Magazine

Matter Of Justice

Vivek Maru brings paralegal services to Sierra Leone's poor.

Vivek Maru has an unusual resume for a cab driver in Sierra Leone. A graduate of Harvard College and Yale Law School, Maru could easily blend in with the clique of expatriate elites that congregate in the capital city of Freetown. Instead, Maru’s old Nissan is routinely stuffed with anyone and anything – including chickens and goats – needing a ride on his way to work.

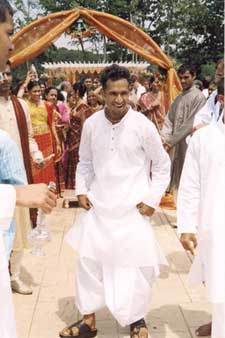

Sierra Leone does not have formal public transportation and private vehicles, like Maru’s, serve the function of local “buses,” simply picking up people off the roadside. “Eeeyooooeeyooo,” Maru unabashedly calls out during an interview in an otherwise quiet New York City Starbucks, imitating his cab driver call. The embrace of local culture is typical of Maru’s character. His informal cab service has earned him loyal local friends and helped him learn the Krio language. It also demonstrates the joy he can experience despite the harsh landscape of Sierra Leone. Dressed in a cotton kurta, with a bike, a preferred method of transportation, parked outside, Maru radiates enthusiasm for his human rights work, which most others would find disheartening.

In 2003, Maru traded his comfortable native Connecticut for a home in one of the world’s most isolated countries, which until 2002 had been ravaged by an 11-year civil war. Committed to social justice causes from a young age, he regularly worked in human rights initiatives throughout high school and college. Many of those experiences were focused on South Asia, particularly since he belongs to the tight-knit Bidada village community in Kutch. He developed a legal services initiative for the poor in war-ravaged Sierra Leone after meeting the organization’s current co-founder. “I know there are people suffering everywhere, even in America,” he explains of his decision to move to Africa, “but the suffering in Sierra Leone is so acute that I feel compelled and actually privileged to be able to make a difference.” The result is “Timap for Justice,” an innovative community-based paralegal program in Sierra Leone, a nation of 5 million people in West Africa. The organization is dedicated to advancing justice services for the poor who find themselves in village courts that apply local customary laws, which often conflict with basic human rights principles. Navigating this legal system can be horrifying and Maru narrates stories of numerous clients who face physical and emotional trauma after being caught up in the justice system. Access to courts also often requires exorbitant fees that can bankrupt the already financially vulnerable.

Under Timap’s model, paralegals from different chiefdoms across Sierra Leone work directly with the poor on cases that range from domestic violence to employment rights. Paralegals help individual clients understand their rights and reach out into communities to urge members to take collective action against widespread problems, like police abuse. The program’s success has come quickly. As caseloads have grown, so too has Timap’s staff. The World Bank recently awarded the organization an $880,000 expansion grant. Maru surrounds himself with a community of fellow human rights activists and locals for company. Sierra Leone has a small Indian community, comprising mostly Sindhis, the majority of whom are shop owners. Maru says, “I haven’t really made a connection with them, although I am interested in their stories and how they ended up in Sierra Leone.”

Many of the younger Indian workers his age are almost indentured servants. “They are brought to Sierra Leone just to work, and once they get there, they are not free to move around. They just go from home to shop and shop to home, and they live in a very controlled, restrictive environment,” he explains. In fact, the most common interaction he has with them is when he is “pulled aside in the aisle and they ask me in a whisper if I have connections to get them out of Sierra Leone.” The plight of his fellow South Asians clearly bothers Maru. He loves the “pluralism” of cities like New York, for example, where people of all different backgrounds come together in cultural exchanges. But to him, Sierra Leone is fractured and the Indians “are not very connected to the rest of the country. There is a good deal of exploitation in the country and the Indians just exist on the periphery.” Because he values culture exchanges, Maru finds life in Sierra Leone difficult. Even though it has a rich tradition, its colonial, and more recent violent history, has left the country bereft of many pleasures, including art. “Life in Sierra Leone, for the most part, is hard,” he says, “and without much time to worry about retention of culture,” he explains. An avid dancer, he does make time to go out dancing with locals who still “really like to dance and enjoy life,” when they can, he says.

The arts are also close to Maru’s heart, because his alter ago is a Kutchi hip-hop artist; he regularly performs at benefits and cultural shows. His performances blend the Kutchi oral tradition and spoken word with hip-hop beats, complete with enviable dance moves. According to Maru, the Kutchi tradition is fragile. Stories are passed down orally from generation to generation. He is apprehensive the tradition might be lost by many of the children of Kutchi immigrants in America who are not exposed to this Gujarati oral form. His unique solution not only preserves this fragile art, but also gives the tradition relevance for many second generation South Asians in America. Maru’s ability to seamlessly blend this ancient tradition with modern hip-hop has brought attention and praise upon the Kutchi traditions he treasures from South Asians and non-South Asians alike. Maru is currently splitting his time between New York City and Sierra Leone as he ponders his future. Social ecology, education and perhaps human rights work in India are all on the table. But for now he is compelled to return to Sierra Leone, because, he says, “the feeling of making a tangible difference is addictive.” Fellow human rights lawyer and Timap board member Chi Mgbako explains the roots of Maru’s addiction. “Sierra Leone is one of the poorest, most desperate countries on earth, but through his work, Maru has planted a seed that is bearing fruit. He is proving to Sierra Leoneans that justice, something long denied to them, can be a lived reality in their everyday lives.” |