Magazine

An Ode to the Indian Diaspora

From Gladstone coolies to the plantations to computer code professionals in Silicon Valley, the Indian Diaspora has come of age as the educated, brainy tech Maharaja of the world.

|

The contemporary story of the rise of India is intertwined with the Indian Diaspora, which has played a vital role in the economic resurgence of the country.

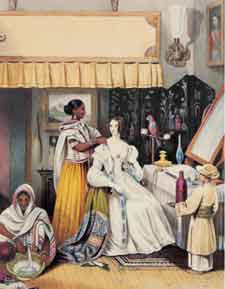

Though Indians had been venturing out to neighboring Asian countries since as early as the 1st century, the story of the Indian Diaspora primarily has its roots in the penal colony system of the late 18th century and the indentured labor system of the early 19th century. While the former involved the use of convicts as laborers in British South East Asia, the latter was started by would-be British premier Gladstone to supplant the needs of planters after black slavery was abolished in the early 19th century. The first ship that set sail from the Calcutta harbor in 1830s for the Bahamas, with a human cargo of 400 indentured laborers, is that blur, the opening fade in shot in history, when this great odyssey of the Indian Diaspora began. Between the 1830s and 1917, when the indentured system ended, nearly 1.5 million Indians were sold into debt-bondage. Some 240,000 were sent to British Guiana (now Guyana), 36,000 to Jamaica and nearly 144,000 to Trinidad. This “Desperate Diaspora” (to borrow a term from historian Brij Lal’s vocabulary) of close to a million Indians, driven by poverty and desperation and hoodwinked by colonial traders, sailed through Kala Paani (Black waters) to unknown regions to work, sleep, eat and work, without any hope of ever returning to the motherland. They are known as the Gladstone coolies.

This Diaspora was long forgotten, until writers like V S Naipaul began chronicling their stories in the 1960s in novels such A House for Mr. Biswas and The Mystic Masseur, both set in the Caribbean. They not only sought to write about the past, but also to renew their bonds with the motherland that had forsaken them. The initial results were searing narratives, such as Naipaul’s An Area of Darkness. In later years, Naipaul’s tradition was carried forward by writers such as Rohinton Mistry and M G Vassanji, among others. Meanwhile after independence, many of Indian doctors, engineers and scientists left for higher education and better job opportunities to North America, Europe, and Australia. Subsequently Indian laborers headed to the Gulf countries and South East Asia.

A new exodus of technically educated Indians to the great capitals of capitalism in the 1990s saw the emergence of what Lal calls the “Dollar Diaspora.” As the profile of Indian technology professionals, especially in the Silicon Valley grew, with many becoming leading high tech entrepreneurs, they transformed the image of Indians all over the world. After the dotcom bust, many technology professionals returned to India, almost 25,000 between 2001-2004, according the National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM), sparking India’s own economic boom. Indians became one of the forces to flatten the world, in Thomas Friedman’s famous turn of the phrase in the book The World is Flat. With the globalization of national economies, the chutnifaction of cultures and Bollywood’s increasing cultural appeal and reach, the new and old Diaspora began to both converge and diverge. Today, there is hardly a major country in the world that does not have an Indian community. From politics to business to cuisine to cinema and fashion, Indians and the Indian Diaspora have become a global force. In the United States alone, Indians are the most highly educated and affluent ethnic group. Chicken tikka masala has displaced fish and chips as the national dish in Britain. The Encyclopedia of the Indian Diaspora seeks to capture this world. Here you will discover Edward Peters from Goa, who sparked off the gold rush in New Zealand in 1853 though he never got credit for it. And that female Indian migrants are among the best-educated minority groups in most societies in the world.

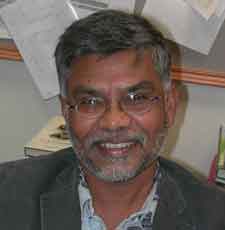

Professor Brij Lal of Australian National University, general editor of the volume, says the book recounts the “lived experiences” of Indian communities around the world. The encyclopaedia, produced at an estimated cost of $1.6 million, offers a panoramic insight into the movement and development of 44 Indian communities all over the world, through 30 thematic chapters, comprising over 350,000 words, 800 illustrations and 140 maps, tables and figures. Balaji Sadasivan, Singapore’s senior minister of state for foreign affairs, says, “The Indian Diaspora is increasingly perceived as an intrinsic part of the bigger story of humanity’s drift toward globalization, transnational economic and cultural flows, and hybrid forms of socio-cultural identity.”

Overseas Indians maintain a strong social, emotional and economic bond with the mother country. For example, the encyclopedia quotes a Guyanese girl Boodhia who has never been to India and probably never will, but nevertheless longs for the land of the Hindi movies she watches in a language she cannot understand. Or take the example of the proud Indian Mauritian who wept at the news of Indira Gandhi’s assassination as if he had lost someone in his own family. But the Indian diaspora is not just about emotion. Every year it remits billions of dollars to India – an estimated $23 billion in 2004. The idea of this hreference volume germinated at an academic workshop in 2001 and found considerable enthusiasm amongst many prominent Indians, including Singapore’s President Nathan. Lal is general editor of the encyclopaedia, which has entries from 60 scholars in 15 countries.

|

The Indian Diaspora has been growing in influence for some time now, so why wasn’t this phenomenon celebrated before?

The Indian Diaspora has been growing in influence for some time now, so why wasn’t this phenomenon celebrated before?