political cause of Palestine. He did this despite powerful resistance of the Israeli lobby in this country. He did this despite clear death threats against him and he did this because he believed in justice for Palestinians and in the integrity of intellectuals in this world. He wrote about all of this. His practice and his preaching shaped a generation of scholars here and around the world. Very few people have the courage and the articulate power of bold expression behind their beliefs or convictions. Very few intellectuals live by what they preach and even fewer think outside of their self-contained boxes. Edward Said made intellectuals uncomfortable. He participated in the public debates with an energy that is matched by very few indeed. His works of theory and philosophy were incredibly formidable, impressive and long lasting. His literary output was phenomenal. There is a lesson here. There has always been a lesson here. In the life and work of Edward Said intellectuals should find their calling. These intellectuals who spend a lifetime thinking in narrow specialties should throw away the comfortable securities of their cozy existence and participate in public lives where their knowledge is useful and the causes demand their effort. There is something deeply offensive about an isolated intellectual whose gifts are wasted in search of individual comforts. There is even something insulting when an intellectual preaches social justice and does not have the courage to say one word outside his closed world. Watching the life of Professor Said, this tragic dimension of academic and public life in this country becomes darker and darker. Those who are inspired by the exemplariness of his work, one hopes, will only gather strength as we remember him in the years to come. There is much less innocence in the lives of celebrities who have simply subscribed their lives in the service of power. But in this democratic world, one thinks, it is a gift and a blessing to be sleeping with power. Those writing on the left have been glowing, but one is yet to see the left which speaks of social justice to articulate their mourning at this loss. It is Alexander Cockburn in Counterpunch who brings the spark of the spirit of Edward Said’s soul and admires what needs to be admired. Moments like these are often overtaken by involuntary memories as well. I remember Edward Said as an impeccably dressed handsome man. His taste in clothes, one dares say, was quite discordant with the lives of the musty academic world in which he moved. That did not stop them from wondering how a person with such radical conviction could be so “rich” in his appearance. An accomplished pianist, Edward Said wrote some of the most surprising and sharp essays on music. His concert with Israeli pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim in Israel was memorable for its reach and its accomplishment. The first time I saw him was in Pittsburgh. I went to receive him at the airport as he was visiting the town for a lecture. With a strange combination of excitement, anxiety and eagerness, I rushed toward him as I saw him outside the gate at the airport. He was so taken by the rush at him that he ducked. He explained later that it was the time he was living under death threats and was not used to any enthusiastic or sudden movements in public life. We spent some two hours that day talking. He got visibly animated when I brought up Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the Pakistani/Urdu poet who had written on exile, love and separation. Said noted with great admiration the last days of Faiz in Beirut. When the bombs were falling all around him, and the city was on the verge of destruction, Faiz did not leave his adopted home. He did not want to. He lived by his commitments. As I remember that, I realize the kind of people Said admired. And I say to myself, there is so much to learn from the life of Edward Said. |